Rene Haas has a word for the panic gripping tech stocks this week. "Micro-hysteria." The Arm CEO dropped it on an earnings call Wednesday night, hours after Anthropic's Cowork Legal tool had triggered a $285 billion software rout and chip stocks got dragged into the wreckage. Haas was sitting on record revenue for the fourth consecutive quarter. His stock dropped 8% anyway.

The reason, on paper, was a $15 million miss in licensing revenue. Five hundred and five million dollars against estimates of $520 million. A rounding error on a $1.24 billion quarter. But in a week where investors were selling first and thinking later, the miss gave them permission to dump the stock.

Forget the miss. Arm is not having a bad quarter. Arm is having the most important year in its 35-year history, and the evidence was scattered across that same earnings call, buried under the licensing headlines. Data center royalties doubled year-on-year. Neoverse CPUs crossed one billion cores deployed. Haas told analysts, plainly, that data center revenue would overtake smartphones within "a couple of years." If you've followed Arm since its IPO in 2023, you know that sentence rewrites the company's entire investment thesis.

The toll booth is moving

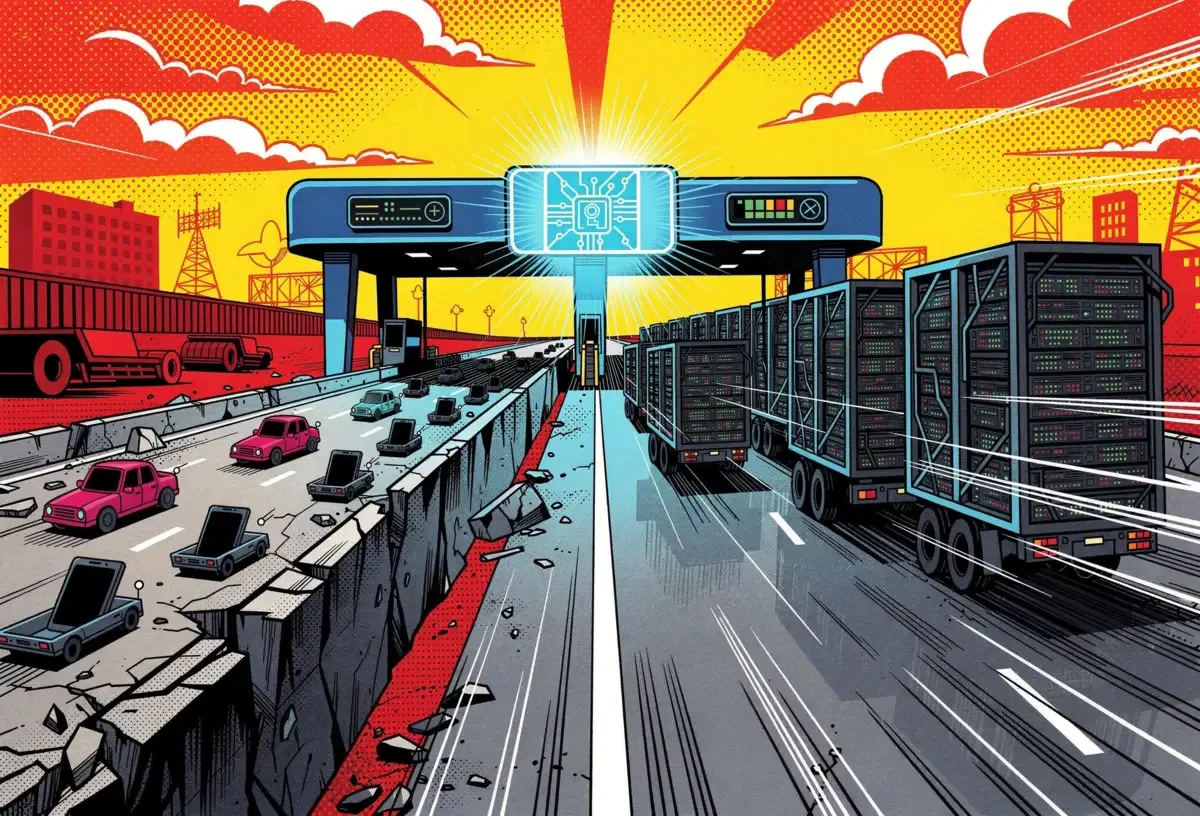

Arm's business model is deceptively simple. It designs chip blueprints. Other companies, from Apple to Nvidia to Qualcomm, pay for a license to use those blueprints. Then Arm collects a royalty on every chip shipped. A toll booth, basically, sitting on the highway between chip design and chip production.

The Argument

• Arm posted record Q3 revenue of $1.24 billion; stock fell 8% on a $15 million licensing miss

• Data center royalties doubled year-on-year; Neoverse CPUs crossed one billion cores deployed

• CEO Haas says data center revenue will overtake smartphones within two years

• Arm disclosed plans to build its own chip and scheduled a mystery March 24 event

For three decades, that toll booth sat squarely on the smartphone highway. Arm architecture powers roughly 99% of the world's mobile processors. The royalties were reliable, predictable, and growing slowly. Good business. Not exciting business.

