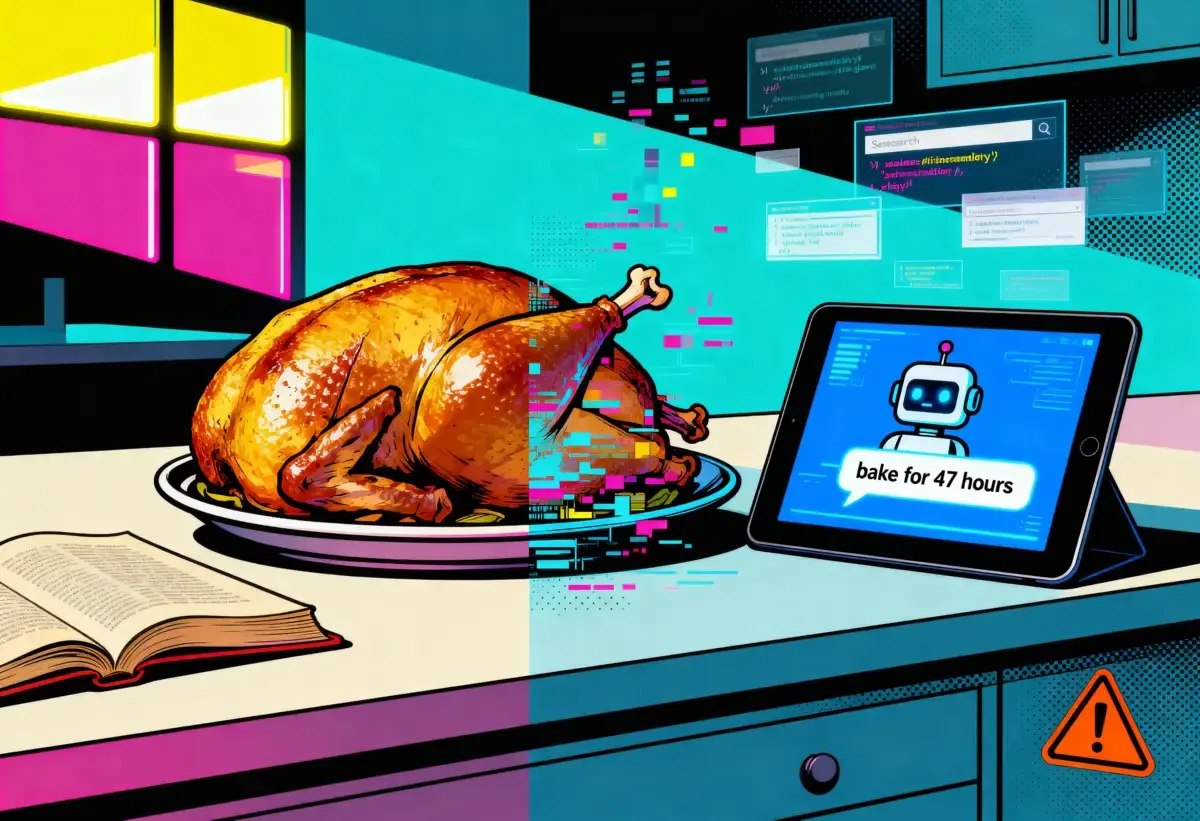

Somewhere in Google's servers, a language model is confidently instructing someone to bake a Christmas cake for four hours. The actual recipe calls for ninety minutes. The difference between these two numbers is roughly the difference between dessert and aite sample.

This Thanksgiving, millions of Americans will search for recipes online and encounter something that looks helpful, sounds authoritative, and has never touched a stove. AI-generated cooking content has metastasized across every platform where people seek culinary guidance, from Google's AI Overviews to Pinterest's recommendation engine to Facebook's algorithmic feed. Food creators who've spent years perfecting dishes now watch their traffic evaporate while synthetic instructions tell home cooks to pour sauce over corn husks they're supposed to remove first.

The tamales, apparently, did not test well with focus groups.

The Breakdown

• Food creators report 40-80% traffic drops as Google's AI Overviews intercept recipe searches with untested instructions

• The Woks of Life built the only comprehensive English-language Chinese cooking resource; AI now summarizes it without attribution

• Unlike other domains, recipe errors only surface when someone cooks them, creating a verification gap AI exploits

• As creators exit, AI systems will increasingly recycle synthetic content, degrading the knowledge base they depend on

When Algorithms Learn to Cook (Badly)

Google's AI Overviews represent the company's bet that users want answers, not websites. Type a recipe query, and you'll often see a summary panel that stitches together instructions from multiple sources. A Frankenstein approach to cuisine. Cooking as multiple-choice test where all answers might be partially correct.

One food creator discovered that Google's AI grabbed his ingredients list and combined it with another blogger's instructions, presenting this chimera as the authoritative answer. It appeared above his own link even when users searched for his brand by name. The result: a 30% drop in click-through rates for cocktail recipes that he'd actually made and photographed.

