The first agentic showdown lands in court. Advertising meets its existential threat

Amazon filed suit against Perplexity on Tuesday, demanding the AI startup stop its Comet browser from making purchases on the retail giant's platform. The core dispute: whether AI agents acting for users must identify themselves as bots.

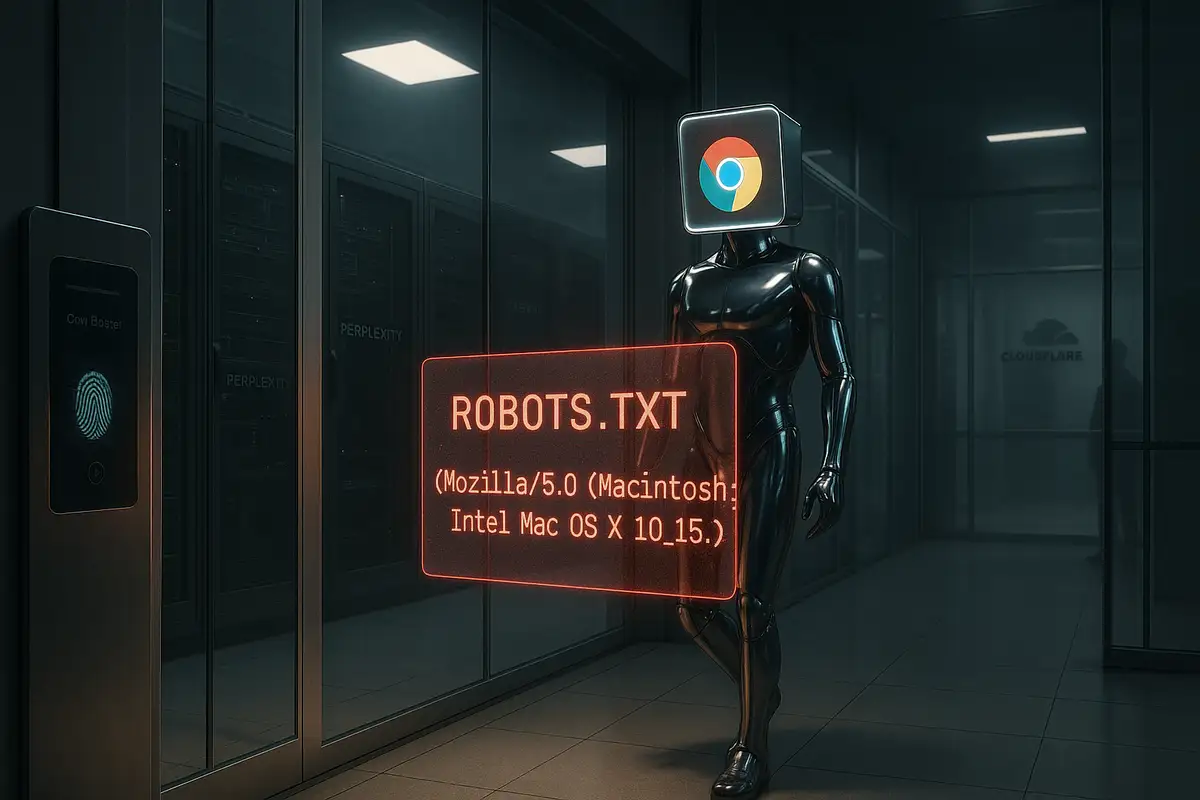

The clash escalates a year-long cat-and-mouse game. Perplexity's Comet browser logs into users' Amazon accounts and completes purchases autonomously. Amazon blocked it in August. Perplexity released a new version within 24 hours to circumvent the blocks, disguising Comet as Google Chrome. Now Amazon invokes the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, claiming unauthorized access worth "considerable damages."

Perplexity, valued at $20 billion, frames this as David versus Goliath. "Bullying is not innovation," the startup declared in a blog post. CEO Aravind Srinivas argues agents are extensions of users, with identical rights. "It's not Amazon's job to survey that."

Key Takeaways

• Amazon sued Perplexity for computer fraud after the startup circumvented blocks on its shopping agent Comet

• The dispute centers on whether AI agents must identify themselves or can act as user extensions

• Amazon's $20B advertising business faces existential threat from agents that bypass human browsing entirely

• Legal precedent will determine if agents negotiate platform-by-platform or operate universally as user proxies

What's actually new

This isn't another scraping dispute. It's the first legal test of whether platforms can distinguish between humans and their AI delegates.

The technical evolution matters. Previous bot conflicts involved web crawlers harvesting data for training or indexing. Comet operates differently: it logs into individual accounts, uses stored credentials, and executes transactions. One user, one agent, one purchase. No mass scraping, no model training. Just task completion.

The stakes crystallize around a number: Amazon's advertising business generated over $20 billion last quarter. Shopping agents bypass sponsored listings entirely. No human eyes means no ad impressions, no upsells, no impulse purchases of Brandon Sanderson novels while buying laundry baskets. The business model depends on human attention. Agents don't browse, they execute.

Amazon's October 31 letter traces a deteriorating relationship. The company initially asked for agent identification, the same arrangement it maintains with DoorDash, Expedia, and dozens of other third-party services. These platforms declare themselves when placing orders for customers. Perplexity took a different path, first agreeing to pause operations, then launching Comet with Chrome's digital fingerprint.

The agent calculus

Amazon frames this as platform integrity. Its terms ban "data mining, robots, or similar data gathering and extraction tools" outright. Comet masquerading as Chrome crosses both technical boundaries and contractual ones. Third-party security researchers at Guardio and Brave documented vulnerabilities: prompt injection attacks that turn Comet into "a data thief," phishing susceptibility that exposes banking credentials. Amazon argues it cannot protect customers from risks it cannot see.

