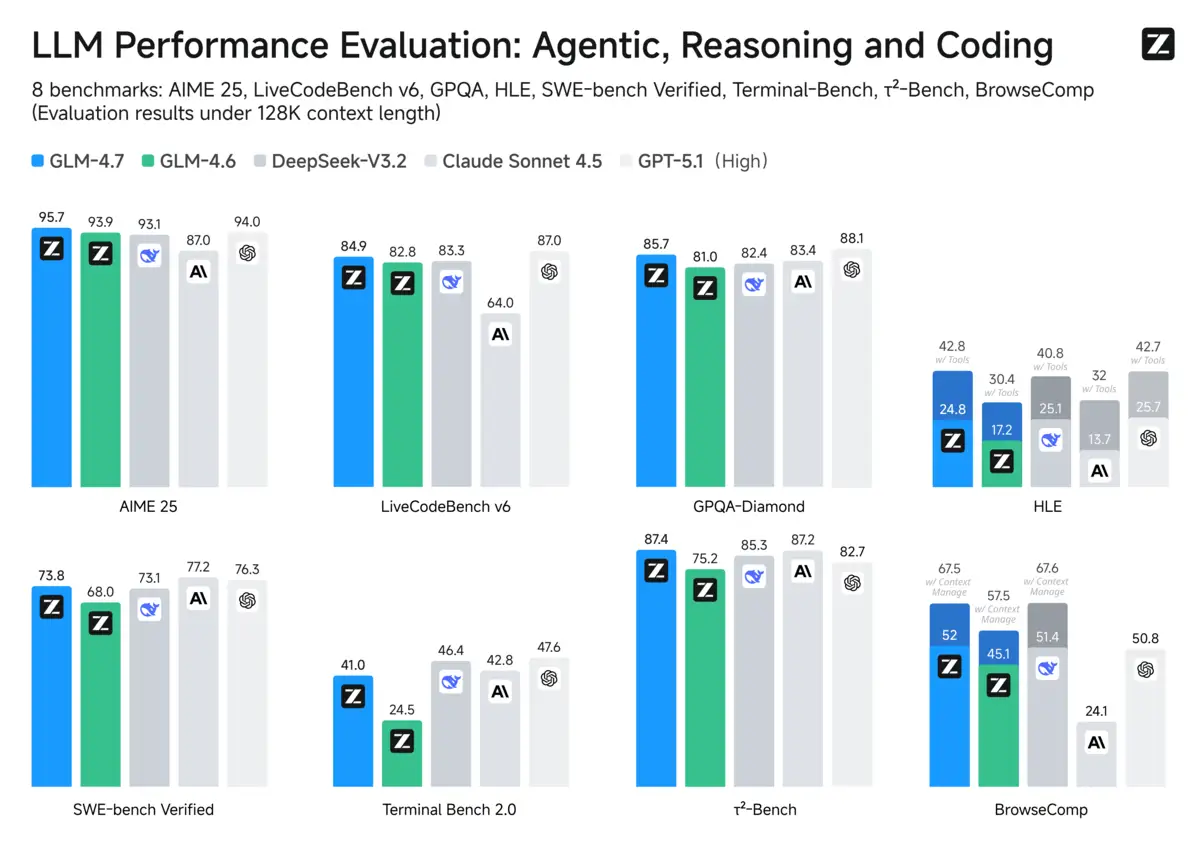

If you only look at Zhipu AI's launch chart for GLM-4.7, you come away with a simple impression: here's a Chinese coding model trading blows with the best in the West.

That impression is doing a lot of work.

The chart compares GLM-4.7 against a tidy lineup: its predecessor, a domestic rival, and two familiar Western names. What it doesn't show is Gemini 3.0 Pro. And in the fine print, Zhipu's own table makes clear why that omission matters: on several of the same coding and agentic evaluations, Google's model comes out ahead.

But the more interesting signal in this release isn't the missing bar. It's the price tag.

Zhipu is offering access at roughly €30 a year, a figure so low it changes the conversation. This isn't just a model claiming capability. It's a model making a bid to become the cheapest engine swap inside tools developers already use.

