Pieter Maes gave Claude Code access to 100 non-fiction books, a handful of debugging tools, and a single instruction: "find something interesting."

What came back was a trail linking Steve Jobs's reality distortion field to Theranos's faked demos to Peter Thiel's observation that successful startups resemble cults to Eric Hoffer's 1951 analysis of charlatanism in mass movements. Four books. One thread. The connection held.

Most people use AI to compress books. Summarize this PDF. Give me the bullet points. Maes did the opposite. He wanted connections, not condensation. His system doesn't shrink books down. It wanders across them, hunting for the moment when one author's argument accidentally extends another's.

The Breakdown

• Developer Pieter Maes used Claude Code with CLI tools to find thematic connections across 100 non-fiction books, spending roughly £10 on processing.

• An agent with simple tools outperformed a hand-tuned pipeline. The pipeline returned predictable results; the agent surprised him.

• The real value wasn't generation or summarization. It was cheap revision, the ability to change decisions without starting over.

• Risk: systems optimized to find connections will find them, whether or not those connections exist outside the model.

The pipeline that lost

The project started as you'd expect. Maes constructed a pipeline, chaining LLM calls together, hand-tuning prompts, assembling context at each stage. The architecture was clean. The results weren't.

"I was mainly getting back the insight that I was baking into the prompts," he wrote. If his prompt mentioned "leadership," the pipeline surfaced passages about leadership. The connections were correct but predictable, the kind of thing you could have guessed without running the system at all. Nothing surprised him.

Then he tried something looser. He gave Claude access to his debugging CLI tools, the ones he'd built for himself, and let it wander. No orchestration. No carefully staged context. Just tools and a vague direction.

Claude wiped the floor with the pipeline.

The agent inferred what information it needed, pulled in relevant context, and made connections the hand-tuned system missed. "It was a clear improvement to push as much of the work into the agent's loop as possible."

Daily at 6am PST

The AI news your competitors read first

No breathless headlines. No "everything is changing" filler. Just who moved, what broke, and why it matters.

Free. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

This is the pattern that keeps emerging in agentic AI work. Engineers build elaborate scaffolding, then discover that a capable model with good tools outperforms the scaffolding. Sophisticated architectures break. Simple ones ship.

The mechanics of a trail

One hundred books, scraped from Hacker News favorites, sit in a SQLite database. Gemini 2.5 Flash Lite extracted topics from each 500-word chunk, a process that cost roughly ten pounds for the entire corpus. Topics get embedded, clustered, merged when their labels overlap. The structure that emerges isn't a filing cabinet. It's terrain. Dense concept clusters rise into peaks; isolated themes sink into valleys. Maes ended up with 100,000 topics. After clustering, about 1,000 remained browsable.

