At CES 2026, the Central Hall told a story before anyone switched on a demo. TCL occupied the anchor position, 3,400 square meters of prime real estate where Samsung had planted its flag for two decades. Samsung retreated to a private suite at the Wynn, citing a more "intimate experience." The official explanation was strategic repositioning. The floor plan said something else.

The exhibition floor belonged to Chinese robots. One played table tennis against attendees. Another swept the carpet in slow loops. A third threw punches at a man who kept dodging left. Chinese companies ran 21 of the 38 booths showing human-form machines. Unitree's G1 drew crowds by backflipping from a standing start. AgiBot had a robot dancing near the main entrance, hips swaying to pop music. Booster Robotics lined up 30 units and ran them through synchronized steps. X-Humanoid sprinted its Tiangong Ultra across a short track. That machine won Beijing's humanoid half-marathon last year.

The American numbers? One hundred fifty units. That's Tesla's entire 2025 shipment. Figure AI moved the same quantity. Agility Robotics too. Add them up: 450 robots from the three leading US humanoid makers, into a global market of 13,318 units. AgiBot, one Chinese company, shipped 5,168.

Key Takeaways

• Chinese manufacturers shipped 13,318 humanoid robots in 2025. AgiBot alone (5,168 units) outsold all US companies combined by more than 10x.

• Component costs dropped from $280 to $28 as China built domestic supply chains. Morgan Stanley estimates Tesla's Optimus would cost 3x more without Chinese parts.

• Chinese companies occupied 21 of 38 humanoid robot booths at CES 2026. European industrial champions were largely absent from the category.

• The "ChatGPT moment" for robotics hasn't arrived. Most humanoid robots remain impressive demos unable to perform simple real-world tasks reliably.

The Numbers That Matter

Omdia dropped its annual humanoid robotics report during CES week. The findings tracked what the exhibition floor already showed. Global shipments jumped 480 percent over 2024. Chinese factories drove almost all of it.

AgiBot grabbed 39 percent of global volume. The Shanghai startup was founded by an engineer who left Huawei. Unitree, out of Hangzhou, captured 32 percent. That's 4,200 units. UBTech, listed in Hong Kong, landed third with a thousand. Leju Robotics, Engine AI, Fourier Intelligence rounded out the top six. Every one of them Chinese.

Where does that leave Tesla? Optimus, the robot Elon Musk keeps calling the company's long-term growth engine, took 1 percent of global shipments. Musk knows the pressure. He figures Tesla wins eventually. But he's also said the rest of the top ten could end up entirely Chinese.

Pricing tells part of the story. Unitree's entry model runs $6,000. AgiBot charges $14,000 for its compact version, still less than what most companies spend on a trade show booth. Tesla? Musk floated $20,000 to $30,000 for Optimus, but those units aren't shipping. Buy two Chinese humanoids today or wait for one American prototype. Not a hard call.

Price alone doesn't explain this, though. The gap runs deeper.

