Phison Electronics CEO Pua Khein-Seng warned this week that many consumer electronics companies could go bankrupt or exit product lines by the end of 2026, driven by a global memory shortage that shows no signs of easing. In a televised interview with Ningguan Chen of Taiwanese broadcaster Next TV, confirmed by The Verge through native Chinese speakers, Pua said at least one of the three major NAND foundries is now demanding three years of prepayment for capacity, a condition without precedent in the electronics industry. His own customers' fulfillment rate has dropped below 30 percent.

The warning carries weight because of who is delivering it. Phison controls roughly 20 percent of the global SSD controller market and 40 percent of automotive storage, according to Tom's Hardware. Pua sits at the junction where memory suppliers meet the companies that build phones, laptops, cars, and televisions. When he describes himself as a "memory beggar," he is talking about begging on behalf of a company that moves billions of dollars in storage controllers every year.

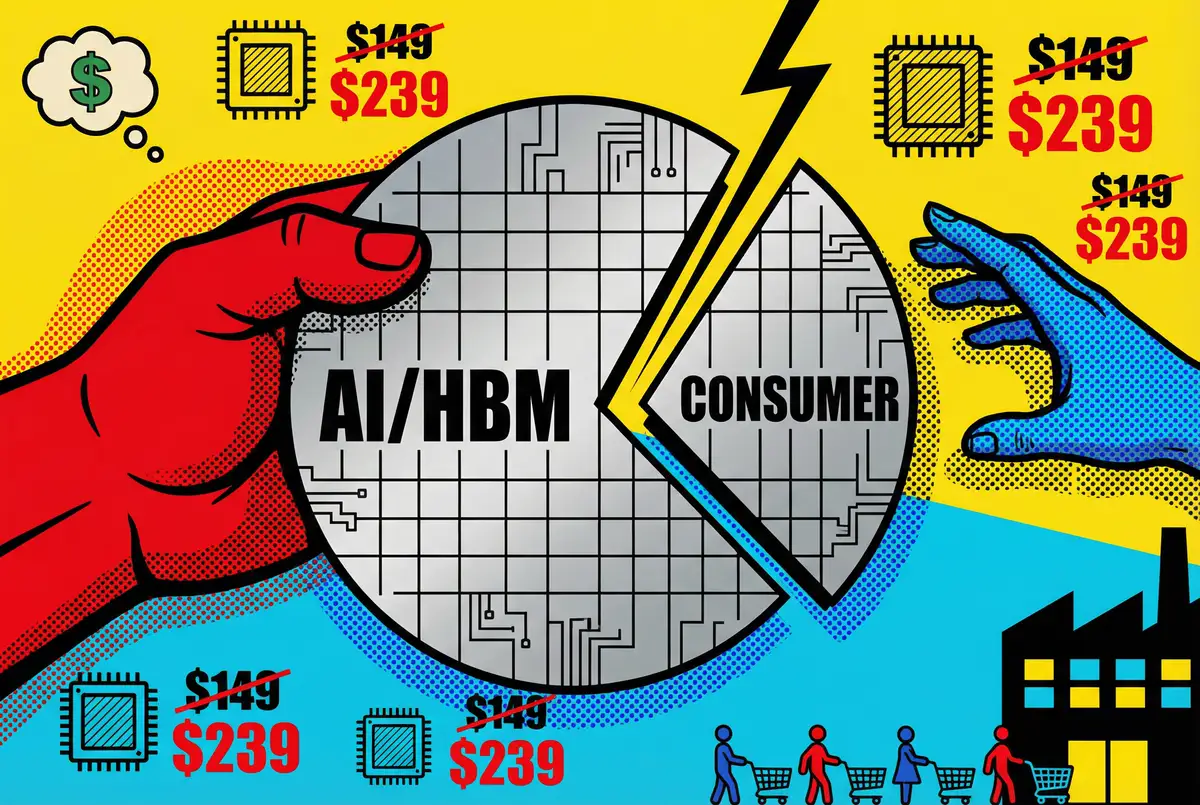

AI data centers are consuming the vast majority of the world's DRAM and NAND flash production, and the three companies that control 93 percent of the DRAM market, Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron, have chosen to prioritize high-margin server memory over consumer-grade chips. The data Pua laid out describes something worse than a supply blip. This is rationing. The data center cuts to the front of the line.

