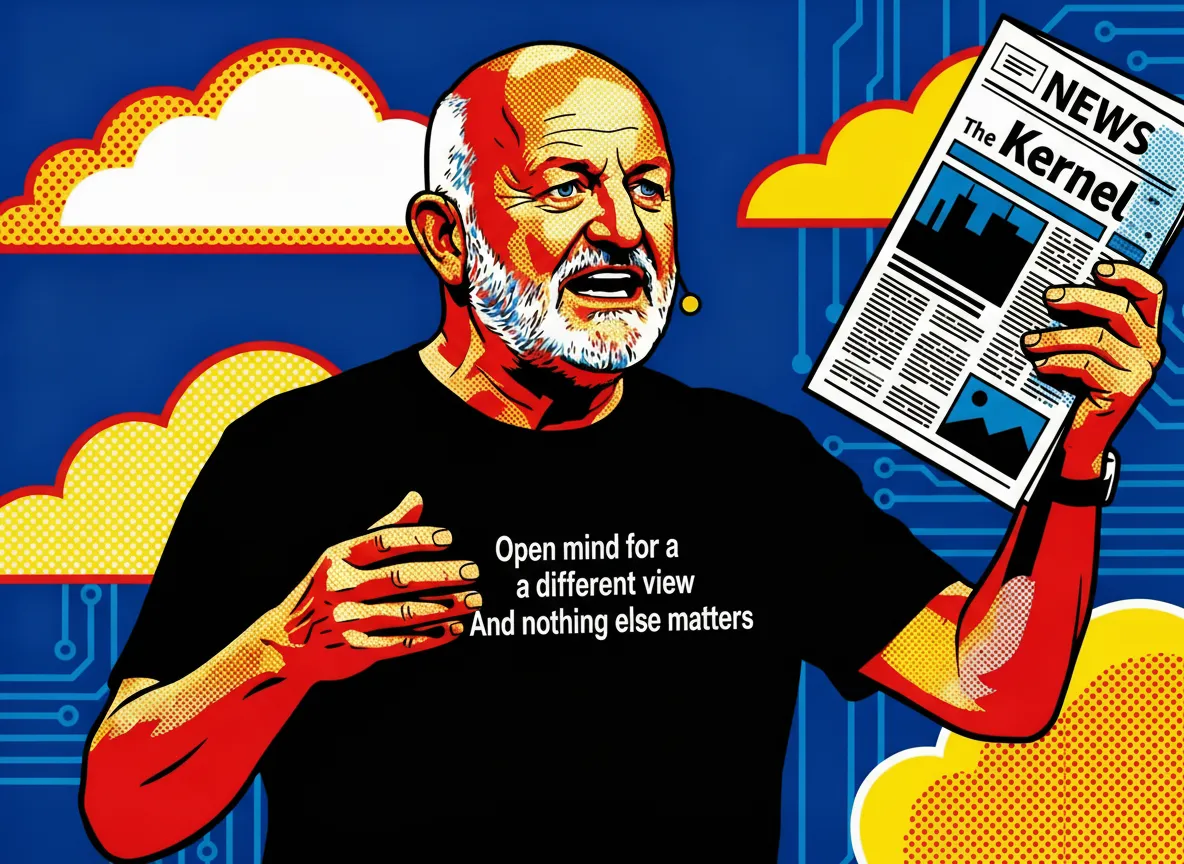

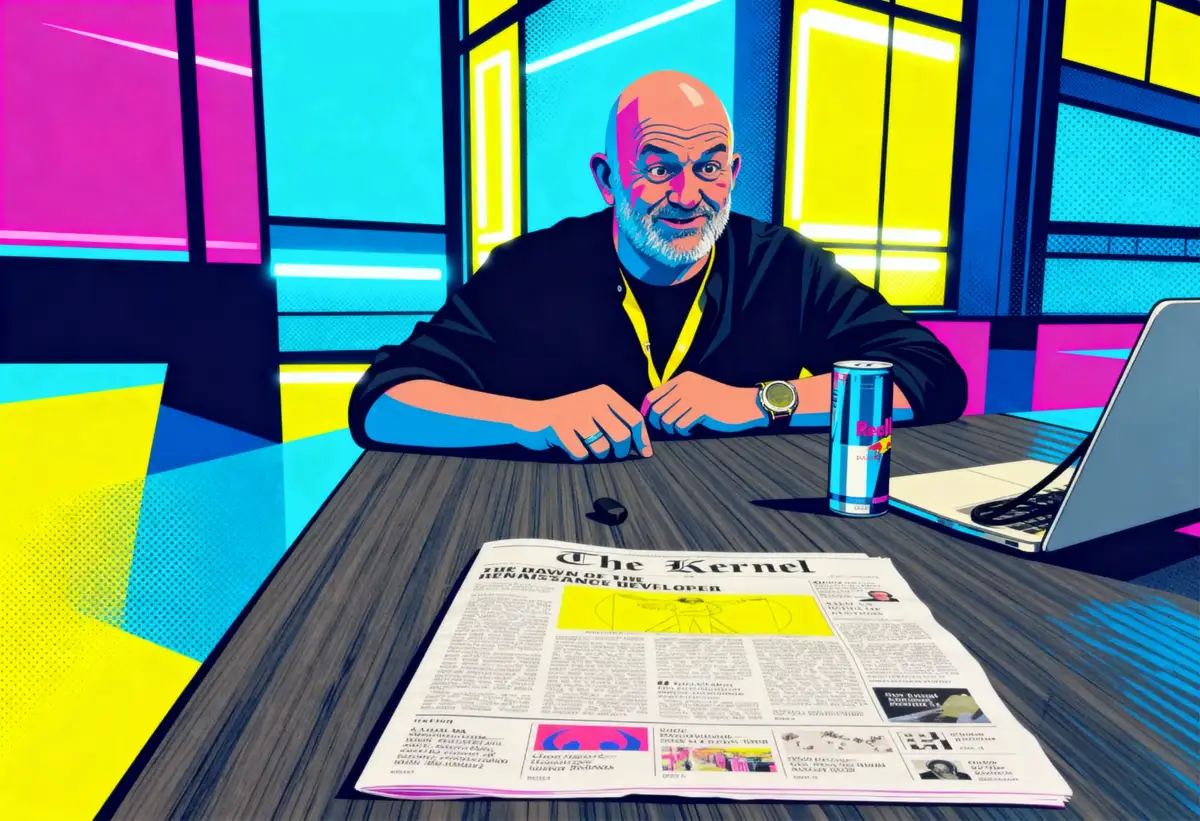

Sixty thousand people wait in the Venetian Expo. Werner Vogels walks out holding something nobody expected: a newspaper. Actual newsprint. Ink that smudges.

His black t-shirt shows Metallica lyrics. He reads them aloud: "Trust I seek and I find in you. Something new for us every day. An open mind for a different view, and nothing else matters." The 67-year-old CTO of Amazon has worn cryptic slogans on stage for fourteen years. This one fits the moment.

"The Kernel," reads the newspaper's masthead. Vogels has printed sixty thousand copies. One for every seat.

Then he addresses what he calls "the elephant in the room."

"I've been giving this keynote since 2012. That's a lot of t-shirts," he says. The crowd laughs. "But today, this streak ends. This is my final re:Invent keynote."

He pauses. "I'm not leaving Amazon or anything like that. Nobody forces me to do this." The decision, he explains, comes from wanting younger voices heard. "There are so many amazing engineers at Amazon that have great stories to tell, to teach, to help you. I think it's time for those different voices to be in front of you."

So he prints a newspaper. In 2025. The guy who helped make paper irrelevant in computing hands out something you can fold, stain with coffee, leave on an airplane seat. Open mind for a different view. Call it a parting gesture. Call it professorial. Either works.

Key Takeaways

• Vogels ends his 14-year re:Invent keynote streak to make room for younger AWS voices—but stays at Amazon as CTO

• His "Renaissance Developer" framework: be curious, think in systems, communicate precisely, own your work, become a polymath

• New term "verification debt": AI generates code faster than humans comprehend it, creating dangerous gaps before production

• Spec-driven development in Kiro IDE cuts shipping time roughly in half compared to vibe coding alone

From X-Rays to Everything Store

Vogels took a strange path to tech royalty. Dutch navy service. Medical radiology. Computer science came later, almost sideways. He earned his Ph.D. from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in 2003—his advisor was Andy Tanenbaum, whose operating systems textbook trained half the engineers in Silicon Valley. Vogels specialized in distributed computing: making scattered machines behave as one.

That expertise turned out to matter. Amazon in 2004 was buckling. The company had built itself selling books and DVDs, and its software architecture showed it. Holiday traffic crushed the servers. Something had to change.

Vogels arrived as Director of Systems Research. Months later: CTO. The speed of that promotion tells you what Amazon saw in him.

What followed reshaped how software gets built. Vogels and his team broke Amazon's monolithic codebase into hundreds of small services. Each team owned its piece completely. Wrote the code, ran the servers, answered the pager at 3 a.m. when something broke.

