Munich startup Sitegeist has raised €4 million in a pre-seed round to deploy autonomous robots that strip deteriorated concrete from aging bridges, tunnels, and parking structures, the company announced on Sunday. B2venture and OpenOcean co-led the round, joined by UnternehmerTUM Funding for Innovators and a lineup of prominent German angels including Verena Pausder and Lea-Sophie Cramer. The money goes toward hiring engineers and putting Sitegeist's modular robot systems onto active construction sites across Germany.

The Breakdown

• Sitegeist raised €4M pre-seed from B2venture and OpenOcean to deploy autonomous concrete repair robots across German construction sites.

• Germany's infrastructure repair backlog runs into hundreds of billions of euros, with renovation firms booked years out and skilled workers retiring faster than replacements arrive.

• Existing demolition robots from Brokk, Aquajet, and Conjet require one operator per machine. Sitegeist's autonomous approach lets one specialist oversee multiple robots simultaneously.

• The Munich startup, formerly Aiina Robotics, already has machines on active job sites and plans to expand into sandblasting and drilling with modular tool heads.

Four million euros won't fix a bridge. But the problem Sitegeist is attacking dwarfs the check. KfW, Germany's state development bank, put the country's repair backlog at hundreds of billions of euros last year. Go stand on any Autobahn overpass and you can see it. Bridge decks from the '60s and '70s are giving out under modern truck loads. Parking garages drip concrete onto the cars below, and that's the stuff you can actually see. Tunnel linings crumbling behind temporary netting. The renovation firms that handle this kind of work? Booked solid. Some of them years out. France, Italy, and Britain face the same ugly math, infrastructure poured to last 50 years that is now pushing 70. Governments know the numbers. They have known them for years. The problem is not awareness. It is that the people who can actually do the work are retiring faster than the industry can replace them.

The bottleneck is not money or political will. It's bodies. Few industries have a workforce shortage this physically dangerous. When there aren't enough qualified workers to repair a bridge, the bridge doesn't wait. It keeps cracking. You've probably driven across a German overpass with a weight restriction sign that wasn't there five years ago. That sign is the backlog, right there on the guardrail.