The Breakdown

- Phison CEO warns consumer electronics companies face bankruptcy by end of 2026 as global memory shortage worsens

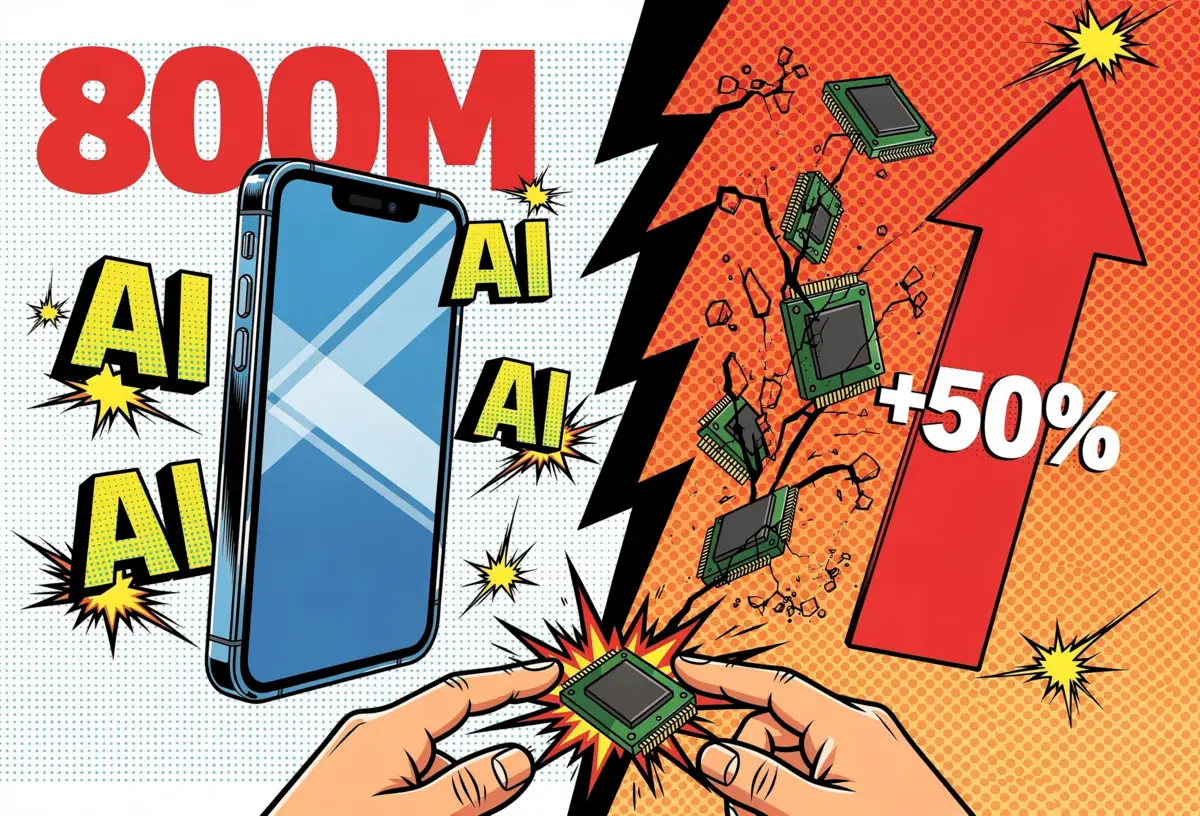

- 8GB eMMC prices jumped from $1.50 to $20 in 2025; smartphone production could drop up to 250 million units

- Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron control 93% of DRAM and prioritize AI data center orders over consumer chips

- Internal foundry estimates suggest the shortage will persist until 2030, with some projections stretching a full decade

The price of getting what's left

One number from the interview makes the scale real. An 8GB eMMC module in a car dashboard cost $1.50 at the start of 2025. By December it was twenty dollars. Thirteen times more. And at that price, companies are still lining up, because the alternative is not shipping the car at all.