"You build it, you run it." Five words. They demolished the wall separating developers from operations in traditional IT shops. That wall had stood for decades. Vogels tore it down. The DevOps movement traces back to what Amazon figured out in those years.

Then the insight that birthed an industry. Amazon had built infrastructure capable of handling Black Friday traffic spikes. Most of the year, that capacity sat idle. Why not rent it?

AWS launched in 2006. Two services: S3 for storage, EC2 for computing power. Vogels called S3 "the ninth world wonder in a digital sense." Critics called AWS a distraction from retail. A side project. Nice revenue, maybe, but not the main event.

Around 2010, Vogels predicted AWS would eventually exceed Amazon's retail business. People thought he'd lost perspective. A cloud computing division bigger than the everything store?

He was right. AWS now holds roughly 30% of the global cloud infrastructure market. Microsoft trails at 22%, Google at 12%. AWS generates the bulk of Amazon's operating profits. Every major tech company scrambled to build competing cloud platforms after watching Amazon's runaway success.

Vogels saw it coming when nobody else did.

The Renaissance Developer

The keynote's core message lands differently than expected. No major product announcements. Instead, Vogels offers a framework he calls "the Renaissance developer"—five qualities he believes engineers need in the AI era.

He draws the parallel explicitly. The Renaissance came after darkness—plague, death, the Middle Ages. What sparked the rebirth? Curiosity. And tools evolved alongside the curious: the pencil, the vanishing point in painting, the microscope, the telescope, the printing press.

"It was a time where art and science were part of the same conversation," Vogels says. "Creativity and technology evolved together."

The five qualities: Be curious. Think in systems. Communicate with precision. Own what you build. Become a polymath.

That last one requires explanation. Polymath comes from the Greek "manthanein"—to learn. Nothing to do with mathematics. Da Vinci exemplified it: painter, engineer, anatomist, inventor. Vogels doesn't expect everyone to become Da Vinci. But he wants developers shaped like the letter T—deep expertise in one domain, broad knowledge spanning many.

"Great developers are T-shaped," he says. "They're experts in their field who understand how their work fits into a larger system. You must broaden your T."

"The Work Is Yours, Not the Tools"

For someone who built infrastructure enabling the AI boom, Vogels spends considerable stage time warning about its misuse. One phrase recurs throughout the keynote: "The work is yours, not the tools."

He coins a term: verification debt. AI generates code faster than humans can comprehend it. The gap between generation and understanding allows software to reach production before anyone validates what it actually does.

"Vibe coding is fine," Vogels says, "but only if you pay close attention to what is being built. We can't just pull a lever on your IDE and hope that something good comes out."

He pauses. "That's not software engineering. That's gambling."

The solution he presents involves specifications—documents that reduce the ambiguity of natural language before AI generates code. Claire Legory, senior principal developer on the Kiro team, demonstrates their new IDE built around this concept. Spec-driven development, they call it. Requirements, then designs, then tasks—each refined before code generation begins.

"With vibe coding, the AI takes its best guess at what you meant," Legory explains. "With spec-driven development, you refine what you mean through specs before the code arrives."

Vogels also pushes hard on code reviews. In an AI world, he argues, they matter more than ever.

"I encourage all of you to continue and increase your human-to-human code reviews," he says. "When senior and junior engineers work through code together, it becomes one of the most effective learning mechanisms we have. AI will change many things, but the craft is still learned person to person."

"I Drift Off"

Earlier in the week, in a side room at re:Invent, Vogels sat down with implicator.ai. The conversation careened. Healthcare. Loneliness. Japanese eldercare. Kenyan teenagers. Cultural homogenization in AI. His hands moved constantly. One thought crashed into the next before the first one finished.

"I have a tendency to drift off," he said at one point, catching himself mid-tangent. No apology in his voice. The drifting is how he thinks.

The tangent that prompted the admission: stroke detection. A neurosurgeon in Dublin told him something that lodged in his brain. Every minute a major stroke goes undetected costs a million brain cells. Die. Gone. The math haunted Vogels.

So he started calculating. CT scans could run through language models to catch strokes faster. But which model? The big Claude model runs $15 per million tokens. Facebook's smallest Llama? Fifteen cents.

"Is the answer you get from that big model so much better?" Vogels asked. For stroke detection, maybe not. "If the only thing you want to do is word completion, you don't want to pay $15 per word."

Here's where it gets concrete. At $30 per scan, hospital administrators hesitate. They run cost-benefit analyses. They form committees. Meanwhile, brain cells die. Drop the cost to 20 cents? Scan everyone who walks in with a headache. The economics determine the medicine.

