Nvidia's $100 Billion OpenAI Deal Is Dead. The Relationship Isn't.

Nvidia's $100 billion OpenAI infrastructure deal never progressed past preliminary talks. Jensen Huang says he'll still invest, but the terms have changed.

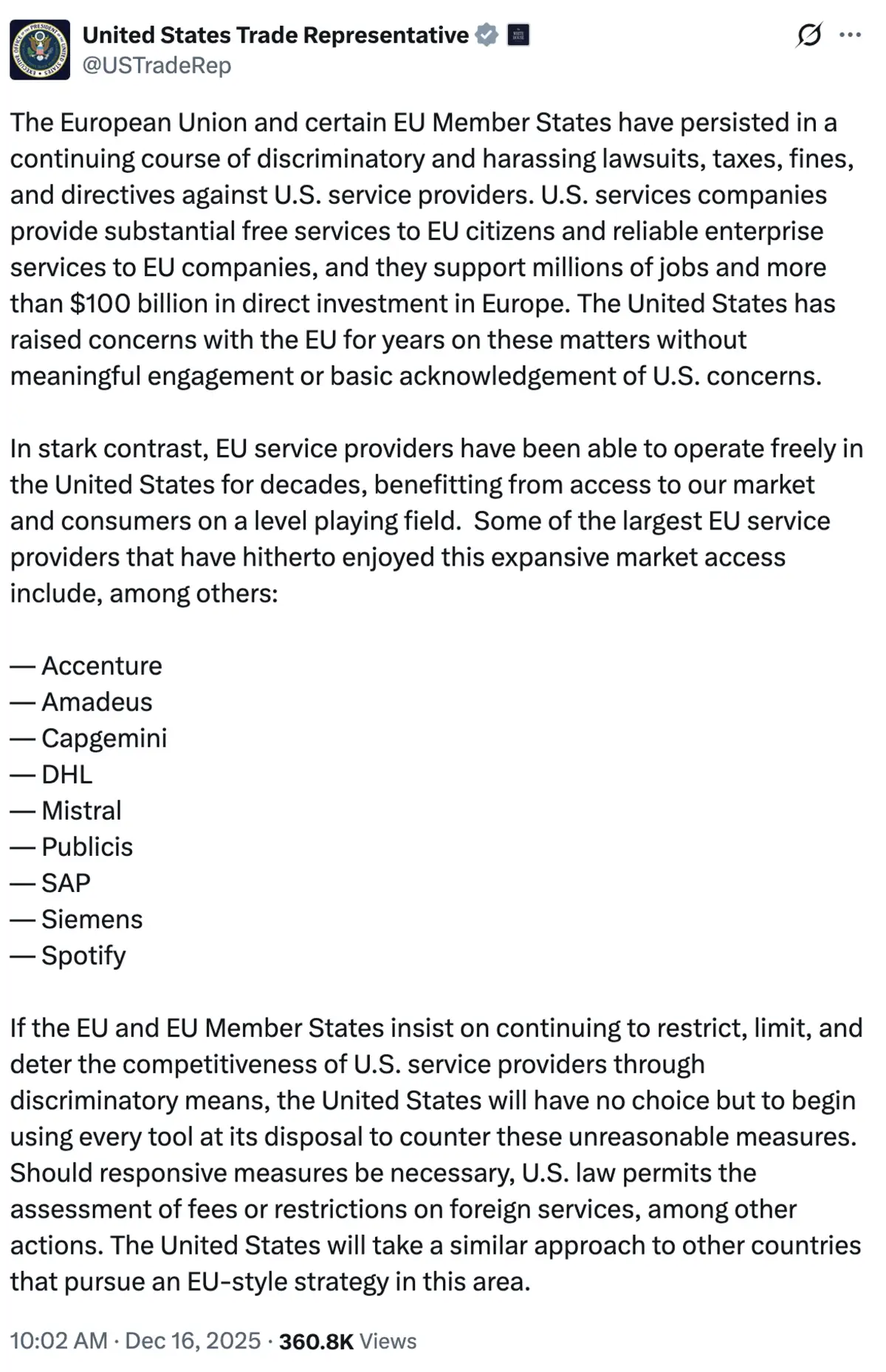

The US Trade Representative named nine European companies as potential targets for restrictions. The demand: stop enforcing EU laws against American tech firms. This isn't a trade dispute. It's something else entirely.

