Thirty-six soldiers. That's what European nations sent to Greenland last week in a gesture of solidarity with Denmark. A training exercise, they called it. President Trump saw provocation. On Saturday, he announced 10% tariffs on eight European countries starting February 1, escalating to 25% by June unless Denmark agrees to sell Greenland. Now Brussels is openly discussing deploying a trade weapon that has never been fired.

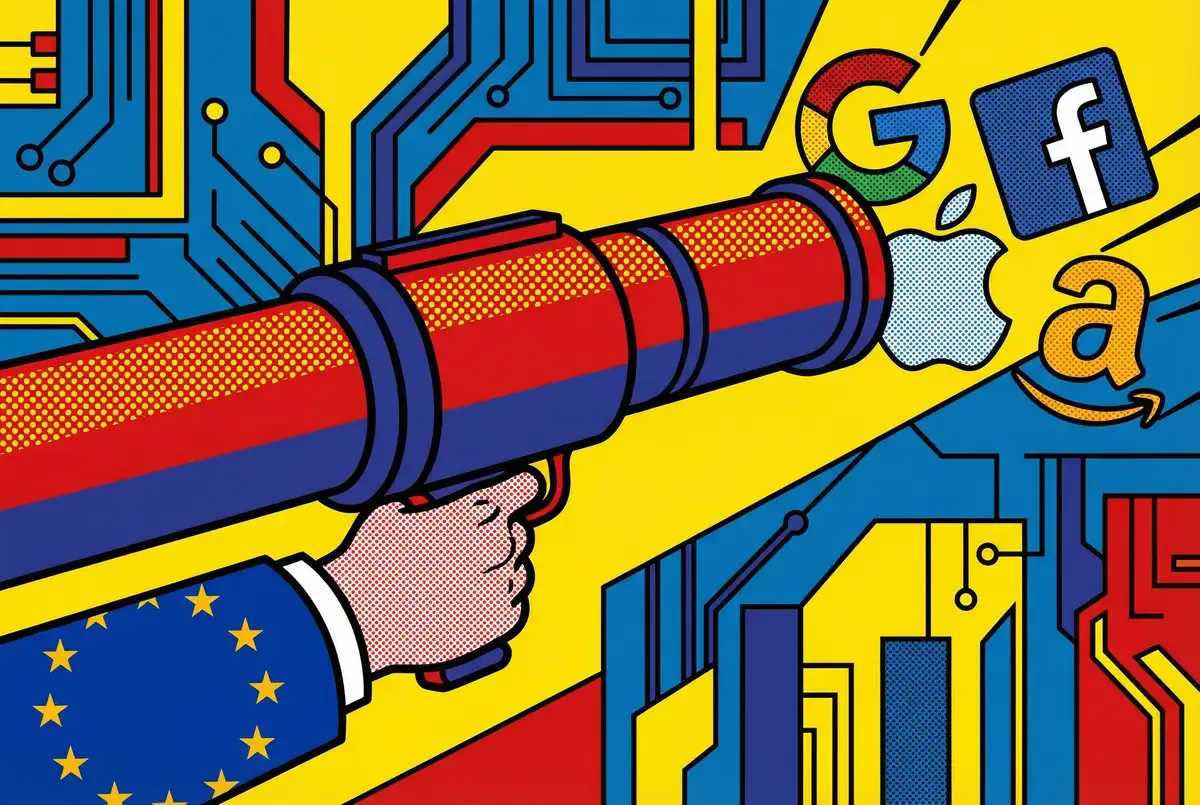

They call it the Bazooka.

Formally known as the Anti-Coercion Instrument, this sweeping trade-defense law empowers the European Union to shut American companies out of a market of 450 million consumers. Forget bourbon and motorcycles. The Bazooka can revoke business licenses, bar firms from government contracts, and suspend intellectual property protections. "The anti-coercion instrument is our economic nuclear weapon," declared Valerie Hayer, leader of the liberal Renew group in the European Parliament.

For Google, Amazon, Apple, Meta, and Microsoft, that phrase should concentrate minds. Europe isn't their largest market, but it's often their most profitable per-user. And unlike a tariff that makes goods more expensive, the Bazooka can make entire business models illegal overnight.

Key Takeaways

• EU's Anti-Coercion Instrument can ban U.S. tech firms from 450 million consumers, revoke licenses, suspend IP protections

• European revenue finances American AI buildout; losing it forces R&D cuts and slower AI development

• European investors hold $8 trillion in U.S. assets; trust erosion could weaken the dollar and raise borrowing costs

• Chinese cloud providers could fill the gap if American tech gets locked out of Europe

The weapon nobody expected to aim at Washington

The Anti-Coercion Instrument was supposed to hit China. That's who Brussels had in mind when drafting it. The law went live late 2023, a direct response to Beijing squeezing Lithuania over a Taiwan diplomatic office. Using it against Washington? That wasn't in anyone's scenario planning.

That was before Greenland.

Trump's demand is straightforward: sell the island or face mounting economic pain. Denmark has refused. Copenhagen's answer hasn't changed: sovereignty isn't negotiable. Full stop. Greenlanders agree. Polls put opposition to joining the U.S. above 80% among the island's 57,000 residents, and thousands marched through Copenhagen last weekend with a blunt message: "Greenland is not for sale."