The Loneliness Problem

His predictions for the coming years veer toward the unexpected. Not new cloud services. Human problems.

Loneliness fixates him. He calls it an epidemic nobody recognizes as one.

"Baby boomers—and I'm sort of the last of that generation, now you can kind of guess how old I am—they're all healthy. Healthier than generations before. They have disposable incomes. The longer we can keep them at home, the lower the stress on healthcare systems."

He visited Japan recently. The traditional model there: kids care for aging parents, everyone lives together, grandparents help raise grandchildren. That model is cracking. Younger generations want careers. They don't want to become caretakers.

Technology might fill part of the gap. Vogels rattles off examples. Pressure sensors in beds—if grandma goes to the bathroom at night and doesn't come back in ten minutes, an alarm triggers. Sounds trivial. But without that sensor, she might need to move to a care facility just so someone can check on her. Robots that remind patients about medication. Amazon's Astro home robot, which users apparently treat less like an appliance and more like... something else.

He mentions Kate Darling, the MIT researcher who studies how humans relate to robots. The findings surprised him. People don't treat robots like machines. They treat them like pets. Give them names. Talk to them. Play with them.

"And not if they're six or seven or eight years old," Vogels said. "No. If they're 80, 90 years old. And if you make one that looks like a cat and meows like a cat—you'll sell a lot of them."

Does a robot cat solve loneliness? He doesn't pretend it does.

"Loneliness is mostly solved by human to human. Unfortunately."

That last word hung there. Unfortunately. Because human connection can't scale. Can't be manufactured. Can't be deployed across populations.

His own family scattered across the globe. One daughter in Florida. One in Washington State. Vogels in Dubai. "And by the way, I wouldn't want them to take care of me, but that's a whole different story." He laughed when he said it. The laugh didn't erase the point.

"I Don't Want the World to Turn Into America"

In that same conversation, Vogels leaned forward when the topic shifted to language models. His energy changed.

The biggest, most capable AI models come from two places: America and China. Translation handles the language barrier on the surface. Ask a question in Spanish, get an answer in Spanish. The words convert fine.

Culture doesn't convert.

Vogels used an example. Ask an American-trained model to summarize an Isabel Allende novel. Compare that to what you'd get from a model trained on South American literature with South American cultural context. The facts might match. The understanding won't.

"Culture is super important in communication," he insisted. "It's not only how big the models are. How much reasoning can they do? But what's the core of their culture?"

He pointed to Ricoh in Japan. They trained language models from scratch on Japanese documentation, specifically to interact with Japanese customers appropriately. An American model translated into Japanese gets the information right and the social register wrong. The politeness levels. The formality markers. The thousand small signals that Japanese speakers read automatically.

Then there's Jacaranda Health. They work with pregnant women in Kenya, mostly through SMS. Not smartphone apps—basic text messages on basic phones. The women they serve are young. Fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years old. Pregnant. Often scared.

Think about that for a second. A chatbot built for European users assumes a certain demographic. Late twenties, early thirties. Educated. Married, probably. The whole communication style follows from those assumptions.

Now try deploying that in rural Kenya. A teenager gets medical advice delivered in a tone meant for someone twice her age, from a different continent, with a different relationship to authority and healthcare and pregnancy itself. The information might be accurate. She won't act on it. The delivery kills the message.

Jacaranda built something different. Local languages. Local cultural knowledge baked in. Communication that actually reaches the people receiving it.

"I don't want the world to turn into America," Vogels said. No hedging. No diplomatic softening.

Rwanda, Nairobi, the Amazon

His keynote draws heavily on two month-long trips this year—one to Sub-Saharan Africa, one to Latin America. The travels inform his optimism about technology applied to hard problems.

In Rwanda, the Ministry of Health operates something that stopped him cold. Their Health Intelligence Center displays near real-time data from healthcare facilities across the entire country on massive screens. Disease outbreaks. Maternal health outcomes. Policy decisions driven by actual data.

"They've created this model which shows which parts of the country are more than a 30-minute walk away from a healthcare provider," Vogels tells the keynote audience. "And they use this data to strategically place new maternal health facilities in underserved areas. They use data to drive policy and to actually implement that policy."

In Nairobi, he met a startup called Coco Networks attacking a problem most Westerners never consider. In poorer areas, people borrow a dollar or two in the morning, buy goods, sell them on the street, return the money in the evening, and keep 40 or 50 cents profit. Enough for food. Not enough for cooking fuel. So they burn carbon. Massive pollution.

