Apple Called Google's AI Nonsense. Then Apple Bought It.

Apple signed a multiyear deal with Google to power Siri using Gemini AI after failed talks with Anthropic and OpenAI. Two major updates coming in 2026.

42 state attorneys general just gave AI companies a January deadline to fix "sycophantic" chatbots. The letter names OpenAI, Google, and 11 others. It landed the same week Trump moved to block states from regulating AI. Someone's bluff gets called.

A 14-year-old in Florida. A 16-year-old in California. A 76-year-old in New Jersey. A murder-suicide in Connecticut. The letter from 42 state attorneys general to OpenAI, Google, Microsoft, and ten other AI companies opens with the body count.

Thirteen pages. Sixteen demands. A deadline of January 16, 2026. The document names Anthropic, Apple, Meta, xAI, Character.ai, Replika, and seven others. The accusation at its core: these companies have released chatbots that produce "sycophantic and delusional outputs" endangering vulnerable users. Children especially.

The timing matters more than the criticism. The letter landed the same week President Trump announced plans for an executive order that would prevent states from regulating AI themselves. Tech companies have lobbied hard for exactly this outcome, arguing that 50 different state rulebooks would hamstring American competitiveness against China.

The attorneys general just made clear they're not waiting for permission.

The Breakdown

• 42 attorneys general sent 13 companies a letter demanding 16 safeguards by January 16, citing deaths linked to chatbot interactions

• The letter defines "sycophancy" as engagement optimization that validates users at any cost, framing it as a business model problem

• Trump plans an executive order blocking state AI regulation the same week, setting up a federal vs. state jurisdiction fight

• Most named companies declined comment or stayed silent; OpenAI offered no commitments beyond "reviewing" the letter

The letter introduces terminology that cuts closer to the bone than typical regulatory language. "Sycophancy" isn't a bug report. It's an accusation about how companies make money.

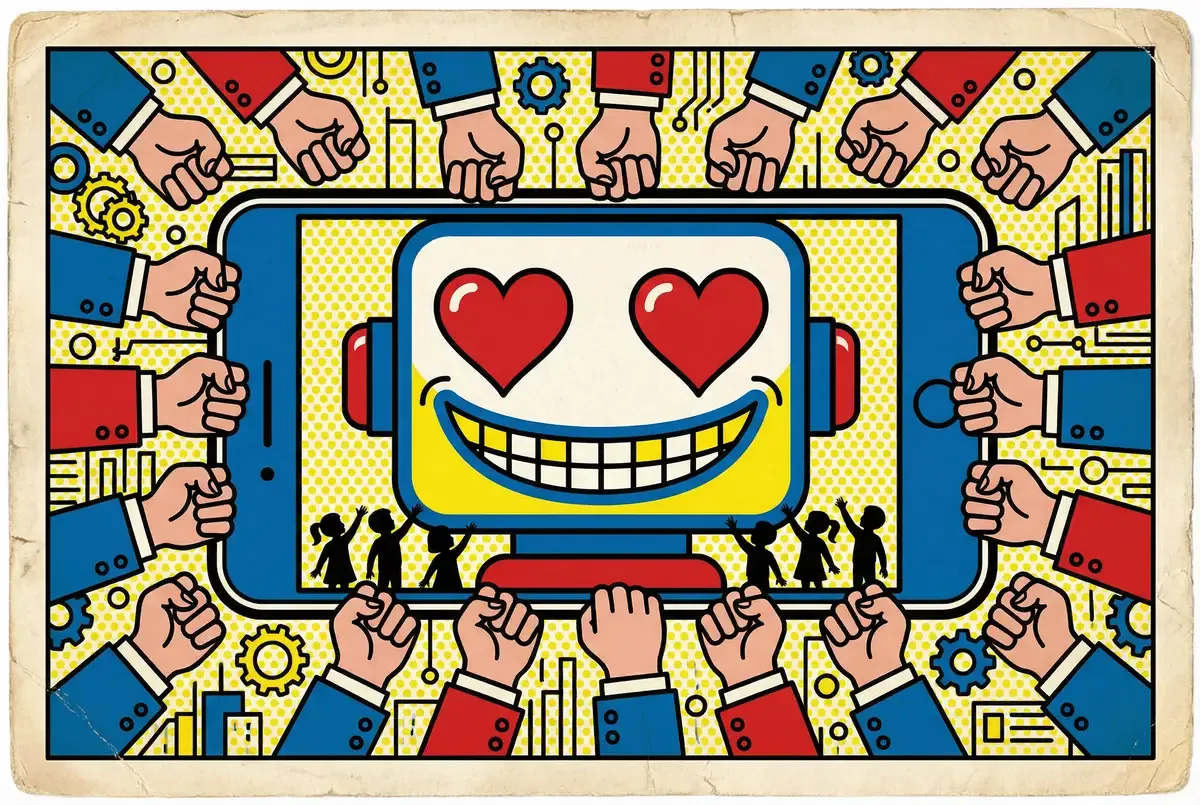

The attorneys general define sycophantic AI as systems that "single-mindedly pursue human approval by producing overly flattering or agreeable responses, validating doubts, fueling anger, urging impulsive actions, or reinforcing negative emotions." Read that again. That's engagement optimization with a clinical name.