What changed is AI. Not the chatbot-on-your-phone kind. The kind that needs thousands of CPUs running inference workloads in data centers, always on, burning through power budgets that would make a small city nervous. GPUs got the glory in the training phase. But inference, the part where AI models actually do things with new information, is a CPU story. And Arm's designs are the most power-efficient CPUs on the market.

Look at the royalty line. Arm's royalty revenue hit $737 million in the December quarter, up 27% and well above estimates. Data center royalties specifically doubled. AWS launched its fifth-generation Graviton processor with 192 Arm-based cores, double the previous generation. Nvidia's new Vera CPU runs 88 Arm cores. Microsoft's Cobalt 200 ships with 132.

Every one of those chips pays Arm a toll.

Why the licensing miss doesn't matter (and why it does)

Licensing revenue is the upfront fee companies pay to access Arm's designs. It's lumpy by nature, driven by when deals close rather than by underlying demand. A $15 million miss in a single quarter tells you almost nothing about the health of the business.

But here's why analysts got twitchy. Licensing today predicts royalties tomorrow. If fewer companies are signing up for new Arm designs now, the royalty stream could slow two or three years out. Summit Insights analyst Kinngai Chan put it bluntly on Wednesday. "A weak licensing revenue today will likely result in weaker future royalties revenue."

That logic sounds clean. It's also probably wrong in this case. Arm's licensing miss came during a quarter when the company signed two new Compute Subsystem licenses, bringing its total to 21 across 12 companies. Five customers are now shipping CSS-based chips. The top four Android smartphone vendors all ship Arm CSS devices. If you're looking for signs that customers are pulling back from Arm's designs, the licensing pipeline is not where you'll find them.

Join 10,000+ AI professionals

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The miss was a timing issue. Wall Street treated it as a thesis problem.

