Meta bought a Chinese AI startup. Now three government agencies are fighting over what to do about it.

Key Takeaways

• Meta acquired Manus for $2B after the Chinese-founded AI startup relocated to Singapore, a strategy insiders call "China shedding"

• Three Chinese agencies disagree on whether the deal violates technology export laws; a formal investigation could last a year

• U.S. national security hawks separately argue the VC backing violated outbound investment rules banning AI deals with China

• The controversy is already chilling venture capital investment in Chinese AI startups seeking foreign exits

The Singapore Shuffle

If you're an AI founder in Shenzhen right now, you've memorized this sequence. Last summer, a team of engineers in Beijing and Wuhan packed up their AI agent project and moved to Singapore. The company was called Manus. It built an assistant that could handle market research, write code, and run data analysis with limited human supervision. By December it claimed $100 million in annual recurring revenue. By January, Meta had agreed to pay two billion dollars to acquire it.

The sequence looked almost too clean. Build in China, relocate to a country without the geopolitical baggage, collect a fat American check. Tech industry insiders in China started calling this maneuver "China shedding," the practice of stripping away Chinese roots to make a company palatable to Western investors and acquirers.

Kevin Xu, founder of U.S.-based Interconnected Capital, put it plainly. "Manus is the first successful exit of China shedding for a start-up," he told the New York Times. Other founders watched. Some took notes.

Then Beijing panicked.

Three Agencies, Three Opinions

China's commerce ministry announced in early January that it was reviewing whether Meta's acquisition violated the country's technology export laws. The Financial Times reported that the review was triggered at the highest levels of government, where officials invoked a specific fear: "selling young crops," a euphemism for letting emerging technologies leave the country before they mature.

What followed was unusual, and visibly anxious. Three separate agencies convened meetings to discuss a single startup acquisition. The commerce ministry, defensive about enforcement gaps in its export controls, focused on legal violations. The State Administration for Market Regulation examined antitrust angles. And the National Development and Reform Commission, the economic planner driving China's tech ambitions, weighed in on strategic value.

They couldn't agree. The NDRC had waved Manus through when the company first relocated to Singapore months earlier, apparently unbothered. Now the commerce ministry was treating the same move as a national security breach. Chinese media had already labeled the departing staff "defectors." Someone in the bureaucracy had been asleep. Nobody wanted to admit who.

This disagreement tells you something about where China's tech governance stands right now. Officials want tighter oversight. They also want to encourage the kind of innovation that produces companies like Manus in the first place. Those two impulses are pulling in opposite directions, and the agencies know it.

Join 10,000+ AI professionals

The geopolitics of AI, covered from San Francisco. Who's building, who's buying, and which governments are scrambling to keep up. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The Benchmark Problem