This is the core absurdity. Large language models cannot taste. They cannot smell onions caramelizing or feel when dough reaches the right consistency. They process text about cooking the same way they process text about quantum mechanics or celebrity gossip, as patterns to predict and reproduce. When a model suggests baking times, it's not reasoning from principles of heat transfer. It's guessing which number appears most frequently in similar contexts.

Sometimes that guess is spectacularly wrong. And unlike a typo in an article about quantum mechanics, a wrong number in a recipe has consequences you can smell from the next room.

Cultural Knowledge Has a Price. Google Isn't Paying It.

The ruined dinners and frustrated home cooks make for good anecdotes. But there's something uglier underneath.

Sarah Leung's family runs The Woks of Life. They've spent years on it. What they built isn't just another recipe blog, it's become one of the only comprehensive English-language resources for Chinese cooking techniques. Reference material on traditions and ingredients. Cultural context that matters if you actually want to understand what you're making. Before her family started writing, much of this information simply didn't exist in English anywhere online.

AI summaries have now overtaken search results for many of those ingredients.

Think about that for a second. The Leungs documented knowledge that wasn't available to English speakers. Google's AI scraped it, compressed it into panels, and now serves it to users who never learn where it came from. The family is left wondering whether new reference guides are even worth publishing anymore.

Why would they be? Spend months researching an obscure ingredient. Write it up carefully. Google summarizes your work in three sentences. The searcher gets their answer and moves on. You get nothing, not even credit. That's the deal now.

And it's not really about traffic numbers or ad revenue, though those matter. It's about whether anyone will bother documenting culinary knowledge at all.

Recipes don't just exist. Someone has to learn a technique, try variations, figure out what works, write it down, share it. That's how food traditions survive. The Woks of Life is exactly this kind of cultural work, a family making their heritage accessible in another language. Except now that documentation feeds systems that reproduce it endlessly. No mechanism for reciprocity. No reason to keep contributing.

Chinese cooking traditions developed over generations. Years of work to document them in English. Seconds for an algorithm to summarize. Zero flowing back.

The Content Farm Singularity

Carrie Forrest ran Clean Eating Kitchen with about ten employees. She runs it alone now. Everyone else is gone. Eighty percent of her traffic vanished over two years.

Her worry is grimly elegant: eventually, AI will be talking to itself.

She's probably right. The economics are creating a feedback loop.

Human creators produce tested recipes. AI systems scrape and summarize. Traffic to humans drops. Some humans quit. AI systems have less new content to scrape. They start recycling AI-generated content. Quality degrades. But users have been trained to trust the summary panel by then. The original creators have moved on to jobs that pay.

Pinterest's recommendation emails used to surface seasonal dishes from human creators. Now they increasingly suggest AI-generated meals. Facebook's algorithm pushes AI food images above posts from actual cooks, images of dishes that look stunning and are often impossible to recreate. One blogger noted that tutorial videos specifically advise targeting elderly Facebook users with AI food content. The demographic least able to spot synthetic cooking advice gets bombarded with it.

At least four bloggers have discovered AI-generated replicas of their entire recipe libraries. Photos subtly altered. Instructions lightly rephrased. Different domains. Because nothing is copied verbatim, traditional takedown tools don't work cleanly.

Bjork Ostrom, who runs Pinch of Yum with his wife, found a German-language mirror of his entire website. It included AI-altered copies of his food photography. And synthetic, subtly distorted images of his wife and children.

Google's Defense, and Its Limits

Google told reporters that its AI Overviews are "often a helpful starting point to learn about a dish," adding that the company is "focused on making it easy for people to discover and visit useful sites that have a good user experience."

That phrase about user experience carries a subtle accusation. Food blogs became notorious for SEO-driven personal essays that forced readers to scroll through paragraphs of backstory before reaching actual instructions. Google's algorithm rewarded longer content, so bloggers wrote longer content. Now Google implies that AI summaries exist because those same blogs are unpleasant to navigate.

There's truth here. Also irony. The platform's incentive structure created the problem its AI now claims to solve. Those 2,000-word essays about grandmother's emotional journey with casseroles? Nobody wrote those for fun. Google's ranking system rewarded length. Bloggers responded rationally. Now Google points to the clutter and offers a solution.

But replacing human-tested recipes with AI-assembled summaries doesn't actually fix anything. It just moves the dysfunction. Instead of scrolling past an essay to reach a tested recipe, users get a synthetic recipe immediately. Faster, sure. Better? Depends on whether you care if the result is edible.

The Verification Problem

Recipe content occupies an unusual position in the information ecosystem. Unlike news articles or product reviews, recipes contain implicit claims that can only be verified through physical execution. You cannot fact-check whether a cake will rise by reading more carefully. You have to bake the cake.

This creates an opening for AI slop that doesn't exist elsewhere. A language model generating financial advice might be immediately contradicted by market data. Historical claims might be checked against records. But a model generating recipes faces no immediate accountability. The feedback loop between publication and correction runs through actual kitchens, actual ingredients, actual ruined dinners.