The Supply Chain Underneath

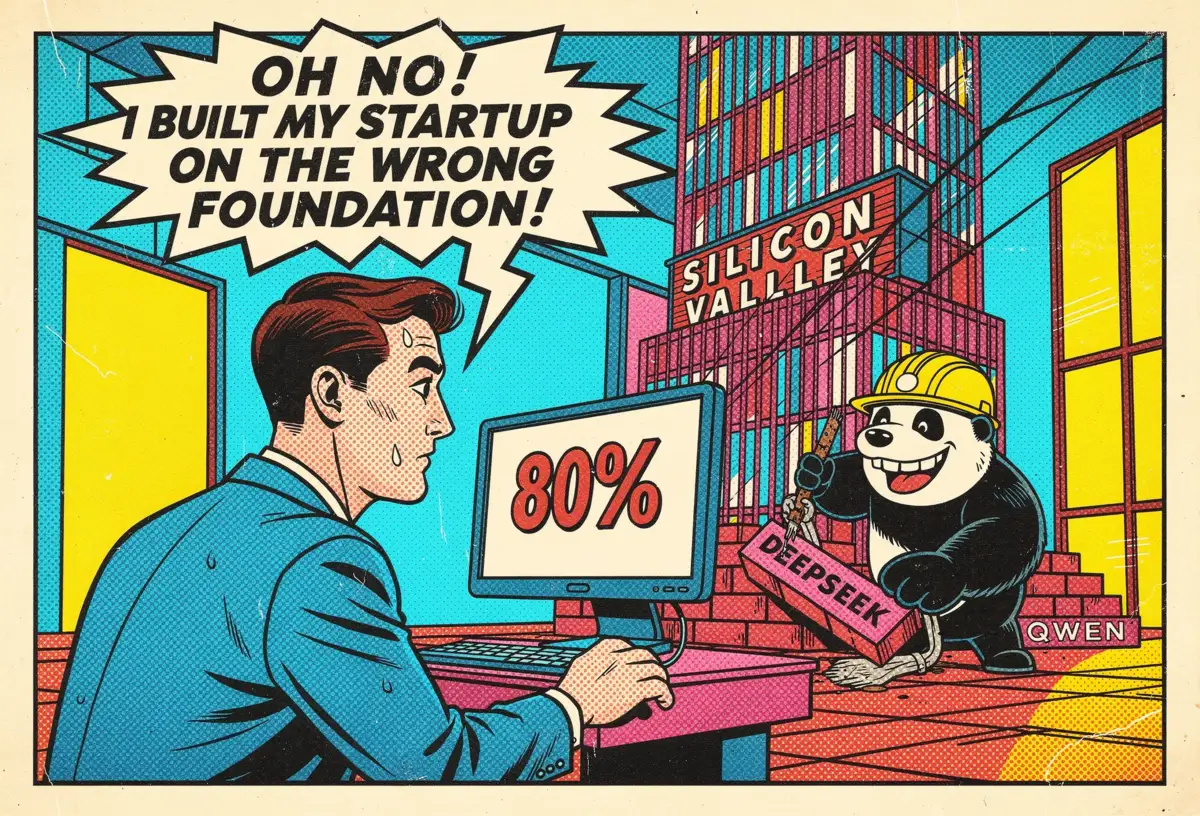

China didn't win by paying workers less. It won by building an entire parts industry while American robotics firms were still sketching form factors on whiteboards.

It's Lego versus sculpture. US companies treat each robot like a custom job, hunting for specialized components from suppliers scattered across three continents. China standardized the problem. Motors, gearboxes, sensors, all of it now comes off domestic lines.

Get Implicator.ai in your inbox

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Here's what that looks like in practice. Five years back, the actuators that move a humanoid's joints ran about $280 each when imported. Chinese factories now stamp out equivalent parts for $28. Not a 10 percent discount. A 90 percent collapse. Industrial policy plus factory scale equals a cost structure no one else can touch.

Morgan Stanley tried to model what Tesla's Optimus would cost if the company cut Chinese suppliers out entirely. The materials bill ballooned from around $46,000 to north of $130,000. Trace any American robot's supply chain back far enough and you land in Shenzhen. Washington doesn't enjoy that conversation.

Patents reinforce the picture. Chinese companies and universities filed 7,705 humanoid robotics patents over the past five years. American entities managed 1,561. That ratio doesn't reverse in a product cycle or two.

AgiBot hit a milestone in December 2025: five thousand humanoid robots shipped. The company runs a platform architecture. Same control software powers humanoids, wheeled robots, and four-legged machines. One brain, many bodies. Every deployment feeds training data back into the system. Development costs drop with each iteration.

Beijing designated "embodied intelligence" a strategic industry last March. Provincial governments started competing for robotics clusters. Training centers opened. Money poured in. By November, officials were warning about bubble risk. More than 150 humanoid robot companies now operate in China. The worry isn't whether capital will arrive. It's whether too much already has.

The Demo Problem

None of this means a humanoid robot can fold your shirts.

I watched a robot deal poker cards at CES. Each card took three seconds. The machine paused between deals like a nervous beginner trying to remember the rules. Nearby, another robot folded paper into pinwheels. Every crease required visible concentration, servos whining as fingers repositioned. Demo performance, not job performance.

"We await the ChatGPT moment of robotics," said Lei Yu, chief business officer at Galaxea Dynamics, a Beijing startup that raised $100 million last year. The company builds AI systems for humanoid makers and counts Stanford as a customer. Yu wasn't overselling. Chinese manufacturers are building for a market that doesn't fully exist yet.

