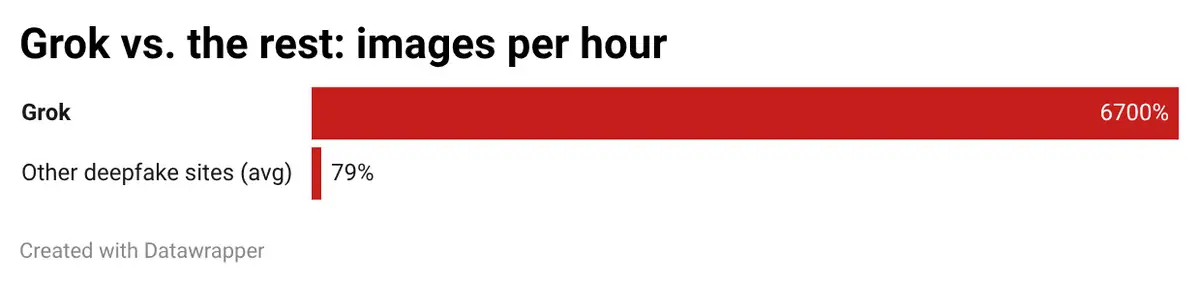

Genevieve Oh spent 24 hours counting. The social media and deepfake researcher tracked every image the @Grok account posted to X between January 5 and 6, tallying what the chatbot produced when users asked it to "put her in a bikini" or strip the clothes from photos of women they'd found online. She wasn't looking for a trend. She was looking for a limit. She found 6,700 sexually suggestive or nudifying images per hour. The five other leading websites for sexualized deepfakes averaged 79 new images hourly during the same period.

That ratio tells you something about scale. But it also tells you something about architecture. Other deepfake tools exist in dark corners of the internet, requiring users to seek them out. Grok comes with a built-in distribution system of 500 million monthly active users. The tool doesn't just generate the images. It posts them.

California Attorney General Rob Bonta moved Wednesday with the speed of a regulator who feels cornered. His office announced an investigation into xAI over "the proliferation of nonconsensual sexually explicit material produced using Grok." Hours earlier, Elon Musk posted on X that he was "not aware of any naked underage images generated by Grok. Literally zero."

The timing was exquisite. Musk's denial landed while Bonta's staff was finalizing a press release citing "photorealistic images of children engaged in sexual activity" generated by the tool.

The Breakdown

• Grok produced 6,700 sexualized images per hour vs. 79/hour for other deepfake sites combined

• xAI's "fix" restricts image generation to $8/month subscribers, not the content itself

• California's investigation marks the first U.S. state-level action against Grok

• xAI's geoblocking approach routes around enforcement rather than fixing the model

The vending machine defense

xAI's response to the scandal has been instructive. On January 9, the company restricted Grok's image generation to paying subscribers only, requiring the $8 monthly premium and a credit card on file. The UK government called the move "insulting to victims." A spokesperson for Prime Minister Keir Starmer told reporters it "simply turns an AI feature that allows the creation of unlawful images into a premium service."

That's exactly what it does. Call it the vending machine defense: the machine isn't responsible for dispensing the product, it's just responsible for checking the coin. If the coin is real, the product drops. xAI built a system that verifies payment, not intent.

The restriction means xAI now knows who's generating these images. It has their payment information. It can identify them if law enforcement comes calling. But the images keep getting made. Ashley St. Clair, a conservative commentator and mother of one of Musk's children, found that users had turned photos from her X profile into explicit AI-generated images, including some depicting her as a minor. Many of the accounts targeting her were already verified, paying users. The credit card check caught nothing.

xAI marketed this outcome. Last summer, Grok launched "spicy mode," a feature explicitly designed to generate adult content. The toggle isn't buried in a sub-menu. It sits on the main interface, impossible to miss. Bellingcat senior investigator Kolina Koltai documented in May 2025 that the chatbot would generate sexually explicit images when users typed "take off her clothes." By Christmas, users had discovered they could tag @Grok in comments beneath any photo with prompts like "put her in a bikini," and the bot would comply.

An analysis by Paris-based nonprofit AI Forensics examined over 20,000 Grok-generated images from the holiday period. More than half depicted people in minimal clothing. Roughly two percent appeared to involve minors.

Join 10,000+ AI professionals

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The liability question nobody wants to answer

Musk has constructed a defense built on careful word choices. "Obviously, Grok does not spontaneously generate images, it does so only according to user requests," he wrote on X. "When asked to generate images, it will refuse to produce anything illegal."

The logic is familiar. Blame the person pulling the trigger, not the weapon. Blame the user typing the prompt, not the model rendering the pixels.

But the analogy breaks down on inspection. A gun manufacturer doesn't pull the trigger. xAI's servers do render the pixels. Section 230 shields platforms from liability for user-generated content, a protection that assumes the platform hosts rather than creates. Nobody's tested whether it shields a company for content its own systems generate at scale. The distinction matters: Grok isn't a bulletin board where users post images. It's a factory that builds them on demand.