GLM-4.7 reads less like a moonshot and more like a playbook: shape the first impression, compress the cost base, claim openness without giving away the business, and plug into your competitor's distribution. In 2025's AI market, that combination matters as much as any single benchmark score.

The Breakdown

• Zhipu's benchmark chart excludes Gemini 3.0 Pro, which leads GLM-4.7 on several key evaluations in the company's own data table

• At €30/year, GLM-4.7 is priced to become a cheap engine swap inside Western agentic coding tools like Claude Code

• Open weights require ~$10,000 in hardware to run practically, channeling most real usage toward paid API endpoints

• The model was explicitly optimized for Claude Code compatibility, turning competitor tooling into distribution infrastructure

How the chart tells one story

Zhipu's benchmark graphic is doing what benchmark graphics usually do: it tells a clean story at a glance. The problem is that the clean story depends on the cast of characters. Gemini isn't in the visualization, even though it appears in the accompanying table, and the table complicates the "frontier-competitive" impression considerably.

The same selective framing shows up in the OpenAI comparison. The release includes GPT-5 and GPT-5.1 High, but not GPT-5.2, which had already landed by the time this launch cycle was underway. A reasonable interpretation, raised by commenters watching the release cadence, is that the evaluation window simply froze at a convenient point. Rerunning a full suite every time a competitor ships isn't practical.

That explanation is understandable. It's also the point.

In fast-moving model markets, the truth most people internalize is the one rendered as a chart. The table is where nuance goes to wait for readers who still have the patience to scroll.

GLM-4.7 does improve meaningfully over GLM-4.6 on coding-relevant measures. That's real progress. Developers who tried the previous version and bounced may try again, because the gap is no longer embarrassing. The more controversial claim, the one implied by the chart's presentation, is that GLM-4.7 is now a peer to the leading Western frontier models. The table, read as a whole, paints a messier picture: competitive in places, behind in others, and clearly advantaged in Chinese-language tasks.

That last part matters. GLM-4.7's strength on Chinese web and browsing evaluations isn't mysterious. It's what you'd expect from training exposure and data distribution. Where Western labs have blind spots, domestic labs can look unusually sharp.

The real competition is cost, not capability

Benchmarks argue about capability. Pricing argues about economics.

A €30 annual plan isn't a normal commercial decision for a model being positioned against products that cost serious money per month. It's a wedge. It's a way of asking developers a very specific question: if you can get good-enough coding performance inside your existing workflow for a fraction of the cost, why keep paying for the premium engine?

That's the arbitrage at the center of this launch. Western labs have spent years and vast compute budgets pushing the frontier forward. If a competitor can get close enough, close enough for most day-to-day coding tasks, then the market becomes less about who is best and more about who is cheap enough to substitute.

This is where provenance talk starts to appear, because the incentive is obvious. If you can reduce training cost by leaning on synthetic data and model-generated outputs, you're not just competing on research. You're competing on someone else's amortized R&D.

Developers watching GLM-4.7 have reported stylistic echoes that trigger exactly that suspicion: reasoning-format outputs that resemble Gemini's layout, occasional Claude-like verbal patterns when the model runs through Claude-adjacent tooling. None of that is proof of anything by itself. Formatting converges, prompts leak patterns, and tooling can impose structure. But it's enough to keep the provenance question in the air, because the economics make the hypothesis plausible.

And even if you set provenance speculation aside, the pricing still forces a conclusion: either Zhipu's cost structure is dramatically lower than Western peers, or it's willing to subsidize aggressively to buy distribution, or both.

Open weights, expensive reality

Zhipu released GLM-4.7 weights, and in today's discourse "open" still carries moral prestige. But openness at this scale comes with a quiet caveat: the weights are free, running them isn't.

At hundreds of gigabytes in standard precision, this is not a model most independent developers are spinning up on a whim. A Mac Studio capable of running GLM-4.7 at production-grade quantization costs approximately $10,000. In practice, "open" becomes a kind of split-screen reality. Hobbyists get the satisfaction of access and the frustration of hardware limits. Enterprises with real infrastructure can run it, but they're also exactly the customers who can pay for APIs. Inference providers get a new product they can serve fast, at scale, and cheaply, turning the open release into a market for hosted endpoints.