Nadav Orbach runs RealSense, a company that supplies visual perception systems to 60 percent of humanoid robot makers worldwide. He put the problem plainly. "We want humanoids to respond to commands like 'get me a cold soda' and not an exhausting, 200-line set of instructions before fetching a drink. This is, to put it bluntly, very hard."

The hardware works. The brain lags. Today's humanoids walk, run, absorb shoves, flip backward. The physical engineering has arrived. What hasn't arrived: AI that handles open-ended reasoning the way a human does without thinking. Your six-year-old can rummage through an unfamiliar kitchen and find juice. A humanoid needs explicit code for every cabinet door, every fridge layout, every chair that might block the path.

Robert Playter at Boston Dynamics admitted the hype during CES week. His company already makes money, but mostly from quadruped robots doing industrial inspections. Humanoids remain a cost center, not a revenue line.

Esteban Kolsky, an analyst at Constellation Research, went harder. He called humanoids "the worst possible path we can take." Human bodies aren't efficient machines. We don't adapt well to unfamiliar spaces, and neither do robots built to mimic our proportions. Billions of dollars chasing a suboptimal blueprint.

That critique lands on technical grounds. It misses the commercial logic. Humanoids slot into factories designed for people. They use tools designed for hands. They walk through doorways sized for workers. The form factor is clunky, sure. But it fits existing infrastructure. Manufacturers who want automation without rebuilding their plants will pay for that compatibility. Elegance can wait.

Europe's Empty Chair

Eureka Park, the startup pavilion, has French founders pitching in one corner and German engineers demoing prototypes in another. Dutch teams cluster near the entrance. Europe shows up at CES. Just not in force.

France sent nearly 150 companies, most of them early-stage. Germany contributed 38 exhibitors. Italy brought 51. The Netherlands fielded 43. Grand total for the major European economies: around 300 companies.

China sent 942.

European presence concentrates in one hall and one phase of company growth. Startups looking for checks. Founders trading cards. Prototypes that might ship in eighteen months. What's missing? Scale. Industrial players who move thousands of units and set the specs everyone else follows.

For European delegates walking past booth after booth of Chinese robots, the feeling wasn't competition. It was erasure. Europe has car giants. It has precision manufacturing. It has decades of factory automation expertise. Bosch came to CES, but as a partner to Chinese EV makers. Not as a humanoid competitor. Volkswagen scaled back. BMW too. The continent that once defined industrial robotics has mostly walked away from the humanoid category.

Part of this makes financial sense. A serious CES booth costs millions. Trade shows in Munich and Barcelona draw specialized audiences closer to home. But skipping Las Vegas carries consequences. CES sets the expectations. It decides what counts as progress. If you're not on the floor, you're not in the conversation.

Brussels loves the phrase "digital sovereignty." It shows up in white papers, ministerial speeches, strategy decks. Everyone nods. On the CES floor, that rhetoric cashes out as a startup pavilion and a notable gap where Siemens or Bosch might have stood with actual humanoid competitors.

The Brain and the Body

American companies own the models. ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, the large language systems that define the current AI moment, all run on American architectures trained on American chips. Nvidia's keynote pulled the largest crowd of the week. Jensen Huang stood on stage next to a row of robots and declared his company the engine of physical AI.

Nvidia doesn't build robots. It builds the processors robots run on. The distinction matters more than Huang's stage design implied. The value chain is forking. American firms dominate compute. Chinese firms dominate the physical layer. Software versus hardware. The brain and the body, split across an ocean.

Both halves matter. A foundation model without a robot is a chatbot. A robot without capable AI is an overpriced mannequin. The question is who gets to integrate them, and on whose platform.

Daily at 6am PST

The AI news your competitors read first

No breathless headlines. No "everything is changing" filler. Just who moved, what broke, and why it matters.

Free. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Arm Holdings, the British chip design house that SoftBank owns and New York lists, announced a restructuring at CES. A new "Physical AI" division now combines automotive and robotics. The logic: cars and robots share requirements. Low latency, tight thermal limits, sensor fusion, safety certification. Arm wants to be the architecture underneath all of it.