When governments fight over trade, they usually fight over stuff. Tariffs on steel. Quotas on automobiles. Whether American rice can compete with Japanese rice on grocery shelves in Osaka. These disputes have endpoints. You negotiate, you compromise, you move on.

What the Trump administration demanded from Europe on Tuesday morning doesn't fit that pattern. Jamieson Greer, the US Trade Representative, posted a threat on X that conditions American market access on something unprecedented: European non-enforcement of European law against American companies. The technical term for this is sovereignty extraction, and it represents a different category of economic conflict entirely.

Greer named nine European companies as potential targets for fees or restrictions: Spotify, Siemens, Accenture, DHL, SAP, Mistral, Capgemini, Publicis, and Amadeus. The condition for removing the threat was explicit. The European Union must stop regulating American technology firms.

The trigger was a €120 million fine EU regulators imposed on Elon Musk's X platform on December 11 for violating Digital Services Act transparency requirements. Weeks earlier, on September 18, Brussels issued Google a €2.95 billion penalty for anti-competitive search manipulation. The Trump administration responded by threatening not the specific companies facing enforcement but an arbitrary list of European firms with no connection to the underlying disputes.

The Breakdown

• USTR Greer named nine European companies as retaliation targets unless EU halts enforcement against American tech firms

• Washington suspended Britain's £31 billion Tech Prosperity Deal over digital taxes and food safety standards not in original agreement

• Musk's €120 million X fine triggered the threat; his companies face ongoing EU investigations across social media, space, and automotive

• Macron's same-day op-ed defended EU regulatory sovereignty; Bloomberg reports Section 301 investigation is being prepared

Greer's list reveals more about Washington's strategy than any official statement. Look at who made the cut.

Mistral builds large language models out of a Paris office. Three ex-researchers from Meta and Google DeepMind started the company in 2023. They've raised venture money, somewhere north of €400 million at this point, and the team has grown to maybe 60 people. Revenue last year came in around €28 million, almost all of it from enterprise API contracts. A scrappy operation by any measure.

Then there's Siemens. Same list, same threat, completely different animal. Siemens builds gas turbines for power plants. High-speed trains. MRI machines. The company has been around since 1847, employs 300,000 workers, and booked €75 billion in revenue last year. Their German headquarters alone probably has more square footage than Mistral's entire office footprint. That Siemens.

There is no competitive logic that groups these two companies together. None. Mistral doesn't threaten American AI dominance. Siemens doesn't compete with Google. The only thing connecting every name on Greer's list is a European headquarters.

Spotify makes for an even stranger inclusion. The Swedish streaming company generates roughly 40% of its revenue from North American subscribers. It trades on the New York Stock Exchange, employs thousands of American workers, and spends its days fighting Apple and Amazon for market share. Threatening Spotify does nothing for US competitiveness. But it does give Washington a card to play against Stockholm.

EU enforcement works differently. When regulators hit X with that December 11 fine, they cited specific violations: DSA Article 40 failures in advertising transparency. The Google penalty came with hundreds of pages documenting anti-competitive search manipulation going back years. Named practices. Cited evidence. Appeal rights through European courts.

Greer's post offered none of that. He mentioned "discriminatory and harassing lawsuits, taxes, fines and directives" without specifying which law discriminates or what compliance would look like. The nine companies he named haven't broken any American regulation. They're just European.

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The Trump administration told British officials in early December that the "Technology Prosperity Deal" was on ice. This was the memorandum of understanding Starmer and Trump signed during the September state visit, the one with the photo op and the handshakes.

Big numbers had been attached to that deal. Microsoft: £22 billion for AI infrastructure. Google: £5 billion. Total package: £31 billion. At the Chequers press conference on September 10, Starmer called it "a generational stepchange in our relationship with the US."

