💡 TL;DR - The 30 Seconds Version

👉 Chinese firm Geedge Networks sells turnkey surveillance systems to Pakistan, Myanmar, Kazakhstan, and Ethiopia using technology originally built by US companies like IBM.

📊 Myanmar's system monitors 81 million internet connections simultaneously while Pakistan can tap 4 million mobile phones in real-time through these exported tools.

🏭 The technology traces back to IBM's work building China's "Golden Shield" policing system in 2009, later refined during the Xinjiang crackdown.

🌍 Multinational supply chains spread legal risk across US, French, German, and UAE companies, making export controls increasingly ineffective against modular systems.

🚀 Overseas deployments create a feedback loop, with lessons learned abroad improving domestic Chinese surveillance through software updates and new features.

🎯 Geedge is hiring engineers for Belt and Road deployments across Asia and Africa as demand grows for "control-tech-as-a-service" solutions.

Digital authoritarianism didn’t just spread. It was productized—and now it ships worldwide.

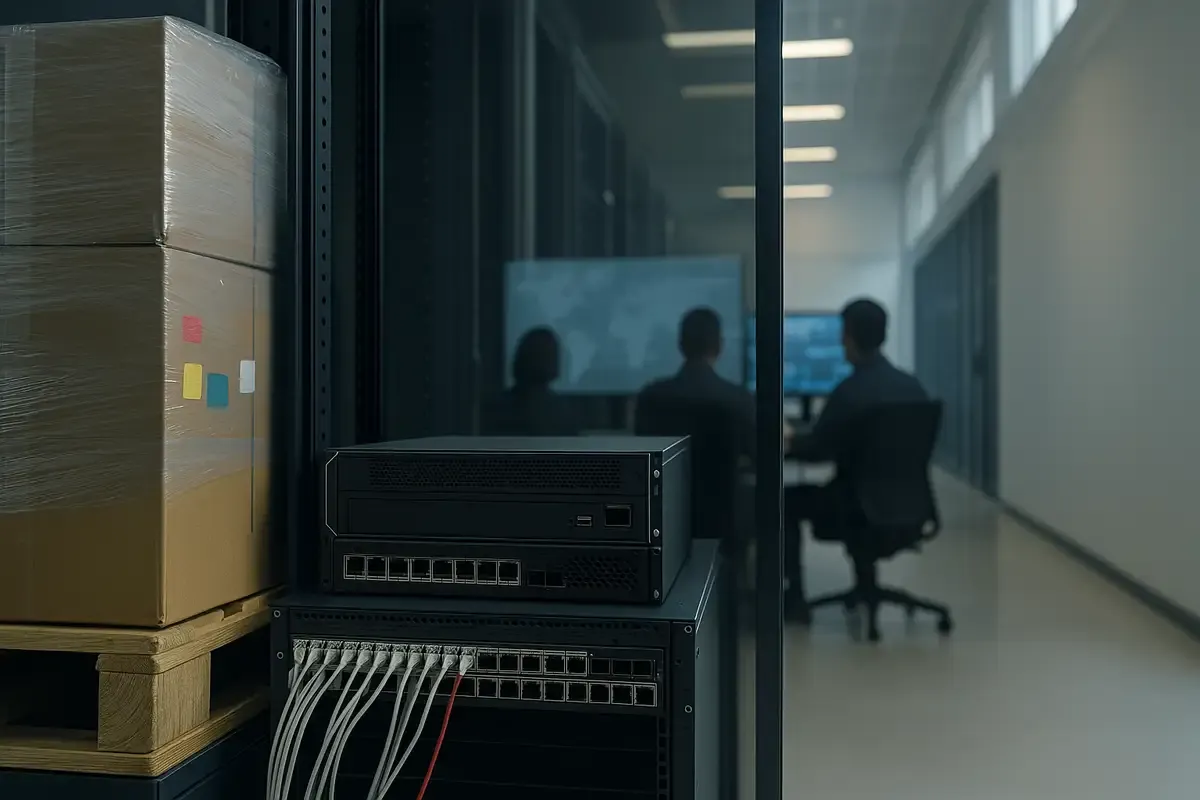

China’s state surveillance no longer looks like bespoke engineering overseen by security services. It looks like a commercial stack. A leak this week details how Geedge Networks, a little-known Chinese firm with ties to the architect of the Great Firewall, is selling turnkey censorship and monitoring systems to Pakistan, Myanmar, Kazakhstan, and Ethiopia. The blueprint traces back to U.S. tech: an Associated Press investigation found American companies helped design and supply the core of China’s policing infrastructure in the 2000s, which was later refined during the Xinjiang crackdown and is now exported as a service. The arc is stark. The claim was “neutral tech.” The result is a global market for control.

How the blueprint was drawn

American companies did not merely sell general-purpose servers and switches into China. They pitched policing. Classified plans reviewed by reporters show IBM worked with the state defense contractor Huadi on Phase Two of “Golden Shield,” China’s national police IT program, to fuse data streams and enable predictive policing intended to “maintain stability.” Oracle databases, Cisco networking, and accelerators from Intel and Nvidia rounded out the stack. These were not abstract capabilities. Marketing materials used official catchphrases like “key persons” and “abnormal gatherings.” The intention was explicit.

Xinjiang became the crucible. IBM’s i2 analysis software, resold by the Chinese firm Landasoft, informed the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), which aggregated travel records, communications, biometrics, and religious markers to assign risk scores. In one documented week in 2017, the IJOP flagged more than 24,000 “suspicious” people, many of whom were detained. The program’s basic premise—detain first, justify later—was administrative, automated, and brutally efficient. It worked because the underlying systems interoperated. That was the selling point.