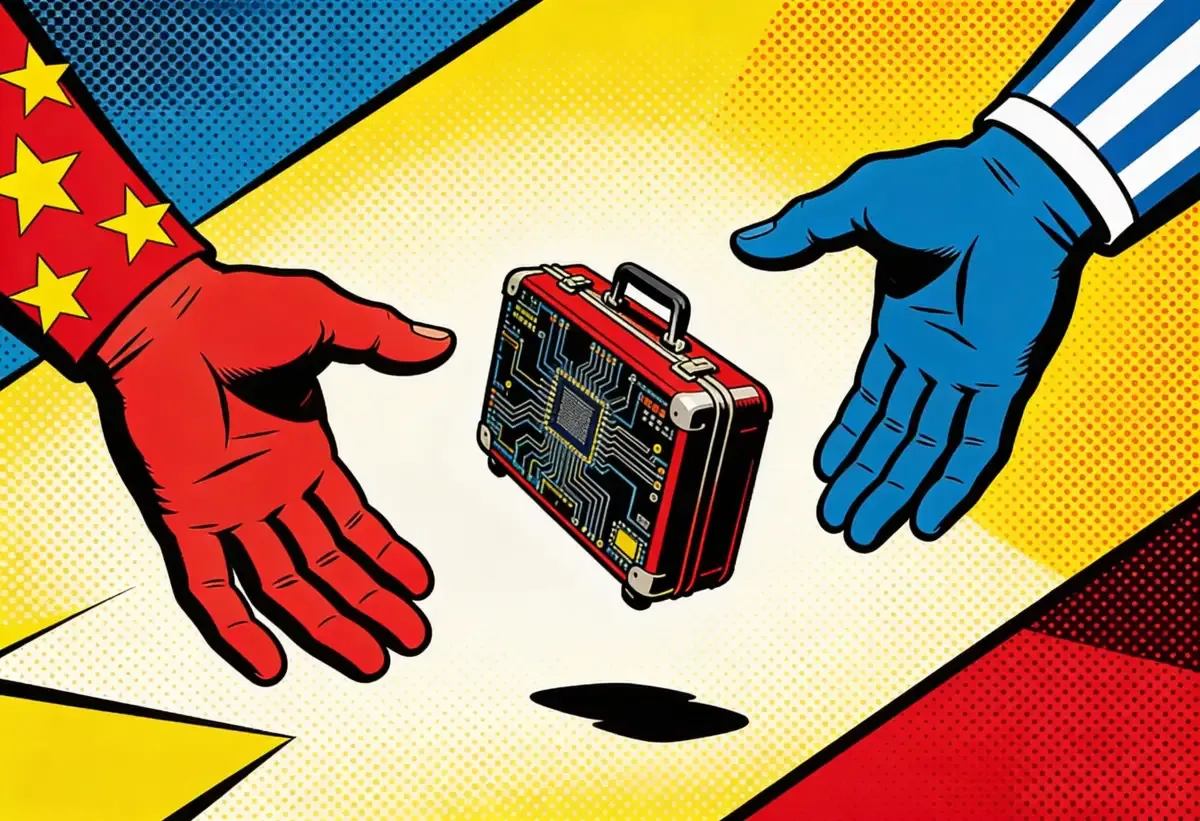

The deal also drew fire in Washington, though from the opposite direction. National security hawks were furious that Benchmark, the Silicon Valley venture capital firm that backed Manus before the Meta acquisition, had apparently violated rules barring U.S. investors from funding Chinese AI companies.

Manus had moved to Singapore. It blocked Chinese users from accessing its products. On paper, it wasn't a Chinese company anymore. But its founders were Chinese engineers who'd been writing code in a Wuhan office six months earlier. Its technology was prototyped in Beijing. The question of where a company "is" becomes slippery when the intellectual property travels in a laptop bag across the Causeway.

This is the bind. American regulations say you can't invest in Chinese AI. Chinese regulations say you can't export Chinese tech. Manus tried to thread both needles by existing in neither jurisdiction fully. For a few weeks, that looked brilliant. Now it looks like a case study in how both superpowers get played.

The Involution Engine

Understanding why engineers would flee China for Singapore requires understanding what they're fleeing from. The Chinese economy is running a fever that economists there call "involution," a state of brutal internal competition where companies fight over shrinking returns.

The property market collapse left consumers sitting on their wallets. Food delivery, electric vehicles, e-commerce, every sector churns with startups willing to operate at a loss for years just to suffocate competitors. Meituan, the delivery giant, burned cash in China for nearly a decade before turning profitable. It's now spending a billion dollars to replicate the same playbook in Brazil.

Jianggan Li, chief executive of consultancy Momentum Works in Singapore, described the calculus for Chinese entrepreneurs. "When you build a business outside China, you are able to have better margins and to sleep more easily."

Better margins and better sleep. That's what two billion dollars buys when you're building AI agents in Wuhan and your competitors are willing to work for free.

The Impossible Bind

Linghao Bao, a senior analyst at Trivium China, named the trap Beijing built for itself. "Beijing will certainly want to send the message that Chinese-born tech companies must honour certain responsibilities to the state and the Chinese people," he said. But crack down too hard and you scare off the capital. Bao warned of Beijing "overplaying its hand," spooking the same investors that Chinese policymakers have spent years trying to attract.

Bao is being diplomatic. The situation is worse than he describes. Venture capital investors were nervous, and said so openly to the Financial Times. Manus had presented a model. Relocate, shed the Chinese identity, attract foreign capital, exit at a premium valuation. If Beijing blocks this path, the money stays away. If Beijing permits it, the talent drains faster. There's no version where both problems get solved.

