💡 TL;DR - The 30 Seconds Version

👉 85% of college students now use generative AI for coursework, but most schools lack clear policies on academic integrity and proper usage.

📊 Parent support for AI in schools dropped from 62% to 49% year-over-year, while nearly 70% oppose feeding student data into AI systems.

🏭 Microsoft, Google, and OpenAI committed billions to education AI programs, with the global market projected to grow from $6B to $32B by 2030.

🎓 Students want guidance over bans—97% seek institutional action on AI ethics through education and clear standards rather than enforcement.

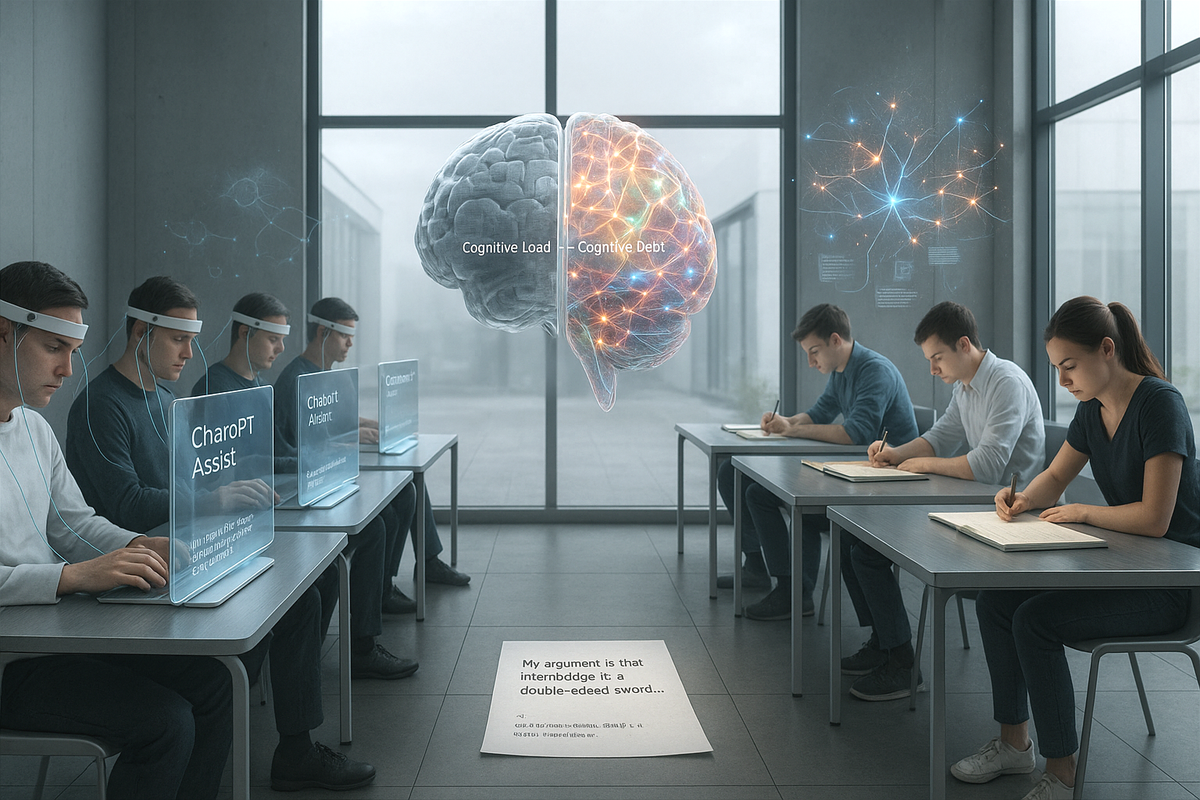

⚖️ The workforce preparation argument drives adoption, but evidence suggests AI exposure without critical thinking frameworks may undermine analytical skills.

🚀 As students outpace institutional policy development, tech companies increasingly shape educational standards and assessment criteria by default.

A majority of students now treat generative AI as a study partner, while institutions still debate rules—and companies rush to define them. In a July flash poll of 1,047 undergraduates across 166 U.S. campuses, 85% said they used AI for coursework, according to the Inside Higher Ed’s Student Voice survey.

Students adapt in days; policies take months; vendors move in hours. That’s the shift. It’s less about shiny tools than about who gets to set learning norms when schools can’t keep pace.

The numbers point both ways. Nearly all students (97%) want colleges to act on academic integrity in the AI era, but they prefer education and clear standards over policing. Meanwhile, parent trust in K-12 deployments is slipping, and spending on AI training and products is surging. Markets sense the vacuum.

Students are ahead—and conflicted

Most students use AI for scaffolding, not outsourcing: brainstorming (55%), tutor-style Q&A (50%), or studying for quizzes (46%). Only a quarter admit using it to complete assignments, and 19% to write full essays. That nuance matters.