That's why the open-weight move functions less like access expansion and more like brand positioning. It's a way to collect community goodwill while the bulk of real usage still flows through paid access paths.

The result is a familiar dynamic: the people most excited by open weights are often the least able to run them comfortably, and the people most able to run them are the least constrained by API pricing.

Training for your competitor's tooling

If there's one part of this story that deserves to be less data and more plot, it's this: Zhipu didn't just ship a model. It shipped a model designed to fit inside Western agentic coding workflows.

The release notes call out compatibility with Claude Code, Kilo Code, Cline, and Roo Code. That's not a throwaway detail. It's a distribution strategy.

The best way to understand it is to picture what a working developer actually has: not a model, but a stack. An IDE setup. A set of scripts. An agentic workflow. Habits. Muscle memory. A team's shared conventions.

Changing that stack is painful. Swapping the underlying model can be as simple as changing a dropdown.

So Zhipu built for the dropdown.

Get Implicator.ai in your inbox

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Features like "Preserved Thinking," maintaining state across multi-step edits, tests, and revisions, aren't just nice-to-haves. They're compatibility layers. They're what make an agentic coding tool feel coherent across a long session.

This flips the standard competitive logic. Instead of treating Anthropic's tooling ecosystem as Anthropic's advantage, Zhipu treats it as a ready-made distribution channel. Let the Western labs spend time polishing developer experience. Then offer a cheaper engine that snaps into the same chassis.

At €30 a year, the substitution doesn't need to be perfect. It needs to be easy.

What this release signals

Taken individually, none of these moves are shocking. Benchmark charts are marketing. Evaluation windows freeze where they freeze. Synthetic data is everywhere. Open weights are celebrated even when they're hard to run. Tool integrations are standard practice.

Taken together, they form a coherent competitive posture: arbitrage the cost of frontier progress, and ride existing distribution to turn "close enough" into market share.

That's why GLM-4.7 matters even if you decide it's not the best model in the table. It's a model that appears designed to pressure the economics of Western AI, narrowing the practical quality gap while widening the pricing gap at the same time.

The uncomfortable part for Western labs isn't that a competitor shipped a capable model. It's that the countermeasures are limited. You can't easily stop competitors from showing selective charts. You can't prevent people from building around your tooling. And if model outputs remain broadly usable as training signal, every capability improvement becomes a resource that others can harvest.

GLM-4.7 is a serious technical system. But the headline is strategic: the €30 subscription is not a discount. It's an argument about where the profit is, and who gets to keep it.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is Mixture of Experts (MoE) and why does it matter for GLM-4.7?

A: MoE is an architecture where only a fraction of the model's parameters activate for each request. GLM-4.7 has 358 billion total parameters but uses roughly 32 billion per forward pass. This means faster inference and lower compute costs compared to a dense model of similar total size, while still accessing the full parameter count's learned knowledge.

Q: What hardware would I actually need to run GLM-4.7 locally?

A: At FP16 precision, GLM-4.7 requires roughly 716GB of memory. A Q4_K_M quantization compresses this to around 220GB. A Mac Studio with 512GB unified memory (approximately $10,000) can run the quantized version, but developers report that prompt processing speeds make interactive use impractical. Most users will find API access more usable than local deployment.

Q: Is training AI models on other models' outputs legal?

A: In most jurisdictions, yes. Model outputs generally aren't copyrighted. While some terms of service prohibit using outputs to train competing models, enforcement across international boundaries is difficult. The practice, often called distillation or synthetic data training, remains common and legally permissible even if it raises questions about competitive fairness.

Q: What is "Preserved Thinking" and why did Zhipu build it?

A: Preserved Thinking maintains the model's reasoning state across multiple conversation turns. In agentic coding, where a model iterates through file edits, test runs, and debugging cycles, this prevents the model from losing context or contradicting earlier logic. Zhipu built it specifically to work inside tools like Claude Code, where multi-step tasks are the norm.

Read next

Get the 5-minute Silicon Valley AI briefing, every weekday morning — free.