Smartphone production could drop by 100 to 250 million units this year, Pua said. At the high end, that wipes out a fifth of every phone built on the planet. PCs and televisions will lose volume too. Pua told his interviewer that he warns his clients directly. "If the first quarter of this year is painful, really painful, then by year-end, they'll definitely jump off a building."

That kind of language is unusual from a CEO who makes his living selling to the companies he's describing. Pua sounds cornered. This isn't a man performing concern for an earnings call or calibrating expectations for investors. He is delivering a diagnosis to people he thinks are about to get hurt.

Consumer-facing companies absorb memory costs differently than data center operators. NAND flash can account for 20 percent of a smartphone's total bill of materials, Pua explained, compared with roughly 5 or 6 percent of a server's price. When memory prices spike fivefold, the smartphone maker takes a body blow. The hyperscaler shrugs.

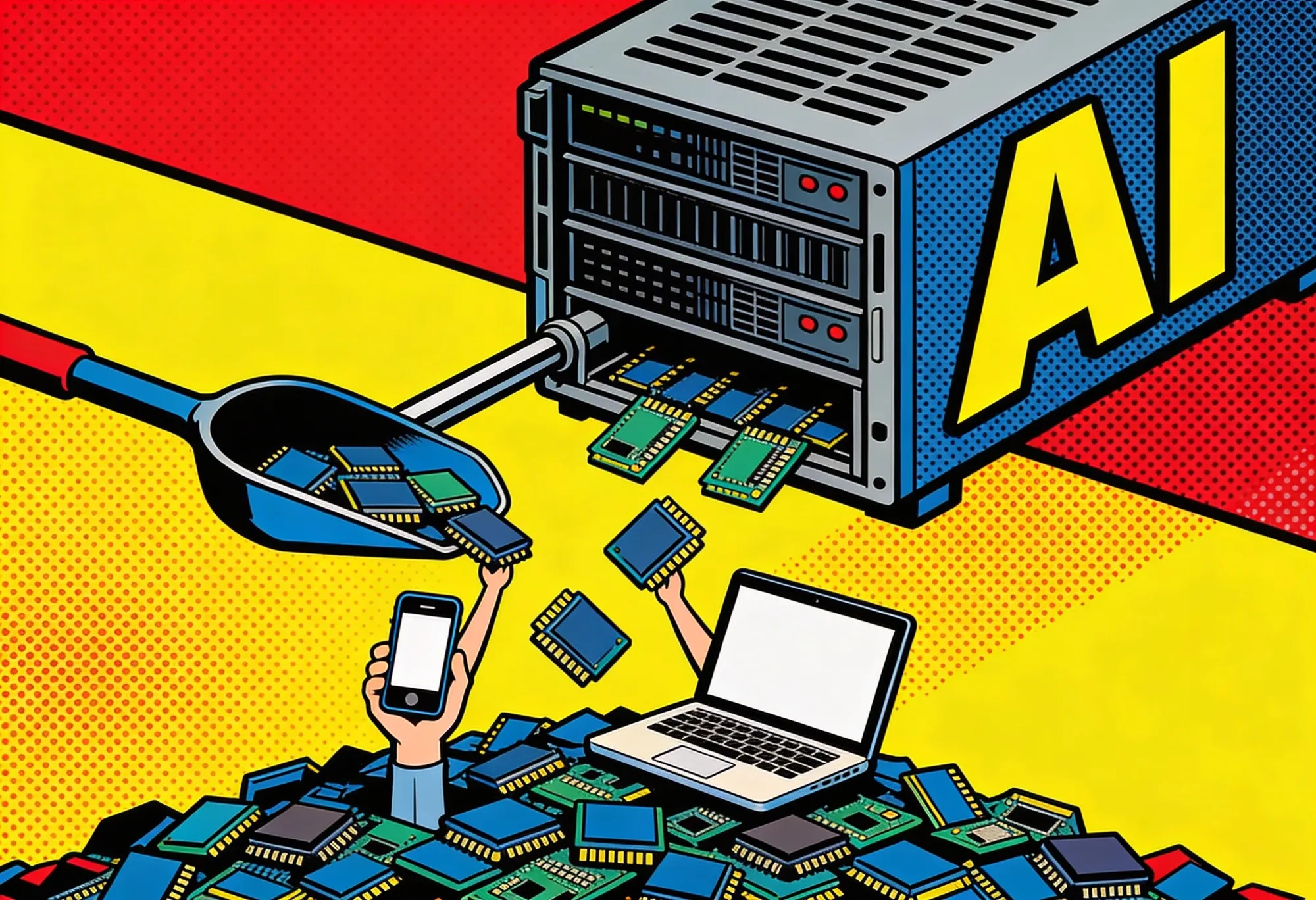

AI eats the memory supply

All three major memory makers are building new fabrication facilities, but slowly, deliberately. Last time they expanded fast, oversupply crashed prices and gutted margins. That burned badly enough to reshape how they allocate capacity. The indifference toward consumer buyers is now baked in. Keep output constrained. Let AI data center demand set the price. High-bandwidth memory for AI accelerators commands premium margins. Standard DRAM for a laptop does not.

Dell COO Jeff Clarke, who has spent decades managing the company's supply chain, put it plainly in a December interview with Wired. "I've been at this a long time. This is the worst shortage I've ever seen. Demand is way ahead of supply. And it's driven by AI."

DRAM contract prices climbed roughly 40 percent in the final quarter of 2025, according to Citrini Research. Analysts expect another 60 percent increase in the first quarter of this year. Spot market prices have multiplied fivefold since September. Western Digital has already sold its entire hard drive production for 2026 and is short for 2027 and 2028.

Pua warned the pressure will get worse. The AI industry is moving from training models to running them. Two very different demands on memory. Training is a one-time build, expensive but finite. Inference is permanent. It serves millions of users every day, every query generating data that has to live somewhere. That somewhere is the same NAND flash that goes into your phone and your laptop.

Nvidia's upcoming Vera Rubin AI platform alone could consume more than 20 percent of global NAND production, according to WCCFTech's reporting on Pua's interview. Enterprise demand, he said, has not been fully factored into most industry forecasts. When it hits, the current shortage will look mild by comparison.