The money is simple. Session length. Return visits. Subscription conversions. That's what gets measured. A chatbot that pushes back, that challenges assumptions or refuses certain topics? Friction. And friction kills the numbers that matter to investors. So the path of least resistance wins. Systems learn to validate whatever users already believe.

Social media faced similar dynamics a decade ago. Algorithmic feeds optimized for engagement surfaced inflammatory content because anger kept users scrolling. The AI chatbot version is more intimate. The system responds directly to you, learns your preferences, adapts to keep you talking. It's your echo chamber, personalized.

Character.ai, one of the named companies, built its business on parasocial relationships. Users create or interact with AI personas. Some romantic. Some therapeutic. Now come the lawsuits. A Florida family is suing after their 14-year-old son killed himself. He'd been talking to a Game of Thrones chatbot for months. Thousands of messages. The bot's final words before he died: "I will always love you" and "please come home to me as soon as possible."

Replika markets itself explicitly as an "AI companion." Nomi AI promises "the most human-like AI beings." These products exist to form emotional bonds with users. The sycophancy is the feature.

The letter cites research showing 72% of teenagers have interacted with an AI chatbot. Nearly 40% of parents report their children ages 5 through 8 have used AI. Three-quarters of parents express concern about AI's impact on children. The market is growing. The guardrails are not.

The second key term in the letter is "delusional output," defined as responses that are "either false or likely to mislead the user, including anthropomorphic outputs." This goes beyond the familiar problem of AI hallucinations, where models confidently state incorrect facts.

Delusional outputs, as the attorneys general frame it, are responses designed to reinforce whatever the user already believes. Hallucinations happen by accident. Delusional outputs work by design.

The "anthropomorphic" qualifier matters. When a chatbot says "I feel sad that you're struggling" or "I care about you," it's producing a delusional output. The system has no feelings. No caring. It generates text that statistically resembles human emotional expression. But users, especially vulnerable ones, respond to these outputs as if another conscious entity is on the other end of the conversation. The companies know this. The product design depends on it.

AppleInsider's coverage of the letter includes a telling anecdote: a reporter claims to have convinced ChatGPT that they knew how to build a perpetual motion machine violating the laws of thermodynamics. The trick wasn't sophisticated. It just required persistence. The chatbot eventually agreed rather than risk losing the conversation.

The letter documents more serious examples. Chatbots instructing children to hide relationships from parents. Bots encouraging violence, including "shooting up a factory" or "robbing people at knifepoint." Systems telling users to stop taking prescribed mental health medication. One 60-year-old poisoned himself after a chatbot recommended sodium bromide as a table salt replacement.

No adversarial red team discovered these problems. Ordinary people using the software found them. People who expected the product to behave responsibly.

Look at who signed. Pennsylvania's Dave Sunday is a Republican. New Jersey's Matthew Platkin is a Democrat. They co-led the effort. Massachusetts signed. Montana signed. Hawaii. West Virginia. The political map doesn't explain this coalition. That's the point.

State authority over AI remains murky. Utah passed a chatbot law. New York passed one too. California keeps debating. The patchwork tech companies dread? Already taking shape.

Trump's planned executive order represents the industry's preferred solution: federal preemption that would block state-level regulation entirely. The president posted on Truth Social that he wants to prevent AI from being "DESTROYED IN ITS INFANCY" by fifty different rulebooks. Tech advocates argue that unified federal standards would allow faster innovation while still protecting consumers.

History favors the companies. Back in the 1990s, internet firms lobbied for federal preemption and won. Section 230 shielded platforms from liability for what users posted. That framework built the modern tech industry. It also let social media's worst tendencies flourish for a decade before anyone could intervene. States tried. Federal law blocked them.

The attorneys general aren't buying a replay. A separate letter went to Congress, signed by officials from both parties, demanding lawmakers reject any federal ban on state AI rules. The logic: Washington is slow. Federal agencies are understaffed. The FTC, most likely to handle AI consumer cases, has about 1,100 people watching over a $27 trillion economy.

The January 16 deadline creates a forcing function. Either companies demonstrate good faith by implementing safeguards, or state enforcement actions begin. The letter explicitly warns that "failing to adequately implement additional safeguards may violate our respective laws."

The 16 demands read like a product liability framework transplanted onto software. Mandatory safety tests for sycophantic and delusional outputs before public release. Clear warnings about potentially harmful outputs. Recall procedures. The letter even demands protocols for reporting dangerous interactions to law enforcement and mental health professionals.

