A planned Trump–Xi summit evaporated and stocks slumped after China broadened export controls on rare earths—rules that now reach into supply chains far beyond its borders. On Friday, President Trump threatened a “massive” tariff hike and said there’s “no reason” to meet Xi at APEC in two weeks. The S&P 500 flipped from early gains and fell sharply. The Nasdaq slid more. Treasury yields dropped as investors ran for safety. Markets hate uncertainty. This is that.

What’s actually new

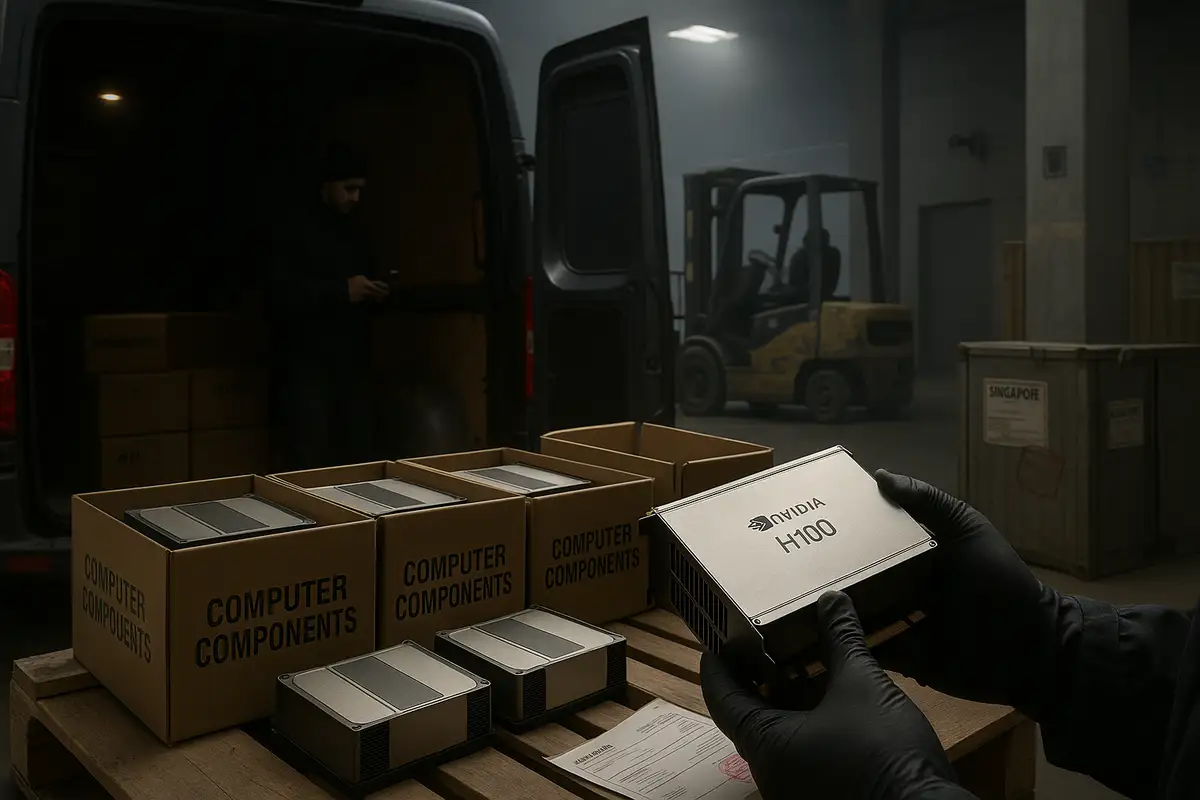

Beijing’s order requires licenses to export any product containing more than 0.1% Chinese-sourced rare earths—or made with Chinese extraction, refining, magnet-making, or recycling techniques. That second clause is the knife twist. It treats technology as jurisdiction, even when production happens in Malaysia or Vietnam. The rules take effect December 1. The message is immediate.

Key Takeaways

• Trump canceled planned APEC summit with Xi after China required licenses for any export containing 0.1% Chinese rare earths or made with Chinese technology

• China controls 90%+ of rare earth processing infrastructure—the refining bottleneck that matters more than mine deposits for semiconductors and defense systems

• Markets dropped 2% as tariff threats hit tech stocks hardest; previous May and June deals produced announcements but not sustained supply flows

• Three signals matter: December 1 enforcement strictness, whether tariff threats materialize, and if summit quietly reschedules before November ends

This is the second reset in six months. In May and June, Trump officials touted progress on rare-earth access. Companies still reported staggered flows. National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett conceded in June that releases were slower than many buyers expected. Thursday’s move widens the gate and narrows the opening. It also shows where Beijing thinks its leverage truly lies.