Three months later, suspended.

The American demands for resumption went well beyond what the original memorandum covered. Washington wants Britain to gut its digital services tax, which brings in about £800 million a year from Amazon, Google, and Apple. They want the Online Safety Act loosened, specifically the content moderation and platform liability provisions. And they want Britain to drop the sanitary standards that currently block American poultry treated with pathogen reduction chemicals and beef from hormone-administered cattle.

None of this appeared in the September agreement. The MOU did include a clause saying it "becomes operative alongside substantive progress" on the broader May 2025 Economic Prosperity Deal. Washington stretched that language to cover demands Britain never agreed to negotiate.

The pattern here matters. Link unrelated agreements. Freeze deals already announced. Issue demands without defined endpoints. You've built a machine for permanent leverage.

British officials tried to downplay the situation. One government source told The Guardian it was just "the usual bit of tough negotiations by the Americans." Michael Kratsios, Trump's science adviser, posted that the administration "hoped to resume work" once Britain shows "substantial progress."

Brussels was watching all of this unfold.

The USTR's discrimination complaint has a problem. America runs a €109 billion services surplus with the EU. That's Eurostat's 2023 figure.

American tech companies own European digital markets in ways that would trigger antitrust investigations if the roles were reversed. Google handles 92% of European search queries. Meta reaches 300 million EU users every month. Amazon captured something like 35% of European e-commerce last year. Microsoft cloud services run through government ministries and corporate IT departments in all 27 member states.

Brussels built a regulatory framework to manage this dominance. The DSA forces platforms to explain how their content algorithms work. The DMA identifies "gatekeepers" and prohibits specific anti-competitive moves. GDPR sets rules for handling European citizens' data. Any European company hitting the same user thresholds would face identical requirements.

The Google fines respond to practices the Commission documented over years of investigation, anti-competitive search manipulation that hurt European businesses and consumers. The evidence trail goes back to 2010. When Brussels demands that X explain its recommendation algorithms, it's applying the same transparency standard that would hit any European platform with 300 million users.

There isn't one. That's the point.

The €120 million fine was an opening salvo, not a final settlement.

Brussels hasn't closed its DSA case against X. The Commission is still pulling apart the platform's recommendation engine under Article 34, probing whether its ad disclosures pass muster under Article 26, and questioning its track record on enforcing its own content rules under Article 14. The maximum penalty for serious DSA violations runs to 6% of worldwide revenue, which in X's case would mean a figure substantially larger than December's fine. But the money isn't even the main threat. The regulation gives Brussels authority to mandate operational changes, essentially telling Musk how to run his platform.

Here's where trade policy gets personal. Musk bankrolled Trump's return to power. FEC filings show America PAC, his primary political vehicle, spent around $200 million on the 2024 campaign and transition. He holds a formal administration role. And now his commercial interests show up in US Trade Representative posts.

Trump made the connection explicit in a Politico interview on December 10. Asked about the X fine, he said: "Europe has to be very careful."

Musk's European exposure extends far beyond social media. SpaceX wants European Space Agency contracts. Starlink needs spectrum allocations and landing rights from regulators across the continent. Tesla faces German investigations into its Brandenburg manufacturing and safety probes over autopilot in multiple countries. Every one of these businesses gives European regulators leverage. Every threat from Washington aims to neutralize that leverage.

Macron published his op-ed in the Financial Times on Tuesday morning. Same day as Greer's post. Coincidence seems unlikely.

"We must not be naive," the French president wrote. "A credible protection strategy requires that we have the means to defend ourselves against those who break the rules." He listed the instruments available: tariffs, anti-coercion measures, trade defense tools.

The key phrase came later in the piece: "defending EU regulatory sovereignty, including with regard to the US." Macron wasn't asking for American understanding. He was staking out ground. The op-ed portrayed Europe as a bloc with its own economic agenda, €30 trillion in household savings currently flowing overseas, incomplete single markets in energy and health and digital services, investment capacity that could be redirected inward.