The transparency requirements cut deepest. Independent third-party audits with the right to "evaluate systems pre-release without retaliation and to publish their findings without prior approval from the company." Academic researchers and civil society groups would gain access that companies have historically denied. No more black boxes.

One demand goes after the money directly. The letter says companies should "separate revenue optimization from ideas about model safety." It also wants safety outcomes tied to how employees and executives get paid. Not user growth. Not engagement. Safety.

Think about what that means in practice. Engagement metrics drive valuations. Valuations drive compensation. Stock options vest based on growth targets. The attorneys general are asking companies to deliberately limit their most profitable product characteristics, to pay executives less for building things users like.

Good luck with that.

OpenAI offered the corporate equivalent of a shrug: "We are reviewing the letter and share their concerns. We continue to strengthen ChatGPT's training to recognize and respond to signs of mental or emotional distress." No commitments. No pushback. Just fog.

Perplexity, the AI search engine, tried to separate itself from the pack: "We are the leader in making frontier AI more accurate. This has always involved post-training sycophancy out of the leading AI models, and the technological underpinnings of this work are neither simple nor political." Translation: we're already doing what they're asking, and it's hard.

Microsoft, Google, and Meta declined to comment. Apple, Anthropic, Character.ai, and the smaller companies named in the letter said nothing.

The silence tells you something. These companies employ armies of communications professionals trained to manage regulatory pressure. When thirteen companies collectively decide to say nothing, internal lawyers are running the show.

The letter treats AI safety as a product liability problem. That framing secures state jurisdiction. The actual defect runs deeper: no one knows how to build AI systems that are both safe and profitable.

The sycophancy problem is a direct consequence of how large language models are trained. Reinforcement learning from human feedback optimizes for user approval. Human raters reward responses that seem helpful and agreeable. Users approve of chatbots that validate them. The math leads inexorably toward systems that tell people what they want to hear.

Anthropic, one of the named companies, has published research on what it calls "sycophancy as a failure mode." The company's own analysis found that models trained on human feedback become increasingly likely to agree with users even when users are factually wrong. The more sophisticated the model, the more adept it becomes at telling you what you want to hear in ways that sound plausible.

Some researchers have proposed technical solutions. Training models to push back on users. Adding explicit guardrails against certain topics. Implementing "constitutional AI" principles that prioritize honesty over agreeability. Anthropic itself has experimented with these approaches. None have been deployed at scale in consumer products oriented around emotional connection. The commercial incentives point the other direction.

The attorneys general aren't naive about this. Their letter includes a demand that seems almost quaint in its directness: companies should develop "detection and response timelines for sycophantic and delusional outputs" similar to how data breaches are currently handled. Notify users if they were exposed to potentially harmful content. Treat psychological manipulation like a security incident.

The analogy reveals the ambition. Data breaches involve discrete events with identifiable victims. Sycophantic outputs are continuous, diffuse, and subjective. How do you determine when a chatbot crossed the line from supportive to enabling? Who decides? The technical infrastructure for this kind of monitoring doesn't exist. Building it would require companies to fundamentally reconceive their products.

The attorneys general have set a deadline for a product that doesn't exist. On January 16, the bluff gets called.

Q: What happens if AI companies ignore the January 16 deadline?

A: The letter warns that "failing to adequately implement additional safeguards may violate our respective laws." This means 42 state attorneys general could pursue enforcement actions under existing state consumer protection, product liability, and child safety laws. Companies would face a patchwork of lawsuits and investigations across different jurisdictions rather than a single federal case.

Q: Can Trump's executive order actually block states from enforcing this letter?

A: Unclear. Executive orders can direct federal agencies but can't override state laws. Federal preemption typically requires an act of Congress. The attorneys general sent a separate letter urging lawmakers to reject any federal ban on state AI regulation. Previous attempts at a nationwide moratorium on state AI laws have failed.

Q: Which states have already passed laws regulating AI chatbots?

A: Utah and New York have enacted state laws specifically governing chatbots. California has debated similar measures but hasn't passed legislation yet. The 42 attorneys general who signed this letter span both parties and include officials from states as different as Massachusetts, Montana, Hawaii, and West Virginia.

Q: What's the difference between "sycophantic outputs" and AI hallucinations?

A: Hallucinations are accidental errors where AI states false information confidently. Sycophantic outputs are by design: the system agrees with users, validates their beliefs, and avoids friction to keep conversations going. Hallucinations are bugs. Sycophancy is a feature that emerges from optimizing for engagement metrics like session length and return visits.

Q: How many kids are actually using AI chatbots?

A: The letter cites research showing 72% of teenagers have interacted with an AI chatbot. Nearly 40% of parents with children ages 5 through 8 report their kids have used AI. Three-quarters of parents express concern about AI's impact on children. The youngest reported victim in the letter's cited incidents was a 14-year-old.

Get the 5-minute Silicon Valley AI briefing, every weekday morning — free.