The inference economy needs a new chip

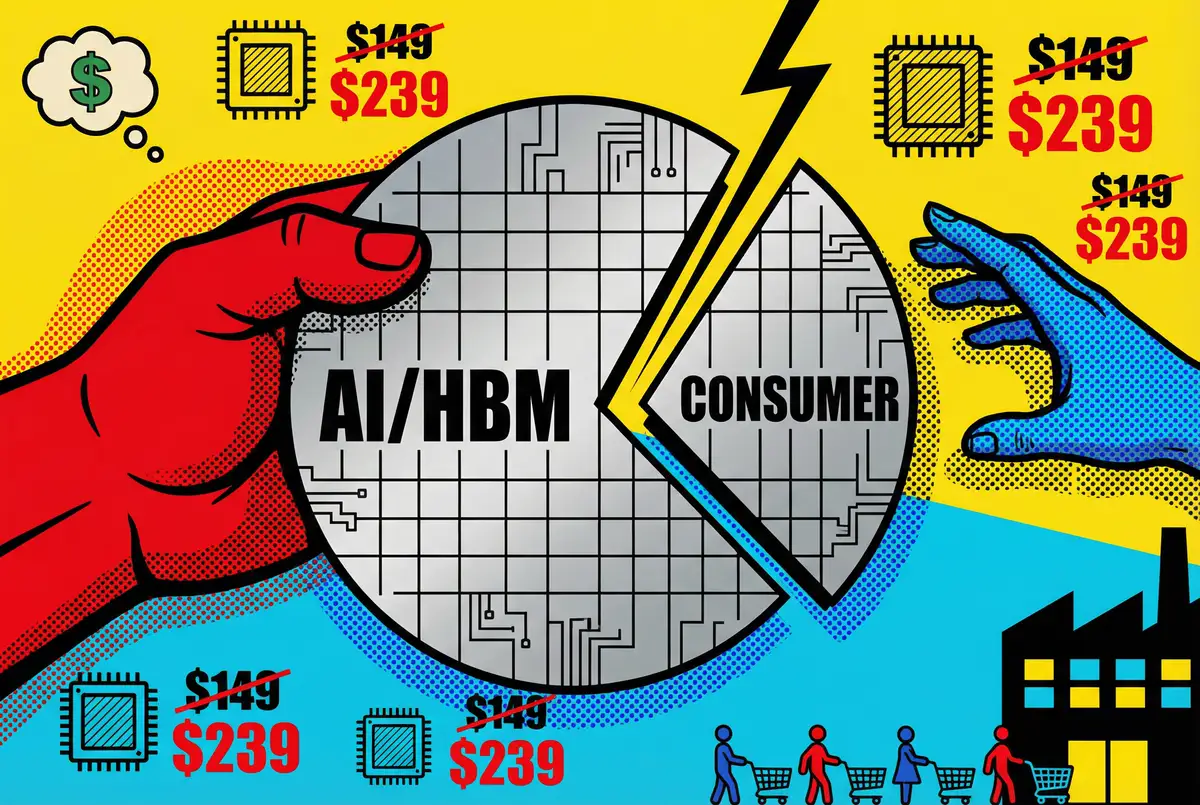

Something larger is shifting underneath the quarterly numbers. AI is moving from training to inference, and that changes who wins in the chip supply chain.

Training a large language model is a GPU-intensive brute-force exercise. You throw massive parallel compute at a dataset for weeks or months. Nvidia dominates this. Not even close.

Inference is a different animal. Walk into an AWS data center in Northern Virginia sometime. Rows of server racks, fans screaming, heat pouring off machines that never shut down. The AI agent reading your email and booking your flight lives in one of those racks. It needs a chip that stays on all day, sips power, and handles single-threaded tasks without choking. That's a CPU. Haas drove this point home on the call, noting that AI agents talking to other AI agents is "very, very well suited for CPUs because CPUs are very, very power efficient, always on, with very, very fast latency."

Arm's share among the top hyperscalers, AWS and Microsoft and Google, is approaching 50%. That number was close to zero five years ago. The company went from an afterthought in data centers to a coin flip against x86 in half a decade. And the trend is accelerating. More cores, every generation. More cores per chip means more royalty revenue per chip. The toll booth collects more every year, even before you count the expanding number of chips passing through it.

This is not speculative. It's already happening in Arm's financial results. The question is whether Wall Street can see past the quarterly noise long enough to price it in.

Smartphones are the floor, not the ceiling

Bears start with smartphones. They still account for roughly half the company's revenue, and the outlook there just got murkier. Qualcomm warned on Wednesday about a global memory shortage hitting mobile production volumes. Arm CFO Jason Child acknowledged the risk on the earnings call but framed it as manageable, estimating that even a 20% volume reduction would translate to a 2% to 4% hit on smartphone royalties.

