💡 TL;DR - The 30 Seconds Version

⚖️ Arizona judge called AI deadbot victim statement "genuine" and imposed maximum 10.5-year sentence on killer in May.

💰 Digital afterlife industry projected to hit $80 billion within a decade as companies test ad-supported deadbot models.

🏭 Executives already field-testing interstitial ads and data harvesting through intimate conversations with deceased avatars.

📱 No federal AI replica laws exist—only patchwork state publicity rights create legal confusion for liability chains.

🎭 Americans accepted digital resurrections before (Fred Astaire vacuum ads) and ads on streaming—pattern suggests normalization ahead.

🚨 Each "acceptable" advocacy use makes commercial exploitation easier to justify as emotional manipulation enters private grief.

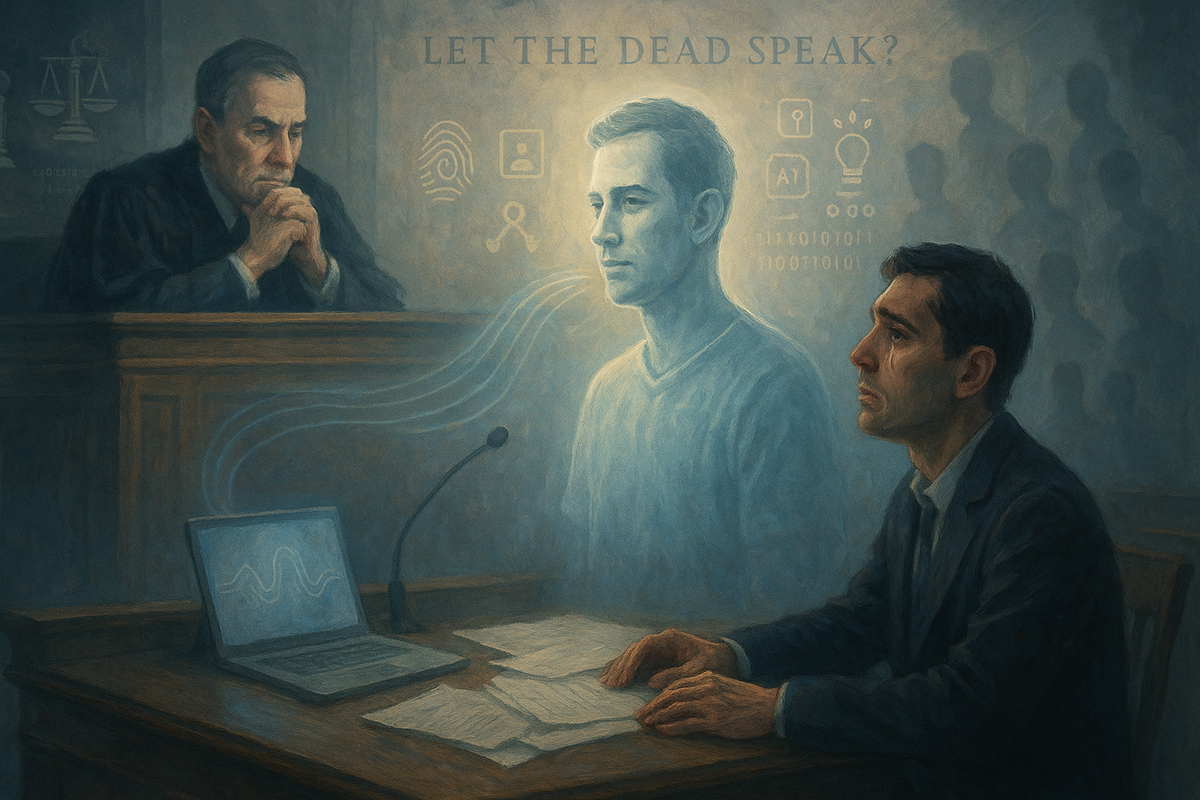

A murder victim’s AI avatar just helped send his killer to prison; marketers now see the same technology as ad real estate while U.S. law lags behind according to a report by NPR.

In May, an Arizona courtroom played a video of Chris Pelkey, a 37-year-old veteran killed in a 2021 road-rage incident. It was an AI “deadbot,” built by his family, speaking in his likeness. Judge Todd Lang called the message “genuine” and sentenced the defendant to 10.5 years—the statutory maximum for the charge. That moment cemented deadbots as tools of persuasion, not just memorials. The commercial implications are obvious.

In August, a beanie-wearing avatar of Parkland victim Joaquin “Guac” Oliver answered questions from journalist Jim Acosta. The point was advocacy, not entertainment. Still, you could feel the format’s reach. It lands.

What’s actually new

Deadbots are shifting from text to rich video and voice. The leap matters. As cartoonist and author Amy Kurzweil notes, moving from grainy text to lifelike avatars turns remembrance into something closer to a 3D encounter. Higher fidelity amplifies emotion—and persuasion. That’s the core update.