Jackhammers, water jets, and the precision problem

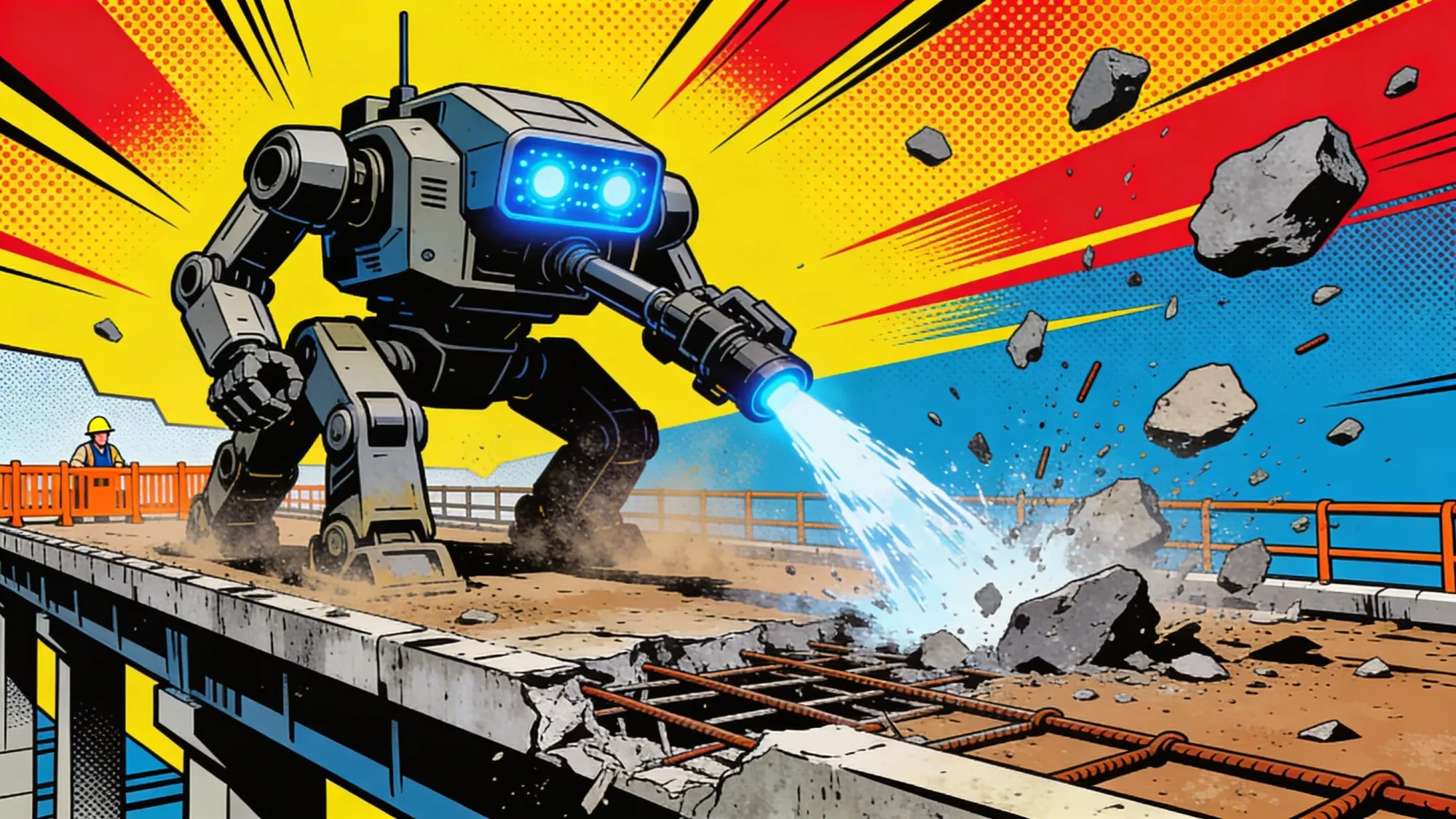

Ask anyone who has worked a concrete renovation job and they'll rank it among the worst gigs on a site. Bridge decks and tunnel walls don't collapse all at once. They rot in patches. Somebody has to show up with heavy equipment and grind away at it, centimeter by centimeter. You don't know if the next layer down is still good until you get there. The industry calls it hydrodemolition when you blast water at thousands of bars of pressure, or you go with abrasive blasting, steel grit flung hard enough to strip concrete off rebar. Both punish mistakes. Cut too deep and you slice through the reinforcement steel holding the whole structure together. Too shallow and the patch fails in a few years.

Crews wear full face shields, ear protection, heavy gloves, because a water jet that cuts concrete will go through skin before you feel it. They work on scaffolding, inside tunnels, on bridge undersides where the wind doesn't quit. And every single job is different. One bridge might have even wear across the whole deck. The next has damage clustered around expansion joints and drainage points, places where water pooled for twenty years. Corners, curved ceilings, column bases. The geometry never cooperates. That's why nobody has managed to automate this work. Not yet.

Sitegeist's robots are designed to handle it without a human hand on the controls. The machines carry onboard sensors that read the concrete surface in real time, adjusting pressure, angle, and speed as they encounter different material conditions. The machines don't need a pre-existing 3D model of the structure, no BIM data, no site-specific reprogramming before they start work. The robot scans the surface, maps the damage, and begins stripping.

"Infrastructure renovation is hitting a critical bottleneck, especially in concrete repair," CEO Dr. Lena-Marie Patzmann said. "Today, deteriorated concrete is still removed using manually-intensive processes that are hard to scale."

The company told SiliconANGLE its robots can strip concrete up to 10 times faster than a manual crew. That's a bold number, and independent verification will matter once deployments scale. But even a threefold or fourfold improvement would change the math for renovation firms drowning in backlogs they cannot staff.

Why tele-operation can't clear the backlog

Sitegeist is not entering an empty market. Concrete demolition and renovation robots have existed for decades. Swedish manufacturers Brokk, Aquajet, and Conjet sell heavy-duty machines used on job sites across Europe and North America. They are proven and rugged, but built around a design philosophy Sitegeist believes is reaching its limits. The Scandinavian firms have shown little urgency about autonomy. They have a profitable installed base and customers who already know how to run tele-operated equipment. That comfort is the opening Sitegeist is trying to exploit.

Those Swedish machines are tele-operated. A skilled worker with a remote control guides every movement of the robot in real time. One operator, one machine, continuous attention. So the robot takes the beating instead of a worker's shoulders and spine. Real progress. But someone is still glued to the controls, choosing every cut, every angle, every pass. The labor bottleneck shrinks. It does not break.

Sitegeist wants to break it. Full autonomy. One specialist overseeing multiple robots working at the same time instead of one operator piloting a single machine. Claus Carste, Sitegeist's chief product officer, researched teleoperation at the Technical University of Munich before deliberately shifting his work toward machines that decide for themselves. The math is plain: if one person can supervise three or four autonomous robots rather than piloting one tele-operated unit, you've tripled effective capacity without hiring a single new worker.

"The most exciting AI-powered robots today don't have fingers and thumbs," said Sam Hields, partner at OpenOcean. Sitegeist's machines, he added, are "purpose-built to solve real-world problems."

Stay ahead of the curve

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Hields is taking a shot at the humanoid crowd, and he knows it. Venture money has poured into human-shaped robots for two years straight. Figure AI alone raised $675 million in a single round nearly two years ago. The humanoid pitch is one form factor, any task. Sitegeist's backers are making the opposite wager. A squat, weather-hardened machine that does one thing extremely well on the worst job sites imaginable may be worth more than a humanoid that can theoretically do everything but has yet to prove it can reliably do any single industrial task.

Whether Sitegeist's own robots can deliver at real-world scale remains an open question. Autonomy inside a clean factory is one challenge. Autonomy on a weather-exposed, half-demolished bridge deck is a different one entirely. Rain. Wind. Concrete dust in clouds thick enough to choke sensors. Temperature swings from January frost to August heat. The distance between a lab prototype and a machine that performs reliably at 7 a.m. on a wet Monday morning on a bridge over the Rhine is where most robotics startups stall out.