Companies say they followed export laws, cut ties when concerns arose, or never knowingly sold to police in sensitive regions. Those statements matter. So do outcomes.

From bespoke builds to SKUs

By 2018, Chinese vendors had learned enough to package the model. Geedge Networks emerged with a catalog approach: gateway hardware for deep inspection at carrier scale and a browser-based console non-technical officials could use to monitor entire populations. In Myanmar, internal screenshots show the system watching 81 million concurrent connections. Within months, engineers moved from sporadic blocking of circumvention tools to highly effective VPN suppression, aided by curated blocklists and machine-learning classifiers. It’s point-and-click repression. Fast.

Pakistan illustrates the end-to-end version. The country’s Web Monitoring System 2.0 can block two million active sessions at once and throttle platforms across the network. In parallel, a Lawful Intercept Management System allows at least four million mobile phones to be tapped concurrently. Licensing files and logs show operators can view email contents, attachments, and metadata where encryption is absent, and can still track destinations when it isn’t. The effect is ambient self-censorship. People go quiet. So do their contacts.

This is not theoretical. It’s operational.

A multinational supply chain for control

Look under the hood and you won’t find a single country’s kit. You’ll find a procurement puzzle. After Canada-based Sandvine withdrew gear from Pakistan, Geedge adapted to the hardware left behind, swapping in its own software and Chinese-made components while slotting in modules from firms in the United States, France, Germany, and the United Arab Emirates. In practice, interception, policy enforcement, storage, and visualization come from different vendors, often in different jurisdictions.

That modularity is a feature, not a bug. It spreads legal risk, confuses oversight, and keeps projects moving if any one supplier faces sanctions. It also gives buyers plausible deniability: they can say they purchased “traffic engineering” or “threat intelligence,” not censorship. Everyone is a sub-contractor. Responsibility is diluted by design.

Geedge’s hiring plans reinforce the strategy. The firm is recruiting engineers for “Belt and Road” deployments, Spanish- and French-speaking support staff, and long-stint field roles across South and Southeast Asia, North Africa, and the Gulf. This is standard enterprise go-to-market, repurposed for sovereignty control tech. Scale is the objective.

The closed loop back to China

Export isn’t the end of the story. It’s a feedback channel. Leaked materials show Geedge running pilots in Xinjiang, Fujian, and Jiangsu that ingest the lessons from overseas and test new functions at home: graphing social relationships, triangulating user locations via cell towers, and enforcing geofenced “deny lists.” One prototype assigns every user an internet “reputation” score starting at 550; those who fail to rise above 600 through verified identity and employment may lose access entirely. That is not content moderation. It is credentialed connectivity.

Features validated abroad can be rolled back into domestic builds with a software update. The loop tightens. So does the control.

Export controls meet a kit economy

Regulators face a moving target. After 2019, tighter U.S. controls slowed some direct sales into China, and several companies say they ended sensitive contracts or barred sales in Xinjiang and Tibet years earlier. But the market evolved. Today’s systems are assembled from generic compute, off-the-shelf interception gear, and cloud-style software that is easy to rebrand and relocate. When one supplier exits, another integrates. When hardware is left behind, it is repurposed. Sanctions built for finished products struggle against an industry that sells building blocks.

The result is a service model for repression. It is priced, supported, and upgradeable. It travels well.

What happens next

Three forces will keep pushing this forward. First, demand: governments facing unrest or instability will always buy tools that promise control. Second, supply: the stack has matured into repeatable deployments that don’t require deep local expertise. Third, data: every new rollout yields operational telemetry that improves classifiers and workflows, justifying the next sale and the next budget cycle. It compounds. Quietly.

The marketing euphemism is “urban safety.” The reality is population management.

Why this matters

- An industrialized surveillance stack—born in joint U.S.–China projects, refined in Xinjiang—now ships as “control-tech-as-a-service” to governments worldwide, diffusing accountability across borders.

- Export controls aimed at single vendors or finished products are mismatched to a modular, multinational supply chain that can reassemble the same capabilities from interchangeable parts.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What exactly can these surveillance systems see about individual users?

A: The systems intercept phone calls, text messages, email content and attachments, plus track which websites people visit. For encrypted traffic, they can still see metadata like destinations and timing. Pakistan's system can monitor 4 million phones simultaneously and view full email contents when unencrypted.

Q: How much do countries pay for these surveillance systems?

A: Costs aren't publicly disclosed, but leaked documents show China spent $37,000 just to monitor one family's "abnormal petitioning." The systems require hardware installations across dozens of data centers plus ongoing software licensing and maintenance contracts with multiple international suppliers.

Q: Can people still use VPNs to bypass this surveillance?

A: Increasingly difficult. In Myanmar, Geedge identified 281 VPN tools for blocking and went from failing to block most VPNs to blocking nearly all within months using machine learning. The systems use deep packet inspection to detect and block circumvention tools in real-time.

Q: Which countries might adopt these systems next?

A: Geedge is actively hiring engineers for deployments in Malaysia, Bahrain, Algeria, and India, plus Spanish and French translators for overseas work. The company targets "Belt and Road" countries within China's economic influence, suggesting expansion across Asia, Africa, and potentially Latin America.

Q: How does this compare to surveillance in the US or Europe?

A: Western surveillance typically requires warrants for individual targets and focuses on specific threats. These systems monitor entire populations by default—Pakistan can tap 4 million phones simultaneously without individual justification. The scale and automation are fundamentally different from targeted law enforcement surveillance.