Yet the cognitive trade-offs are real. Among recent users, 55% report “mixed” effects on learning and critical thinking; 27% say net positive; 7% net negative. Many want flexibility—paired with transparency and rules they can understand. They want guidance, not bans.

Community-college students lag in adoption and are more likely to report not using AI at all. That gap hints at an equity issue: access, time, and confidence shape how helpful these tools become.

Institutions stall; companies surge

Parents are cooling on AI in schools. Support for teachers using AI to draft lesson plans fell from 62% to 49% year over year. Nearly 70% oppose feeding student grades or personal data into AI systems. Trust is down, even as districts expand pilots.

In that hesitation, corporate frameworks have flourished. Microsoft, Google, and OpenAI now offer education-branded models, training, and toolkits. Nonprofits and “safe use” alliances amplify the pitch. District CIOs describe a familiar arc: early bans, vendor briefings, quiet reversals, and then selective rollouts that outpace faculty development.

The playbook is familiar.

The workforce frame is driving decisions

Leaders increasingly cite workforce readiness over pedagogy. If 40% of job skills will shift within five years, the argument goes, students must practice with AI now. Exposure becomes the deliverable; deep evaluation comes later.

That reframing changes incentives. The question shifts from “Does AI improve critical thinking?” to “Can we risk graduating students who haven’t used it?” Preparation is the new creed.

But a skills-first rush can backfire. Teachers report more integrity violations when students use tools without analytic guardrails. Students who can summon a passable draft in seconds often struggle to interrogate its sources, bias, or fit for purpose. Fluency without skepticism is a brittle competency.

Implementation gaps, messy realities

In practice, PD lags deployments. Many teachers spend only a few hours exploring tools all year, even as districts invest in corporate trainings that spotlight features over pedagogy. Classrooms experimenting with AI writing feedback show promise for struggling readers—until hallucinations and superficial paraphrases slip by unchecked.

And then there’s privacy. Some high-automation school models lean on aggressive data capture to “optimize” learning—webcams, on-screen tracking, and behavioral telemetry that would look at home in a call center. Guardrails remain thin.

The integrity problem students actually describe

Students say cheating stems from pressure: to get grades (37%), to save time (27%), or from disengagement with content. Few blame unclear policies (6%). Their fix is pragmatic: standardized, course-by-course rules; training on ethical use; assessments that measure understanding, not just output quality.

Translation: design work that AI can’t fake easily—oral defenses, in-class writing, iterative projects with personal context. Make expectations explicit. Then enforce them fairly.

A parallel K-12 shift complicates the picture

Districts are loosening AI bans even as more states adopt all-day phone restrictions. Teachers report calmer rooms and less distraction without phones, yet rollouts are uneven and costly. Parents worry about access and transparency. The net effect: a learning environment where one set of tools disappears while another, far less understood, moves in.

Where this leaves higher ed

Colleges can neither outsource governance to vendors nor pretend students will stop using AI. The credible path is narrower and slower: faculty-led standards, assignment redesign, targeted PD, and privacy guardrails that survive public scrutiny. That takes work. It also builds trust.

Students have been clear. Give them rules they can live with—and reasons that respect their reality.

Why this matters:

- Authority is shifting: As students adopt AI faster than institutions can write rules, companies step into the gap, shaping standards by default rather than by deliberation.

- Skills risk hollowing out: Workforce-first adoption without analytic guardrails can erode the very judgment and critical thinking that will differentiate graduates in an AI-saturated economy.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What specific AI tools are students actually using for schoolwork?

A: ChatGPT dominates student usage, followed by Google's Gemini and Claude. Students also use specialized education platforms like MagicSchool, which has grown to serve over 2 million students nationwide. Many access these tools through school-provided accounts rather than personal subscriptions.

Q: How much does it cost schools to implement AI programs?

A: Costs range from free basic access to several million annually for large districts. Yondr phone pouches cost $30 per student, while comprehensive AI training programs can run $250,000 per state. Colorado's statewide AI pilot used $3 million in federal pandemic relief funds.

Q: How do teachers detect when students are using AI inappropriately?

A: Most teachers rely on experience rather than detection software—only 21% of students support AI-detection tools. Teachers look for writing that doesn't match a student's usual style, generic responses, or factual errors typical of AI hallucinations. Many have shifted to in-class assignments and oral presentations.

Q: Which school districts have the clearest AI policies right now?

A: New York City, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia lead in structured rollouts. NYC allows teachers to use AI tools like Copilot by request, while LA plans middle school access for 2025-26. Most districts still lack comprehensive policies—the majority describe their approach as "pilots" or "under development."

Q: Are K-12 students using AI differently than college students?

A: Yes. College students primarily use AI for brainstorming and tutoring, while K-12 implementations focus more on teacher-guided activities. Community college students show lower adoption rates—21% report not using AI versus 14% at four-year schools, suggesting access and confidence gaps affect usage patterns.