From Aiina Robotics to the Golden Pretzel

Sitegeist spun out of the Technical University of Munich, specifically from Prof. Matthias Althoff's robotics research group, the same lab that produced RobCo. Althoff's institute has quietly become a production line for commercial spin-offs, and Sitegeist, which competed under the name Aiina Robotics until recently, won the Golden Pretzel at Munich's Bits & Pretzels startup conference last year. It also took the Munich Startup Special Prize.

Patzmann's profile is unusual for a construction robotics founder. She studied at the University of St. Gallen, one of Europe's top business schools, and holds a bachelor's degree in philosophy. It is the kind of background that raises eyebrows in deep-tech circles, but it also means the company's pitch to investors and construction firms comes from someone trained to think about what technology does to work, not just how it works. Her three co-founders carry the engineering credentials: CTO Julian Hoffmann, COO Nicola Kolb (a former fellow of the Bayerische EliteAkademie), and CPO Carste all came through TUM's robotics and AI programs. Three of four founders are roboticists by training. Patzmann is the one who knows how to put their work in front of customers and capital.

The angel list carries weight in the German startup world. Verena Pausder is one of the country's most visible tech founders and investors. Lea-Sophie Cramer built and sold the e-commerce platform Amorelie. B2venture, the co-lead VC, backed DeepL and SumUp from their earliest stages. Industrial angels Alexander Schworer and Mario Wettengel bring actual connections in the construction sector, the kind of relationships that get a robot prototype onto a real job site instead of keeping it trapped inside a demo reel.

"The way concrete is removed today by workers is devastating and extremely arduous," said Florian Schweitzer, partner at b2venture. "This is the perfect case for augmenting humans with robots."

Four million euros against hundreds of billions in damage

Sitegeist already has machines on active job sites. The company works directly with German concrete renovation firms, running its robots in the same weather, dust, and physical conditions that human crews face daily. These are not carefully staged pilot programs. They are commercial tests on real structures with real deadlines, and the pre-seed funding will expand those partnerships and bring additional sites online.

The longer roadmap stretches past concrete removal. Sitegeist's modular platform is designed to eventually handle sandblasting, drilling, and other renovation work that fits the same pattern: physically grueling, precision-dependent, chronically short on workers willing to do it. Each new capability means attaching a different tool head to the same autonomous chassis, the same sensors, the same navigation and perception stack. In principle, solving autonomy for hydrodemolition solves most of the hard problem for sandblasting too. Whether construction sites cooperate with that principle is a question the company has not yet answered at scale.

Getting from four million euros in pre-seed funding to an operation that meaningfully dents a multi-hundred-billion-euro infrastructure crisis will take several more funding rounds, years of difficult engineering, and a kind of customer patience that construction companies, deeply risk-averse about new technology and nervous about anything unproven on a live structure, rarely extend to startups. Swedish incumbents carry decades of field data and global service networks built from hundreds of real installations. What Sitegeist has is a thesis: that a robot reading the surface as it goes, adapting to corners and columns and ceilings without anyone's hand on the controls, can crack a labor bottleneck that remote-controlled machines never solved.

Concrete dust. Pressurized water. Steel rebar millimeters beneath the surface. The test is not in a pitch deck or an investor memo. It's in the bridge.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What does Sitegeist's robot actually do on a construction site?

A: It strips deteriorated concrete from bridges, tunnels, and parking structures using hydrodemolition or abrasive blasting. Onboard sensors read the surface in real time, adjusting pressure, angle, and speed without needing a pre-existing 3D model or BIM data. The company claims its machines work up to 10 times faster than manual crews.

Q: How is Sitegeist different from existing demolition robots?

A: Swedish manufacturers Brokk, Aquajet, and Conjet sell tele-operated machines that still require one skilled worker per unit controlling every movement. Sitegeist's robots are designed for full autonomy, meaning one specialist can supervise three or four machines working simultaneously instead of piloting a single unit.

Q: Who founded Sitegeist and where did the technology come from?

A: Four co-founders from the Technical University of Munich: CEO Dr. Lena-Marie Patzmann (business and philosophy background from St. Gallen), CTO Julian Hoffmann, COO Nicola Kolb, and CPO Claus Carste. The company spun out of Prof. Matthias Althoff's robotics research group, the same lab that produced RobCo.

Q: How big is the infrastructure repair problem in Germany?

A: KfW, Germany's state development bank, estimated the country's repair backlog at hundreds of billions of euros. Bridge decks poured in the 1960s and 1970s are failing under modern truck loads. Renovation firms are booked years out, and the skilled workforce is shrinking as workers retire faster than replacements enter the trade.

Q: What is Sitegeist's longer-term product roadmap?

A: The modular platform is designed to eventually handle sandblasting, drilling, and other renovation work by swapping tool heads on the same autonomous chassis. Solving autonomy for hydrodemolition addresses most of the hard perception and navigation problems needed for adjacent tasks, though the company has not yet proven this at scale.