Coco built ATM-like machines dispensing ethanol in small canisters. Walk up, plug in your canister, buy five cents of gas. Enough to cook dinner.

"This is what happens when developers apply their skills to real human challenges," Vogels says.

On the Amazon river, he visited a beverage company called Groek bij Aker that gives young people economic futures so they don't abandon their villages for cities. He saw pink dolphins. It took him 21 years at Amazon to finally reach the river that shares the company's name.

The Newspaper on Your Seat

Back on stage, Vogels works through his framework. Be curious. Think in systems. Communicate. Own your work. Broaden your T.

"The Kernel" sits in sixty thousand laps. The format forces different engagement than slides. You hold it. Turn pages. Read linearly instead of skimming bullet points. There's an article by Andy Warfield about stress and learning that Vogels urges everyone to read.

The choice feels intentional. Vogels spent fourteen years explaining cloud computing to audiences wanting quick takeaways. He gave them something richer—a philosophy of building systems that scale, principles outlasting any individual product.

"You build it, you run it." "APIs are forever." "Eventually consistent." These phrases entered industry vocabulary because Vogels repeated them until they stuck.

Now newspapers. In a world drowning in ephemeral digital content, he prints something physical. Something you take home. Something requiring no login.

The Man From Amsterdam

One detail about Vogels: he didn't get a driver's license until age 28. Growing up in Amsterdam, he didn't need one. Bicycle. Tram. Train. That was transportation.

The detail illuminates his worldview. He comes from somewhere public infrastructure works, where cars are optional, where density enables efficiency. When he criticizes American assumptions baked into AI models, he speaks from outside the American frame.

"If Elon is right, tunnels are the answer," Vogels mused about urban transportation in our conversation. "Others think flying taxis will work. Next month in Dubai, the first ones launch. 350 dirhams—about 90 euros—from the airport to Dubai Marina."

He ran the comparison. Driving that route: ninety minutes. Flying: a few minutes. Worth 400 dirhams?

But his instinct pulled elsewhere. "I'd solve it with better public transportation. Because I'm from Amsterdam."

The city shaped the engineer. The engineer shaped the cloud. The cloud shapes everything.

Pride in the Unseen

As the keynote closes, Vogels turns reflective. He talks about the work nobody sees. Database engineers maintaining systems that stay up all night. Clean deployments. Rollbacks nobody notices.

"Your customers are never going to tell you that your database engineers are doing amazing work," he says. "Only you understand the work that goes into it."

Professional pride, he argues, defines the best builders. Doing things properly even when nobody's watching.

"When I look at the work that you deliver every day, I see that commitment everywhere. For that, I am immensely proud of you. Thank you for all that you do."

He pauses. Grins.

"Two more words."

The crowd waits.

"Werner out."

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Who is Andy Tanenbaum, Vogels' PhD advisor?

A: Andrew Tanenbaum is a Dutch-American computer scientist whose textbooks on operating systems and networks trained generations of software engineers. He created MINIX, an educational operating system that directly inspired Linus Torvalds to build Linux. Studying under Tanenbaum gave Vogels deep expertise in distributed systems—the foundation of everything AWS became.

Q: What does "eventually consistent" mean and why does it matter?

A: Traditional databases guarantee all users see identical data instantly. Eventually consistent systems accept brief delays—your shopping cart might take a few seconds to sync across servers. The tradeoff: much faster performance and higher availability. Vogels championed this approach at Amazon, and it became standard in cloud databases like DynamoDB, Cassandra, and MongoDB.

Q: Why did Werner Vogels move to Dubai?

A: Vogels hasn't publicly detailed his reasons, but Dubai has become a hub for tech executives seeking tax advantages and proximity to emerging markets in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The city also serves as a testbed for new technologies—Vogels mentions flying taxis launching there next month at 350 dirhams per trip.

Q: What is the Dynamo paper Vogels co-authored?

A: Published in 2007, the Dynamo paper described Amazon's internal key-value storage system designed for extreme reliability. It introduced techniques for spreading data across servers while tolerating failures. The paper became a blueprint for an entire generation of NoSQL databases—engineers at LinkedIn, Facebook, and others cited it when building Kafka, Cassandra, and similar systems.

Q: What is Amazon Bedrock that Vogels mentions?

A: Bedrock is AWS's platform for accessing multiple AI models through a single interface. Instead of committing to one provider, companies can experiment with models from Anthropic, Meta, Mistral, and others. Vogels built it for cost comparison—testing whether a 15-cent model works as well as a $15 model for specific tasks before scaling up spending.