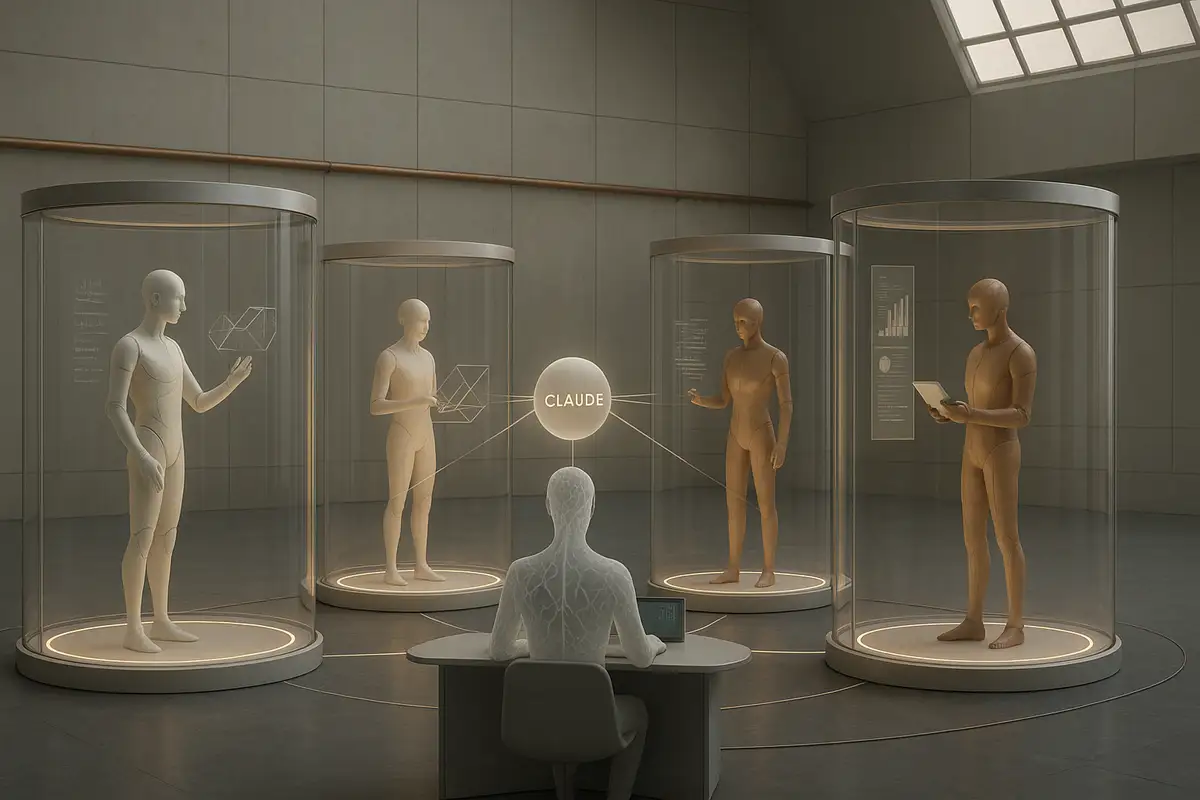

Claude works through this structure using CLI tools. It runs a search, gets a list of chunks tagged with related topics, adjusts the query, runs it again. You can watch the agent backtrack. The tools don't summarize. They point.

Trail generation happens in three stages. First, Claude scans the library and proposes ideas, mostly browsing the topic tree without reading deeply. Second, it takes an idea and builds the trail, reading chunks, extracting specific sentences, deciding how to order them. Third, it highlights key phrases and draws connections between consecutive excerpts.

The technical implementation is clever but unremarkable. What's interesting is what Maes learned by watching it work.

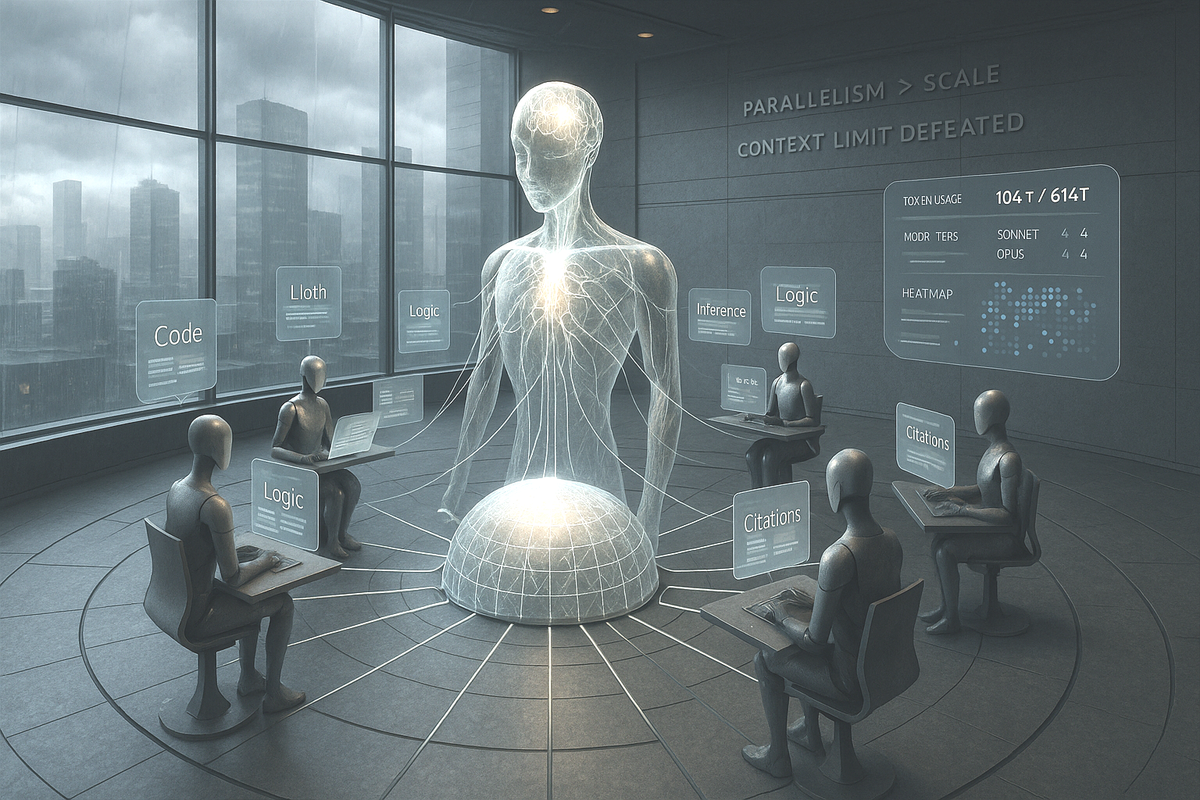

The coworker model

His mental model shifted. "From a function mapping input to output, to a coworker I was assisting."