The processing choke point

China doesn’t just mine rare earths. It processes them. Industry estimates put China’s share of refined rare earths and rare-earth magnets above 90%. That’s the bottleneck that matters for semiconductors, EV motors, radars, and jet engines. Ore in Australia or California means little without chemical separation, metalmaking, and magnet fabrication at scale. That capacity sits mainly in China.

By tying licenses to any product using Chinese refining know-how, Beijing extends its reach past raw materials and into the playbook companies use to make them useful. A Vietnamese factory built on Chinese process IP? Under the new policy, it still needs a Chinese license to ship. That design hardens China’s position even where geography suggests diversification. It’s leverage by blueprint.

Tariffs can’t build refineries

Trump’s counter is pressure: more tariffs, possible export controls, and the claim that “for every Element that they have been able to monopolize, we have two.” Average U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods already hover around elevated levels and briefly spiked above 100% earlier this year. More hikes would sting exporters and raise costs for U.S. buyers. They won’t conjure separation plants in Ohio. Steel can be tariffed into local mills. Solvent-extraction cascades cannot.

That’s the asymmetry. Washington can tighten the screws on price and access, but the physical bottleneck is chemistry, permitting, and time. Even friendly suppliers—Australia, the U.S., parts of Southeast Asia—face multi-year buildouts to stand up refining and magnet lines at scale. Financing has improved. Environmental approvals have not. The calendar is the constraint.

Negotiations vs. physics

From Washington’s vantage point, this looks like whiplash after months of constructive talks. Trump described the relationship as “very good” and the new restrictions as a surprise. From Beijing’s, it resembles basic monopolist behavior: keep talking, offer narrowly tailored relief, maintain the structure that matters. Announcements are plentiful. Tonnage is not. That’s the pattern companies see: deals on paper, dribs and drabs in practice.

For manufacturers, the math is simple and grim. You can redesign a product around fewer rare-earth magnets. You can’t swap out decades of process control overnight. The fallback becomes inventory buffers, supplier workarounds, and political risk hedging—none of which scale well when one country holds most of the midstream.

Will the summit actually die?

The meeting may yet reappear with new choreography. Beijing never publicly confirmed it. Trump says there’s “no reason” to proceed. That ambiguity leaves room to reset without admitting a breakdown. Three near-term signals will tell the story. First, how strictly China enforces licenses after December 1—blanket rules or quiet carve-outs. Second, whether the White House follows through on “massive” tariffs or keeps them as bargaining chips. Third, the calendar—if November passes with no movement, the rift is real, not theater.

The longer game

Even if talks resume, the structural problem remains. China built the midstream over decades. That moat is deep: thousands of trained technicians, proven flow sheets, and supplier ecosystems clustered around the chemical steps competitors find hardest to replicate. Tariffs and press releases can’t shortcut that. Only investment can. It will take years.

Why this matters:

- Processing dominance—not mine output—gives Beijing durable leverage that price tools in Washington can’t quickly neutralize.

- Repeated “deals” without sustained flows signal a long stretch of managed scarcity, forcing companies to plan around uncertainty rather than certainty.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why can't the US just mine its own rare earths instead of relying on China?

A: Raw rare earth ore exists in the US, Australia, and elsewhere. The problem is processing. Turning ore into usable refined metals requires chemical separation facilities, magnet fabrication plants, and trained technicians—infrastructure China spent decades building. The US has deposits but lacks the midstream capacity to refine them at scale. Mining is easy. Chemistry is hard.

Q: How long would it take to build alternative rare earth processing capacity outside China?

A: Industry estimates suggest 5-10 years for a full-scale refining and magnet production facility, assuming immediate permitting approval and financing. Environmental reviews often add years. Building the technical workforce takes longer. Even with government support, standing up processing infrastructure that rivals China's decades of investment requires multi-year timelines. There are no quick substitutes.

Q: What does China's "technology" clause actually control?

A: Any product made using Chinese extraction, refining, magnet-making, or recycling processes now requires a Chinese export license—even if manufactured outside China. This extends Beijing's jurisdiction beyond borders. A factory in Vietnam built using Chinese chemical separation techniques needs approval to ship. It's licensing by intellectual property, not just physical materials or geography.

Q: What products would actually be affected by these export restrictions?

A: Electric vehicle motors, smartphone vibration components, wind turbine generators, jet engine components, military radar systems, guided missiles, hard disk drives, MRI machines, and high-efficiency speakers all depend on rare earth magnets. Semiconductors need rare earth compounds for polishing and doping. Petroleum refining uses rare earth catalysts. The list spans consumer electronics, defense systems, and industrial equipment.

Q: Could Trump's threatened export controls actually counter China's rare earth leverage?

A: The US dominates certain semiconductor manufacturing equipment, chip design software, and advanced computing. Export restrictions on these could pressure Beijing. But the asymmetry matters: China can replace US chips over time, while US manufacturers lack alternative rare earth processing in the near term. Tariffs raise costs but don't create supply. Export controls work best when alternatives exist. Here, they don't.