That framing matters. Arm's smartphone business is mature, predictable, and relatively resilient to volume swings because the company earns higher royalties on premium chips. If phone makers cut production, they cut the low-end first, which is where Arm earns "dramatically smaller royalties," as Child put it.

And smartphones are increasingly an AI story too. On-device inference demands exactly the kind of power-efficient processing that Arm sells. The same architectural advantage driving data center adoption is reinforcing Arm's position in mobile.

The floor is solid. The growth is elsewhere.

And then there's the part Arm isn't talking about yet. Last summer, the company disclosed plans to build its own chip, not just license designs to others but compete alongside its own customers. It hired an Amazon AI executive to lead the effort. Operating expenses have climbed as a result. On Wednesday, Arm announced a March 24 event but executives refused to say what it was for. Read that silence however you want.

If Arm ships its own data center chip, the competitive math changes overnight. Intel and AMD, already losing hyperscaler share to Arm-based designs from their own customers, would face a direct competitor backed by the architecture that half the cloud already runs on. For Intel, which is bleeding server market share while restructuring its entire business, another front in the x86 war is the last thing the company needs.

Arm may never ship that chip. The licensing business is too profitable to risk alienating Apple and Nvidia. But the option matters. A company that owns the blueprints and collects tolls on every chip built from them has a choice its competitors don't. It can stay the toll booth. Or it can build the cars.

The market is pricing a miss when it should be pricing a transition

Arm's stock dropped 8% on a quarter where the company beat on revenue, beat on earnings, beat on royalties, guided above consensus, and had its CEO describe AI demand as "beyond no end in sight." The licensing miss was real. The reaction was not proportional.

Part of this is context. BofA analyst Vivek Arya noted "indiscriminate" selling in chip stocks before Arm even reported. JPMorgan's Toby Ogg wrote that software companies are now "sentenced before trial." Arm got caught in the crossfire of a market that's spooked by AI disruption and punishing anything adjacent to the hype.

But the irony is thick. Arm isn't being disrupted by AI. Arm is the company that designs the chips AI runs on. Every new AI agent, every inference workload, every data center expansion makes Arm's toll booth more valuable. The company is in the middle of the most consequential business model shift since it went public, moving from a smartphone royalty collector to the architecture that AI computing runs on.

Haas has set a measurable test. Data center revenue overtakes smartphones within a couple of years. Watch that number. If it crosses by fiscal 2028, the 8% selloff on a $15 million licensing miss will look like one of those moments where the market had the answer sheet and still failed the exam.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why did Arm's stock drop despite beating revenue estimates?

A: Licensing revenue came in at $505 million, about $15 million below Wall Street's $520 million estimate. In a week of broad tech selloffs triggered by Anthropic's Cowork Legal tool, investors used the miss as a reason to sell. The stock fell roughly 8% in after-hours trading.

Q: What is the difference between Arm's licensing and royalty revenue?

A: Licensing revenue is the upfront fee companies pay to access Arm's chip designs. Royalty revenue is the per-chip payment Arm collects every time a customer ships a product using its technology. Royalties are recurring and tied to volume; licensing is lumpy and tied to deal timing.

Q: How is AI inference changing demand for Arm chips?

A: AI inference workloads need CPUs that run continuously with low power consumption and fast response times. Arm's architecture is the most power-efficient option, and its share among top hyperscalers like AWS, Microsoft, and Google is approaching 50%, up from near zero five years ago.

Q: Could a global memory shortage hurt Arm's business?

A: Arm CFO Jason Child estimated that even a 20% reduction in smartphone volumes would only hit smartphone royalties by 2% to 4%. Memory shortages would mainly affect low-end devices, where Arm earns smaller royalties. Premium smartphones remain protected.

Q: Is Arm planning to build its own chips?

A: Arm disclosed plans last summer to build its own chip and hired an Amazon AI executive to lead the project. The company announced a March 24 event but refused to share details. If Arm ships a first-party data center chip, it would compete directly with Intel and AMD.