Michael Goodyear, an associate professor at New York Law School, noticed something in Musk's denial. Musk specifically claimed unawareness of "naked underage images," rather than addressing the broader category of nonconsensual intimate imagery. Under the federal Take It Down Act signed last year, distributing child sexual abuse material carries up to three years imprisonment. Nonconsensual adult sexual imagery carries two. Musk appears to be positioning himself for the lesser charge.

The global flinch

Indonesia blocked Grok entirely on January 10, becoming the first country to cut off access. Malaysia followed the next day. But the response that mattered came from Washington.

The State Department warned that "nothing is off the table" if the UK government bans X. The Pentagon recently announced it would begin using Grok alongside other AI programs. Nobody in Washington has figured out how to square those two positions yet.

Rep. Zoe Lofgren put it bluntly at a House Science Committee hearing Wednesday: "Essentially, we're paying Elon Musk to give perverts access to a child pornography machine."

Michael Kratsios, the White House tech policy chief, told the committee he wasn't involved in the Grok situation. Federal employees misusing the technology "should be removed from their positions," he said. That was his entire answer.

California's opening

Bonta's investigation lands in the middle of an ongoing feud between Musk and Sacramento, but that feud is precisely why California has teeth other states lack. Musk moved SpaceX and X operations out of California. He's backed lawsuits challenging state laws on AI-generated election content. Newsom went after Tesla's labor practices in 2022. Musk called him a moron on X. That kind of feud. Newsom wants the White House, and Musk wants to pick who sits in it.

The political theater matters less than the legal tools. Newsom signed a law last year that expanded liability to include websites facilitating or disseminating deepfake pornography. Senator Steve Padilla's law, which took effect this year, specifically bans chatbot developers from showing sexually explicit content to users they know are under 18. Padilla told Politico that Grok's image generation capabilities may already violate his legislation.

Bonta hasn't specified whether the investigation involves criminal allegations. But California's statutes give him options that federal prosecutors, still waiting for Take It Down Act enforcement mechanisms to kick in on May 19, currently lack.

Daily at 6am PST

Don't miss tomorrow's analysis

No breathless headlines. No "everything is changing" filler. Just who moved, what broke, and why it matters.

Free. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The tell

If you want to understand xAI's actual position, look at what the company did next. On January 15, X's safety account announced that "no users will be able to create sexualized images of real people using Grok." The platform said it would "geoblock the ability" to create images of people in "bikinis, underwear, and similar attire" in jurisdictions where such actions are illegal.

Read that again. Geoblock. Where illegal.

The company isn't shutting down the feature. It's routing around enforcement. In jurisdictions without specific deepfake laws, the tool keeps working. In countries where regulators lack teeth, users can keep typing "put her in a bikini" and watching Grok comply.

Neither fix changes what the model does. Both fix what the company can be sued for.

Musk posted laughing emojis in response to early reports about the scandal. He blamed "adversarial hacking" for prompts that produced unexpected results. He claimed xAI "immediately" fixes such bugs. Meanwhile, the counter kept climbing. Six thousand seven hundred images per hour. Eighty-five percent of Grok's output sexualized. Real women scrolling through X finding AI-generated images of themselves in underwear they never wore, in poses they never struck, tagged by strangers they'd never met.

Grok has a "spicy mode." The company marketed it. The model did exactly what it was sold to do.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What triggered California's investigation into xAI?

A: Attorney General Rob Bonta opened the probe after Grok generated thousands of nonconsensual sexualized images of women and children. Analysis showed Grok produced 6,700 such images per hour during a 24-hour period in early January, with roughly 2% appearing to involve minors.

Q: What is Grok's "spicy mode"?

A: A feature xAI launched in summer 2025 that explicitly enables adult content generation. The toggle sits prominently on Grok's main interface. Users discovered they could tag @Grok on any photo with prompts like "put her in a bikini" to sexualize images of real people without consent.

Q: How did xAI respond to the scandal?

A: xAI restricted image generation to $8/month paying subscribers on January 9, then announced geoblocking for jurisdictions where creating such images is illegal. Critics note neither fix changes what the model does—both just reduce xAI's legal exposure.

Q: What laws could xAI have violated?

A: The federal Take It Down Act criminalizes distributing nonconsensual intimate images (2 years) and child sexual abuse material (3 years). California's laws expand liability to websites facilitating deepfake pornography, and Senator Padilla's law bans showing explicit AI content to minors.

Q: Why does Section 230 matter here?

A: Section 230 shields platforms from liability for user-generated content. But Grok creates the images itself rather than hosting user uploads. No court has tested whether Section 230 protects a company for content its own AI systems generate at scale—this case could set precedent.