By the time enough people burn enough cakes to establish that a particular AI recipe doesn't work, the content has proliferated everywhere. Pinterest feeds overflow with images of food that attached instructions won't achieve. Facebook content farms use AI-generated images of impossible dishes to capture clicks.

The fundamental promise of a recipe, that someone has actually cooked it before you, is gone. Users can't tell until they've already bought the ingredients.

What Dies When Creators Stop Creating

Yvette Marquez-Sharpnack has written about Mexican food for fifteen years at Muy Bueno. She recently posted two AI-generated tamale images for her 190,000 Facebook followers, pointing out what was wrong.

One showed sauce poured directly over corn husks. You're supposed to remove those before eating. The other showed tamales lying flat in a steamer. They need to stand upright. Otherwise the masa doesn't cook through evenly.

Small details. The kind you learn from actually making tamales a few hundred times. Not from predicting which words follow "tamale" in a training corpus.

Her husband tried a Facebook recipe for maraschino cherry chocolate chip cookies last Christmas. Photos looked perfect. Too perfect, maybe, uniformly pink. He trusted the post because "it was on Facebook." The result was a melted sheet of dough with a flavor she described as disastrous.

The cookies didn't know they were supposed to hold together. Neither did the algorithm.

Cultural food knowledge is particularly vulnerable here. Techniques passed down through generations resist clean textual description. The right consistency of masa. The sound of oil at the correct temperature. When caramelization tips into burning. These are embodied skills, learned through repetition and correction. AI systems can reference them. They can't replicate them.

When the humans who hold this knowledge stop publishing because the economics collapsed, that knowledge doesn't get preserved in training data. It disappears.

The Quiet Withdrawal

Many bloggers describe entering this holiday season with what one called "a mix of anxiety and resignation." Traffic has become unpredictable. Content appears in AI summaries without compensation. Photos circulate on platforms with wrong instructions attached.

Some are reconsidering whether to publish at all. Others warn their audiences to verify sources, check URLs, look for real "about" pages, be suspicious of images that look too polished.

The Woks of Life family made Chinese cooking techniques available in English for the first time. Now they watch those techniques get compressed into AI panels while wondering if future work is pointless.

Knowledge ecosystems don't collapse dramatically. There's no confrontation. Just a quiet calculation, repeated across thousands of individual creators, that the effort isn't worth it anymore. One person at a time deciding their tested recipe, the cultural expertise behind it, years of experimenting in actual kitchens, none of it can compete with an algorithm that generates cooking times without ever having cooked.

The algorithm will keep producing recipes. It just won't know which ones work.

Why This Matters

- For home cooks: AI-generated recipes bypass the verification that makes cooking advice trustworthy. Until platforms build quality controls, recipe searches have become a game of distinguishing expertise from synthetic confidence. Check sources. Look for human authors. Distrust perfection.

- For cultural preservation: Culinary traditions survive through documentation. When food blogging economics collapse, specialized knowledge, especially from underrepresented cuisines, stops getting written down. AI can summarize what exists. It cannot create what was never documented.

- For the information ecosystem: Recipe content previews what happens when AI summaries replace original sources everywhere. Creators who produce knowledge are being cut out of the value chain while platforms capture the benefits. Long-term, the internet knows less because the incentives to create have been destroyed.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How can I spot an AI-generated recipe before wasting ingredients?

A: Look for images that appear too perfect or uniformly styled. Check if the site has a real "about" page with an actual person behind it. Be suspicious of instructions that lack specific visual cues or timing details. AI recipes often botch small technical points—like showing tamales lying flat in a steamer when they should stand upright for even cooking.

Q: How much traffic have food bloggers actually lost to AI summaries?

A: The damage is severe across the board. One creator's turkey recipe traffic dropped 40% year over year. Clean Eating Kitchen lost 80% of traffic over two years, forcing layoffs of roughly 10 employees. Inspired Taste reported 30% lower click-through rates when AI Overviews appeared. Some Pinterest-dependent bloggers saw referral traffic fall from 25% to 11% of total visitors.

Q: Why doesn't Google just link to recipes instead of summarizing them?

A: Google believes users want quick answers, not website visits. The company calls AI Overviews a "helpful starting point" and points to food blogs' cluttered design—those long personal essays before recipes—as justification. The irony: Google's own ranking algorithm rewarded longer content for years, creating the problem its AI now claims to solve.

Q: Could AI ever actually test a recipe before publishing it?

A: Not meaningfully. Language models predict text patterns; they can't taste, smell, or feel texture. When AI suggests a baking time, it's statistically guessing based on similar recipes—not reasoning from heat transfer. The Christmas cake disaster (AI suggested 4 hours vs. actual 90 minutes) shows how badly these guesses fail without physical verification.

Q: Can food bloggers take legal action when their recipes get scraped and copied?

A: It's murky. At least four bloggers found AI-generated copies of their entire recipe libraries—photos subtly altered, instructions lightly rephrased, republished on different domains. Because nothing is copied verbatim, traditional DMCA takedowns don't apply cleanly. The imitation is obvious but rarely actionable under current copyright law, leaving creators with few remedies.