Hoarding as survival strategy

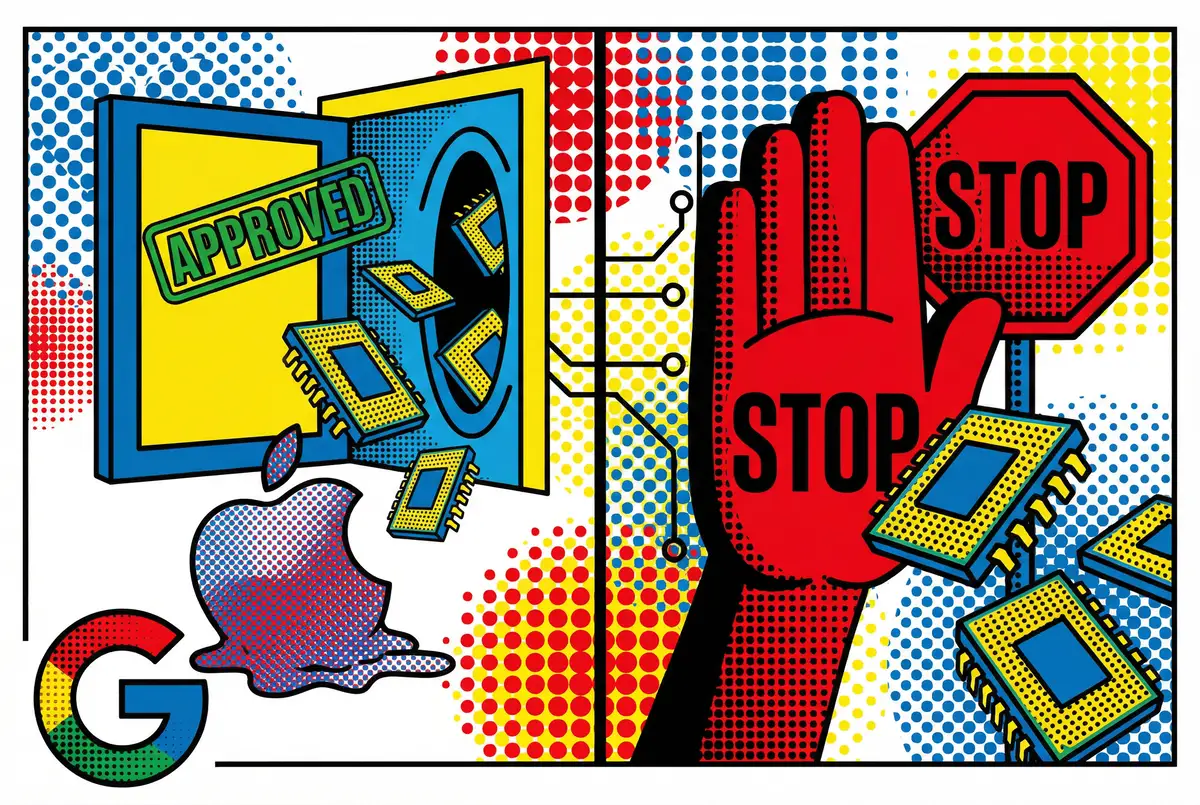

Laptop and PC manufacturers have gone defensive. They are hoarding. Dell, HP, Asus, and Lenovo have all told shareholders they are working to secure long-term DRAM supply. Clarke described it as the number one rule of Dell's supply chain: never run out of parts.

Hoarding works for the biggest buyers. It makes things worse for everyone else. Smaller companies, the ones Pua is warning about, lack the purchasing power to lock in supply for years at a time. They are the ones who will exit product lines or disappear entirely. A second-tier phone brand or a midsize TV manufacturer doesn't have Dell's supplier relationships. They buy on the spot market at five times last year's prices. The margin on a budget phone doesn't survive that kind of hit. These are the companies Pua was talking about when he mentioned jumping off buildings.

Price increases have already started showing up at retail. Asus officially raised prices and adjusted product configurations on the last day of 2025. A leaked internal Dell document suggested prices could rise by as much as 30 percent this year. RAM kits that sold for reasonable prices twelve months ago now carry four-figure tags.

You can see the downstream effects spreading. Valve confirmed last week that the Steam Deck OLED will be "intermittently" out of stock because of the memory crisis. Sony is reportedly looking at pushing the PlayStation 6 all the way to 2029, and Nintendo's Switch 2 may come in pricier than expected. Nvidia might not ship a consumer gaming GPU at all this generation. First time in thirty years.

Stay ahead of the curve

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

One company's gamble on a workaround

Phison brought more than warnings to the table. At CES in January, Pua presented aiDAPTIV, an add-in SSD cache that lets faster NAND flash shoulder work normally handled by DRAM, especially AI processing on local hardware.

Say the technology works. A laptop manufacturer ships a machine with 16 GB of DRAM instead of 32 and hits the same AI benchmarks. Half the most expensive component, gone. MSI and Intel have signed on early. The card drops into an existing PCIe slot, no redesign needed.