The bet assumes physical AI becomes a real market, large enough to offset stalling smartphone growth. Arm's model depends on volume. If humanoid shipments stay niche, the division stays small. CES demos don't generate licensing fees.

The Capital Shift

American venture capital used to pour into Chinese tech companies. That pipeline closed. Regulatory pressure, geopolitical friction, outright bans on certain sectors.

Beijing filled the gap. Late December 2025, the central government launched a $138 billion fund aimed at "hard technologies": robotics, chips, aerospace. Twenty-year time horizon. American VCs work on seven-year cycles. The patience mismatch is structural.

Sovereign wealth funds from the Gulf have stepped in too. UAE and Saudi investors see Chinese robotics as part of their smart city ambitions. Money that once flowed from Sand Hill Road to Shenzhen now arrives from Abu Dhabi instead. Different letterhead, same destination.

Chinese robotics startups posted record raises in 2025. X Square Robot closed $100 million with Alibaba leading. Galaxy Bot pulled in $154 million. Fourier raised $109 million. Crunchbase figures show more than $6 billion went into robotics globally last year. A big share landed in China.

Pulling American money out didn't starve the sector. It rerouted the capital and removed the Silicon Valley veto.

What Gets Built

On the CES floor, American executives pitched timelines. Chinese companies shipped units. Both sides invoked AI. Only one side had volume behind the words.

This isn't victory for China. Not yet. The gap between trade-show demo and factory deployment hasn't closed. Robots that generate positive ROI remain rare. Most humanoids today work inside controlled perimeters, running rehearsed sequences for crowds that expect glitches.

But the scaffolding is up. Factories. Supply chains. Capital pipelines. Patent portfolios. When humanoid robots actually become useful, Chinese companies will be ready to build them faster and cheaper than anyone.

Jensen Huang called it the "ChatGPT moment" of physical AI. Wishful framing. ChatGPT worked well enough, immediately, for tasks people actually wanted done. Humanoid robots don't clear that bar. They dazzle at conventions and stumble in kitchens.

The real question isn't whether physical AI arrives. It's whether American companies will have production capacity when it does. China spent a decade building the factories, training the workers, and collapsing the costs. Export controls and tariff walls don't erase that foundation.

At CES 2026, the robots danced. The demos drew crowds. TCL owned the Central Hall. And somewhere in the Wynn, Samsung executives explained why a private suite better served their strategic vision.

The floor plan told the truth.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why can't American companies just build their own robotics supply chain?

A: Cost and time. Morgan Stanley estimates Tesla's Optimus would cost $131,000 instead of $46,000 without Chinese suppliers. That's nearly triple. China spent a decade building factories, training workers, and scaling production. Replicating that infrastructure in the US would take years and billions in investment, with no guarantee of matching Chinese prices.

Q: Where is the money coming from now that US venture capital has pulled out of China?

A: Two sources. Beijing launched a $138 billion state fund in December 2025 targeting robotics, semiconductors, and aerospace with a 20-year horizon. Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds from the UAE and Saudi Arabia have also entered, viewing Chinese robotics as aligned with their smart city ambitions. The funding pipeline shifted, but didn't shrink.

Q: Why build humanoid robots when other designs might be more efficient?

A: Compatibility. Humanoid robots fit into spaces built for humans and can use existing tools without factory redesigns. A warehouse built for human workers doesn't need new doorways, workstations, or equipment for a humanoid. The form factor is mechanically inefficient but commercially practical for companies that want automation without reconstruction.

Q: Who is actually buying these humanoid robots right now?

A: Research institutions, universities, and industrial pilot programs. AgiBot secured an order for nearly 100 robots from auto parts manufacturer Fulin Precision in August 2025. Galaxea Dynamics counts Stanford among its customers. Most buyers are testing capabilities and collecting training data, not deploying robots for production work. Commercial returns remain limited.

Q: What happened to European robotics companies?

A: They're present but not competing. Bosch attended CES 2026 as a partner to Chinese EV makers, not as a humanoid robotics competitor. Volkswagen and BMW scaled back participation. Europe sent roughly 300 exhibitors versus China's 942, and most European companies were early-stage startups, not industrial players shipping at scale. The continent has ceded the humanoid category.