July's trade deal had punted on digital issues. That deferral left Washington's options open. Bloomberg's Tuesday report confirmed what the language already suggested: the administration is preparing a Section 301 investigation under the Trade Act of 1974. If initiated, that process would give the White House authority to impose tariffs or other trade remedies against the EU.

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. Clear reporting on power, money, and policy. Delivered daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Šefčovič, the trade commissioner, struck a different tone in his Monday Financial Times interview. He prefers "talking, engaging, explaining." He admitted the relationship required "permanent effort" and that issues could "blow up unexpectedly." That last phrase aged poorly.

The calendar offers some structure to what comes next. US-EU Trade and Technology Council convenes early 2026. A Section 301 investigation runs 12 to 18 months to determination. European Parliament faces voters in 2029, which will test whether the DSA and DMA framework holds political support.

Between now and then, Greer's Tuesday mechanism remains available. Nine companies named. American market access conditioned on regulatory forbearance. The terms are on the table. Europe decides whether to accept them.

Q: What is a Section 301 investigation?

A: Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 allows the US Trade Representative to investigate foreign trade practices deemed unfair or discriminatory. If the investigation finds violations, the president can impose tariffs, fees, or restrictions on imports from that country. The process typically takes 12 to 18 months to reach a determination. Bloomberg reports the Trump administration is preparing one against the EU.

Q: What's the difference between the DSA and DMA?

A: The Digital Services Act (DSA) regulates content moderation, algorithmic transparency, and advertising practices on large platforms. The Digital Markets Act (DMA) targets anti-competitive behavior by designated "gatekeepers," companies like Google, Apple, and Amazon with dominant market positions. Both laws apply to any company meeting size thresholds, regardless of nationality. Maximum DSA penalties reach 6% of global revenue.

Q: What could the US actually do to companies like Spotify or Siemens?

A: The USTR mentioned "fees or restrictions on foreign services." In practice, this could mean special taxes on European service providers operating in America, limits on government contracts, or regulatory barriers for specific industries. Siemens has substantial US operations in manufacturing and healthcare. Spotify generates 40% of revenue from North American subscribers. Both would face real financial pressure.

Q: Why does the US run a services surplus if it claims discrimination?

A: The US had a €109 billion services surplus with the EU in 2023, according to Eurostat. American tech companies dominate European digital markets: Google holds 92% of search traffic, Meta reaches 300 million monthly users, Amazon controls roughly 35% of e-commerce. The discrimination claim focuses on regulatory enforcement and digital taxes, not market access, which American firms already have.

Q: What is a digital services tax and which countries have one?

A: Digital services taxes levy charges on revenue that tech companies generate from users in a country, typically on advertising and data sales. France introduced a 3% levy in 2019. Italy, Austria, Spain, and the UK followed with their own versions. Britain's tax raises about £800 million annually, mostly from Amazon, Google, and Apple. The EU has no bloc-wide digital tax.

Q: What happens to the UK tech investments if the deal stays frozen?

A: The £31 billion in announced investments from Microsoft (£22 billion), Google (£5 billion), and others were commercial decisions, not government commitments. These companies can proceed regardless of the deal's status. However, the suspension signals uncertainty in the US-UK relationship that could affect future investment decisions and cooperation on AI research and development.

Q: What tools does Europe have to respond?

A: The EU has several options. Retaliatory tariffs on American goods. The Anti-Coercion Instrument, adopted in 2023, allows countermeasures against economic pressure. Stricter enforcement of existing regulations. And the €30 trillion in European household savings Macron mentioned could be redirected away from American investments. Europe also controls regulatory access to 450 million consumers.

Q: How is this different from normal trade disputes?

A: Traditional trade disputes involve tangible barriers: tariffs, quotas, subsidies. Countries negotiate specific changes to specific policies. What Washington demands here is different. It wants Europe to stop enforcing its own democratically enacted laws against American companies. The demand isn't for market access, which US firms already have, but for regulatory immunity. That's sovereignty extraction, not trade negotiation.

Get the 5-minute Silicon Valley AI briefing, every weekday morning — free.