The market is moving too. The “digital afterlife” sector—everything from legacy tools to AI memorials—is projected to quadruple to nearly $80 billion within a decade. The money chases immersion. It will.

Evidence of a pivot to monetization

Industry researchers say commercialization is not hypothetical. “Of course it will be monetized,” argues Lindenwood University’s James Hutson, who has studied the ethics of AI reanimations. His caution echoes a broader academic drumbeat: as realism improves, so does the incentive to capture attention, harvest data, and sell access to intimate moments.

Executives are already field-testing “ad-friendly” patterns. Think interstitial spots that interrupt a conversation with a deadbot. Or avatars that casually ask about favorites—teams, brands, jerseys—and pass those signals to a marketing stack. The pitch isn’t necessarily, “Grandma endorses detergent.” It’s, “Grandma keeps you engaged long enough to learn what to sell you.” Chilling.

The commercial playbook, in plain terms

Three forces line up. Deadbots hold attention longer than static memorials because they respond, creating premium inventory. The perceived intimacy builds trust and lowers defenses, so soft asks feel less like targeting. And conversations generate first-party signals that advertisers can’t easily get elsewhere.

Advertisers have followed grief, love, and nostalgia into every medium that could be measured—radio, TV, social, DMs. Deadbots are the next interface. Expect A/B tests before guardrails, not after. That’s how adtech rolls.

Law and liability can’t keep pace

There’s no comprehensive U.S. federal framework for AI replicas. Instead, a patchwork of state publicity and “digital replica” laws governs use of a person’s name, likeness, and voice—sometimes post-mortem, sometimes not, with durations and exceptions that vary widely. The result is predictable: forum-shopping and confusion about who’s on the hook when a deadbot crosses a line.

The liability chain is knotted. Is it the platform that built the avatar? The ad network that placed the spot? The brand that funded it? Or the estate that authorized (or failed to police) the use? Even courts willing to admit a victim’s AI statement for sentencing are unlikely to bless commercial messages from the dead without clearer standards. Not yet.

Normalization is the tell

Americans have already accepted digital resurrections in ads—remember Fred Astaire hawking vacuum cleaners in the 1990s. Consumers also swallowed ads inside paid streaming tiers they once swore they’d never tolerate. The pattern is familiar: novelty, backlash, habituation, revenue. Deadbots simply raise the emotional stakes.

Advocacy deployments accelerate this normalization. Pelkey’s video was embraced as restorative justice. The Oliver interview pushed policy into living rooms. Each “acceptable” use makes the next one easier to justify. That’s how edge cases become defaults. Quickly.

Limitations and failure modes

Deadbots can misrepresent the deceased, even with family consent. Scripts reflect survivors’ interpretations, not necessarily the person’s words. Lifelike voices and faces intensify the risk of manipulation—of judges, jurors, or grieving relatives. And because intimacy is the product, data security is not a nice-to-have. It’s existential. One breach of “conversations with mom” would poison the well.

Regulators face a hard trade-off: preserve expressive and memorial uses without opening a lane for predatory ads. Without baseline disclosure, consent, audit logs, and bright-line bans on covert targeting, the industry will run faster than the rules. It always does.

Why this matters:

- Interactive replicas move persuasion into private grief, where defenses are lowest and consent is murkiest.

- Once courts, media, and families normalize deadbots, ad-funded models will follow unless guardrails arrive first.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How much does it cost to create a deadbot?

A: Current companies like StoryFile and Hereafter charge through subscription models or upfront fees, but exact pricing isn't publicly disclosed. The article notes this will likely shift to ad-supported models as the market matures, similar to how streaming services introduced advertising tiers.

Q: What legal protections exist for deceased people's digital likenesses?

A: Only state-level publicity rights laws that vary widely in duration and scope. Some states protect name, likeness, and voice after death, others don't. There's no federal framework, creating legal confusion about liability when deadbots cross state lines or cause harm.

Q: How realistic are current deadbots compared to the original person?

A: The technology has evolved from text-based chatbots to voice and video avatars. Quality depends on source material available—archived recordings, photos, and writing samples. The Chris Pelkey and Joaquin Oliver cases used family-created avatars that convinced courts and media of their authenticity.

Q: Are any companies already running deadbot advertisements?

A: Not directly. Companies are currently "testing internally" according to StoryFile's CEO, but no deadbot ads are publicly running. However, digital resurrections aren't new—Fred Astaire appeared in Dirt Devil commercials in the 1990s, suggesting precedent for deceased celebrity endorsements.

Q: What personal data can deadbots collect during conversations?

A: Deadbots can probe for consumer preferences like favorite teams, brands, or products during seemingly innocent conversations. This first-party data is valuable to advertisers because it comes from intimate, low-defense interactions that traditional advertising can't access. The emotional context makes users more likely to share personal information.