A startup called Ventiva is approaching the problem from a different angle entirely. Its solid-state cooling technology replaces traditional fans with an ionic air movement system, freeing physical space inside laptops. Space that could be filled with additional memory modules. CEO Carl Schlachte put the constraint in three words. "The holy trinity of memory is capacity, bandwidth, and topology." Topology here means the physical distance between RAM and the CPU. Smaller motherboards put RAM closer to the processor, and more of it can fit.

Both approaches rest on the same bet. If enough AI processing moves from the cloud onto local devices, demand for consumer-grade DRAM becomes too large and too profitable for memory manufacturers to ignore. Right now the money is in server memory. Phison and Ventiva are arguing that the economics of on-device AI could flip that calculation, but flipping it requires convincing laptop OEMs, chip designers, and memory manufacturers to tell a unified story. None of them have strong incentives to go first.

Schlachte didn't sugarcoat the alternative. "We blow our inheritance money on the data center," he told Wired. "And in order to pay for it, we enshittify the whole thing."

The timeline nobody wants to hear

Pua's most unsettling prediction was about duration. Internal estimates from memory foundries, he said, suggest the shortage will persist until 2030. Some projections stretch to a full decade. When foundries demand three years of cash upfront for capacity reservations, they are telling the market exactly how long they expect supply to remain tight.

AMD has already added the shortage to its official risk disclosures. "There is currently an industry-wide memory shortage as the demand for such components has outpaced supply," the company stated in a recent filing.

The Verge noted one important detail about the interview's framing. It was the host, Ningguan Chen, who asked whether companies would shut down and whether product lines would be discontinued. Pua confirmed rather than volunteered the predictions. A CEO running a company that depends on a healthy consumer electronics industry does not cheerfully agree that his customers are going to go bankrupt. He agrees because the data leaves him no other option.

For consumers, the effects will arrive gradually and then all at once. Higher prices on phones, laptops, and gaming consoles come first. Fewer configuration choices follow. Then entire product lines go dark. The companies making those products don't have the cash reserves or the purchasing clout to survive a shortage that could last the rest of the decade.

Three companies decide where the memory goes. Right now, the data center gets first pick. The phone in your pocket gets what's left.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is there a global memory shortage?

AI data centers are consuming the majority of the world's DRAM and NAND flash production. Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron control 93 percent of the DRAM market and have chosen to prioritize high-margin server memory for AI accelerators over consumer-grade chips. DRAM contract prices climbed 40 percent in Q4 2025, with analysts expecting another 60 percent increase in Q1 2026.

How long will the memory shortage last?

Phison CEO Pua Khein-Seng said internal estimates from memory foundries suggest the shortage will persist until 2030. Some projections extend to a full decade. At least one major NAND foundry is now demanding three years of prepayment for capacity reservations, signaling manufacturers expect tight supply for years.

What is Phison's aiDAPTIV technology?

aiDAPTIV is an add-in SSD cache that lets faster NAND flash handle work normally done by DRAM, especially AI processing. If it works as planned, laptop manufacturers could ship machines with 16 GB of DRAM instead of 32 while maintaining the same AI performance. MSI and Intel have announced early support.

Which consumer electronics products will be affected?

Smartphones, PCs, televisions, and gaming consoles are all at risk. Pua predicted smartphone production could drop by 100 to 250 million units in 2026. Valve's Steam Deck OLED is already intermittently out of stock. Sony may delay the PlayStation 6 to 2029, and Asus raised prices at the end of 2025.

Why don't memory manufacturers build more factories?

They are building new facilities, but deliberately slowly. The last time memory makers expanded aggressively, oversupply crashed prices and destroyed margins. Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron have decided to keep production constrained, prioritizing high-margin AI data center memory over consumer supply.

Know someone who'd find this useful? Forward this article. They can subscribe free here.