This sounds soft, but it changed what he built. Instead of optimizing prompts, he started implementing better tools. Instead of guessing what Claude needed, he asked. Claude proposed new commands, Claude implemented them, Claude used them to do better work.

Maes ended up using Claude as his primary interface to the project. Not just for finding trails. For everything. The agent recalled CLI sequences faster than he could. It automated tasks too irregular for traditional scripts. When Maes changed his mind about how long excerpts should be, Claude revised all existing trails, balancing each edit against how the overall meaning shifted.

"Previously, I would've likely considered all previous trails to be outdated and generated new ones, because the required edits would've been too messy to specify."

This is the part that matters for how AI tools will be used. Not summarization. Not generation. Cheap revision. When changing your mind costs almost nothing, you make better decisions. You don't lock into early choices because unwinding them would be too expensive. Momentum shifts from the first idea to the best idea. Tool builders should feel nervous. So should anyone whose job involves maintaining the scaffolding between human intent and machine execution.

The novelty heuristic

How do you optimize for "interesting"? You don't. You can't quantify it. But you can quantify novelty.

Maes implemented this two ways. Algorithmically, he biased search results toward under-explored topics, measured by embedding distance from nearest neighbors. In the prompt, he showed Claude the existing trails and asked it to avoid conceptual overlap.

Both worked. The algorithm surfaced material that hadn't been connected yet. The prompt kept Claude from repeating itself.

Get Implicator.ai in your inbox

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

But the prompt revealed something else. Claude kept drifting toward certain themes. Secrecy. Systems theory. Tacit knowledge. Conspiracy.

Maes put it well: "It's as if the very act of finding connections in a corpus summons the spirit of Umberto Eco."

Foucault's Pendulum is the reference here. Eco's characters spend hundreds of pages feeding historical trivia into a computer, producing an increasingly baroque conspiracy theory that eventually consumes them. They don't discover anything. They invent it. And the invention feels true because the machine keeps finding reasons to connect things. That's the risk with any system optimized to find links. It will find links. Whether those links exist outside the model is a separate question.

Maes noticed this as a tendency, not a failure. Claude found real connections. It also found them more readily when the topics were themselves about hidden connections. The bias is worth naming because it probably exists in other agentic systems doing similar work.

What this means for reading

The Hacker News discussion surfaced a useful distinction. One commenter pointed to "distant reading," a digital humanities technique that zooms out to thousands of texts, using computation to surface patterns invisible at close range. The opposite of close reading, where you focus intensely on a single passage.

Maes's system sits between them. It's not close reading. Claude isn't interpreting a sentence in context. It's not quite distant reading either. The output isn't statistical. It's narrative. A sequence of excerpts that build an argument.

Call it syntopic reading with a librarian in the loop. The AI expands the search space. Human judgment prunes it. Each cycle sharpens understanding.

What's missing, for now, is verification. The phrase-to-phrase links Claude draws between excerpts don't always hold. In one trail, Claude connected "fictions" to "internal motives," a link that makes sense if you squint but wouldn't survive a seminar. The system finds words that rhyme thematically, then presents the rhyme as reasoning. The trail from Jobs to Hoffer feels solid. Other trails feel more like juxtaposition dressed up as argument.

The reader still has to do the work of deciding whether the connection is real. But that's always been true of reading across sources. The difference is surface area. One person with good tools can now browse a hundred books looking for thematic overlaps. The labor moved from "find the passages" to "evaluate the claim."

Nobody has a good word for this yet. Syntopic reading comes closest, but it's clunky. Whatever you call it, this is new territory. And the librarian is in the loop.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How much did it cost to process 100 books?

A: About £10. Maes used Gemini 2.5 Flash Lite for topic extraction, processing roughly 60 million input tokens across the entire corpus. The books were chunked into 500-word segments, with 3-5 topics extracted per chunk.

Q: Why did the hand-tuned pipeline fail?

A: It returned what Maes baked into the prompts. If he mentioned "leadership," it surfaced leadership passages. The connections were accurate but unsurprising. The agent, given tools and freedom to wander, made connections the pipeline missed.

Q: What is syntopic reading?

A: Reading across multiple books on related subjects to find how different authors approach the same questions. Mortimer Adler coined the term. Maes automated the search phase, letting Claude surface candidate passages while humans evaluate whether the connections hold.

Q: What's the "Umberto Eco problem" with this approach?

A: Systems optimized to find links will find links. In Eco's novel *Foucault's Pendulum*, characters feed trivia into a computer and generate an elaborate conspiracy theory. Claude showed similar drift toward secrecy and conspiracy themes. Some connections are real; others just feel real.

Q: Can I try this system myself?

A: Maes published the results at trails.pieterma.es, where you can browse the trails Claude generated. The underlying code isn't open-sourced, but the blog post at pieterma.es/syntopic-reading-claude details the architecture: SQLite storage, Gemini for extraction, Claude Code for trail generation.