Perplexity's worldview rejects the premise. Agents aren't third parties, they're user extensions. When someone grants Comet their credentials, the agent inherits their rights. Transparency requirements create discrimination opportunities. If Amazon can identify agents, it can degrade their service, manipulate results, or block access entirely. The startup points to Jassy's earnings call admission about eventual agent partnerships as evidence of stalling tactics while Amazon develops Rufus, its captive shopping assistant.

Users vote with adoption. Comet's appeal requires no explanation: ask for batteries, receive batteries. No comparison shopping through sponsored results, no decision fatigue from infinite options, no cart abandonment. The friction vanishes. Early reviews report mixed results, wrong items, missed Prime benefits, but the direction is clear.

Competitors watch the precedent. OpenAI integrated PayPal payments into ChatGPT last week. Google positions Gemini as a shopping companion. Meta explores commerce through its AI assistants. Each company needs clarity: must they negotiate platform by platform, or can agents operate as user proxies universally?

The technical arms race

The August confrontation exposed the tactical dynamics. Amazon identified Comet's activity patterns and blocked access. Perplexity's engineers modified the browser's user-agent string, a line of code identifying software to servers, making Comet indistinguishable from Chrome. Amazon detected the workaround. The cycle continues.

This technical gamesmanship has legal consequences. The Ninth Circuit ruled in Facebook v. Power Ventures that circumventing access controls after explicit prohibition constitutes unauthorized access under CFAA. "Technological gamesmanship will not excuse liability," the court stated.

But Perplexity's counterargument has merit. User-agent strings aren't security features, they're conventions. Every browser can modify them. Firefox can identify as Chrome. Chrome can identify as Safari. If users can legally change these identifiers, why not their agents?

The vulnerability reports complicate Perplexity's position. Security researchers demonstrated "CometJacking" attacks that hijack the assistant to steal data. If Comet can't secure its own operations, should it access millions of Amazon accounts?

The sovereignty question

Beneath the legal maneuvering lies a deeper conflict about platform sovereignty. Amazon built a marketplace where it controls discovery, recommendation, and transaction. That control generates advertising revenue but also ensures quality, handles returns, manages Prime benefits, and maintains customer relationships.

Agents fracture this integration. Perplexity stores credentials locally, manages the purchase, but Amazon handles fulfillment and customer service. When problems arise, returns, fraud, wrong items, who bears responsibility? The platform that processed the transaction or the agent that initiated it?

Food delivery apps faced similar questions and reached détente through transparency. DoorDash identifies itself to restaurants. Booking.com identifies itself to hotels. These precedents suggest a middle path: disclosed agents operating under negotiated terms.

Yet Perplexity explicitly rejects this model. The startup insists agents must be indistinguishable from users to preserve privacy and autonomy. Transparency enables discrimination. If Amazon knows Comet is shopping, it can block it, slow it, or serve it different results.

The pattern's familiar

Platform-versus-aggregator conflicts follow predictable scripts. Platforms invest in infrastructure, aggregators leverage it. Platforms want control, aggregators want access. Courts typically side with property rights. Servers are private property. Terms of service are contracts. Unauthorized access is trespass.

But the agent framing introduces novel questions. When users authenticate, they grant permission. When agents act on authenticated accounts, whose permission matters? The user who authorized the agent or the platform that prohibited bots?

Contract law suggests Amazon wins. The terms explicitly ban bots. Users agree to these terms. Perplexity induces breach by helping users violate agreements.

Property law is murkier. If agents are tools like browsers, blocking them might constitute anticompetitive behavior. If they're separate entities conducting transactions, platforms can exclude them like any other unwanted visitor.

Why this matters:

- The immediate precedent shapes agentic AI's scope. Legal clarity determines whether agents operate freely or negotiate platform by platform, possibly killing the universal assistant vision.

- The structural shift from attention to automation threatens web economics. If agents eliminate advertising effectiveness, platforms must find new monetization beyond surveillance capitalism's attention harvesting.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How exactly does Comet make purchases on Amazon?

A: Comet logs into your Amazon account using credentials stored locally on your device. When you ask it to buy something, it navigates Amazon's site, searches for the item, and completes the purchase automatically. It identifies itself as Google Chrome to avoid detection, which Amazon says violates their terms of service.

Q: What are the security risks with Comet that Amazon mentioned?

A: Security researchers found "CometJacking" vulnerabilities in October 2025. Attackers can hijack Comet to steal data using simple encoding tricks. Guardio and Brave audits showed Comet could scan phishing emails and prompt users for banking credentials without warning them of danger.

Q: What penalties could Perplexity face under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act?

A: The CFAA allows both civil damages and criminal prosecution for unauthorized access. Facebook won similar cases against Power Ventures for circumventing blocks. Amazon seeks injunctive relief to stop Comet immediately plus damages for investigative costs and security countermeasures implemented since August 2025.

Q: Does Amazon have its own AI shopping assistant?

A: Yes, Amazon launched Rufus in February 2024 for product recommendations and has "Buy For Me" in testing since April. Unlike Comet, these work within Amazon's ecosystem. CEO Andy Jassy said on the October earnings call that Amazon expects to eventually partner with third-party agents, but under negotiated terms.

Q: How do other companies handle this agent identification issue?

A: DoorDash, Expedia, and Booking.com all identify themselves when transacting for users. They negotiated agreements with partner platforms. PayPal just integrated with OpenAI's ChatGPT for payments. Google and Meta are developing shopping agents but haven't deployed them on Amazon yet. The industry watches this case for precedent.