Daily at 6am PST

Don't miss tomorrow's analysis

AI geopolitics, acquisition strategy, and regulatory fault lines. Covered daily from San Francisco for executives who need the full picture.

Free. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

One China-based investor managing U.S. dollar funds described the mood in a tone closer to resignation than caution. "Fundraising from foreign investors only started to warm up last year. Now investors are being told there could be a ban on this type of deal. Who would dare to go big on China AI investments under uncertainties?"

Another investor said the review was already making Chinese startups reconsider the Singapore reincorporation strategy. "One lesson learned is to stay as low profile as possible." The playbook works. You just can't talk about it.

The Precedent Machine

The TikTok restructuring, finalized the same week as the Manus controversy, adds another layer. ByteDance agreed to license its recommendation algorithm to a new U.S.-based joint venture, retaining a 19.9% stake while surrendering operational control. Kevin Xu sees this arrangement opening doors. Battery technology, rare earth metals, other segments where Chinese companies dominate, all could flow through similar licensing structures.

But each deal tests a different boundary. TikTok's algorithm will be retrained on American data alone. Manus's AI agents were built with Chinese engineering talent sitting in rooms in Beijing and Wuhan, not sitting on servers you can relocate with a contract. The question isn't about data sovereignty anymore. It's about whether intellectual labor can be separated from national identity the way a server rack can be moved from one country to another.

China amended its technology export rules in 2020 specifically to give the government veto power over deals like TikTok's. Those same rules now apply to Manus. Any formal investigation could last up to a year. By then the engineers will have been Meta employees for eighteen months, building on American infrastructure with American capital. The investigation is an autopsy on a patient who already left the hospital.

What Gets Built Next

The engineers who built Manus are now Meta employees in Singapore, a long way from the Wuhan labs where the first prototypes ran. Their AI agent handles market research and coding tasks, the kind of work that scales fast when attached to Meta's distribution network and two billion dollars in backing.

For China's policymakers, the uncomfortable question isn't whether Manus was worth two billion. It's what the next Manus is worth, and whether its founders are already booking flights to Changi Airport. The "China shedding" playbook is public now. Every ambitious AI team in Shenzhen and Hangzhou knows the steps. Relocate. Block Chinese users. Raise from American VCs. Wait for the acquisition offer.

Beijing cannot stop this. Not without strangling the startup ecosystem it spent a decade building. The conditions that produced Manus, the involution at home, the capital abroad, the talent caught between two governments claiming jurisdiction over the same lines of code, those conditions are structural. Three agencies can hold all the meetings they want. The next exit strategy is already being sketched on a whiteboard somewhere. No press releases this time. No celebration quotes in the New York Times. Just quietly.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is Manus and what does it do?

A: Manus is an AI agent startup founded by Chinese engineers in Beijing and Wuhan. Its product handles market research, coding, and data analysis with limited human supervision. The company drew attention in March 2025 when it launched an agent that could build websites and perform basic coding tasks. By December it claimed $100 million in annual recurring revenue.

Q: What is "China shedding"?

A: "China shedding" is the practice of Chinese tech companies stripping away their Chinese identity to attract Western investors. Steps include relocating headquarters to Singapore, blocking Chinese users from the product, and raising capital from American venture firms. The term emerged after Manus successfully used this approach to secure a $2 billion acquisition by Meta.

Q: Why are three Chinese agencies reviewing the deal?

A: The commerce ministry is examining whether export control laws were broken. The State Administration for Market Regulation is looking at antitrust angles. The National Development and Reform Commission is weighing the strategic value of the technology. The three agencies have different views on the importance of Manus's technology and its Singapore relocation.

Q: How do China's technology export rules apply here?

A: In 2020, China amended its export control rules to cover a range of software technologies. These amendments were originally designed to give Beijing veto power over the TikTok deal. The same rules now apply to Manus's AI agent technology. Any formal investigation could last up to a year, though enforcement is complicated by the team's relocation to Singapore.

Q: What does this mean for other Chinese AI startups?

A: The Manus review is already making Chinese startups think twice about the Singapore reincorporation strategy. Venture capital investors told the Financial Times that uncertainty around potential bans is chilling investment. One investor said the lesson is to "stay as low profile as possible," suggesting future attempts will be quieter but not necessarily fewer.

Related Stories