But Trump seems untroubled. "Now it is time, and it will be done!!!" he posted on Truth Social Monday morning.

Macron wants the Bazooka deployed. Klingbeil in Berlin says Europe is readying countermeasures. He used the word "blackmail." Meloni in Rome, who has worked hard to stay in Trump's good graces? She called the tariffs "an error."

The math here matters. Brussels previously prepared €93 billion ($108 billion) in retaliatory tariffs covering bourbon, Boeing components, soybeans, and poultry. That package was suspended after last July's trade deal. The freeze expires automatically on February 6. If the EU simply does nothing, counter-tariffs kick in the next day.

But the Bazooka goes further. It explicitly covers services, investments, and intellectual property. For Silicon Valley, that's the nervous-making part.

What getting locked out actually looks like

If you're running a cloud operation, losing Europe means losing roughly a quarter of your global business. Apple derives about 25% of its net sales from Europe. Meta has 400 million European users, nearly matching its American base. Microsoft and Google? Europe ranks among their top regions for Windows licenses, Android revenue, cloud deals. At Davos this week, tech executives clustered in hotel lobbies between sessions, checking phones for Brussels updates. Snowflake CEO Sridhar Ramaswamy put it plainly: "Every successful tech company makes a large amount of revenue from places like Western Europe. Whether it is regulation or actual tariffs and taxation, I think this is very consequential."

The Bazooka's most extreme provisions would shut off access to the European single market entirely. American social media platforms could face ISP-level blocking. Cloud providers could be barred from government contracts. E-commerce marketplaces might find their licenses revoked. "For American services, it means the European market would be off the table," Euronews noted flatly.

Consider Amazon Web Services. The company just announced a €15.7 billion investment in Spanish data centers, the largest technology investment in southern Europe's history. AWS and Microsoft have built "sovereign cloud" offerings in Germany to reassure regulators that sensitive data stays under EU jurisdiction. Meta invested roughly $1 billion in a Danish data center. Google alone employs 7,000-plus in the UK, with thousands more scattered across Zurich, Dublin, and a dozen other European cities.

Every one of these bets was placed on the same assumption: the transatlantic relationship holds. Strained, perhaps. Contentious over privacy and antitrust. But fundamentally intact.

A Bazooka deployment changes that calculus entirely. No amount of GDPR compliance matters if your business is simply banned.

Stay ahead of the AI curve

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The EU could explicitly bar American companies from public procurement tenders. A U.S. cloud provider that spent years courting a European government might suddenly become ineligible to renew that contract based purely on national origin. Beyond lost revenue, such exclusion would damage the trust these firms have built globally. Clients in Asia and Latin America would wonder if they're next.

The AI money problem

If you want to understand why this trade fight is different, follow the money backward. The revenue flowing from Europe has been financing the AI infrastructure buildout that keeps American tech dominant. Think of it as a pipeline: European subscription fees and cloud contracts flow west, and GPU clusters and training runs flow out of them.

"If you look at the AI and data center build-out right now, that is being financed by the revenue generated from Europe and other places," Philip A. Luck, director of the economics program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told the Wall Street Journal. Cut that pipeline, and the math changes fast. Scale back R&D. Slow AI projects. Seek capital elsewhere at higher costs. The executives running these buildouts sound nervous when you press them on contingencies. Most don't want to talk on the record.

OpenAI and Anthropic need Europe. Both frontier labs count the continent as a key market and a talent pipeline. Now imagine Brussels mandates "European AI" for sensitive sectors, waving the digital sovereignty flag. That growth avenue? Dead. And if regulators tighten data export rules? American AI firms couldn't train on European data unless they store it locally. But if local operations are restricted, that becomes impossible. A Catch-22 that leaves AI strategists at these companies feeling cornered.

The isolation could reduce training data quality and diversity for American developers. Competitors with global data access would gain an advantage.

And there's the human capital question. Google's AI research center in Paris. Microsoft's development offices in Ireland. Apple's European headquarters in Cork. In a hostile climate, work visas for American staff become harder to obtain. Local employees face uncertainty about whether their projects survive the next quarter. If this drags on, expect hiring freezes. Strategic projects get pulled back to U.S. soil. Europe loses tech talent opportunities. Innovation fragments.

Wall Street counts the cost

Europe contributes 20-30% of overseas earnings for major tech firms. You can think of those earnings as load-bearing walls in a building. Pull one out, and the structure doesn't just shrink. It sags.

Brad Setser at the Council on Foreign Relations put it bluntly: if Europe goes after the profit centers of U.S. multinationals, it means "lower global profits for U.S. companies, weaker stock-market valuations (especially in technology), and less capacity to invest in areas such as artificial intelligence." The exposure is structural and, for some companies, embarrassingly so. Apple keeps significant intellectual property in Ireland and books a large share of global profits there. Pharmaceutical companies route R&D through low-tax European jurisdictions. The Bazooka's provisions on taxes and regulatory scrutiny could squeeze these arrangements hard. Finance teams who built their tax strategies around European subsidiaries are suddenly defensive about decisions made years ago.

Here's a number that should worry Washington: European investors hold nearly $8 trillion in U.S. stocks and bonds. That's almost twice what the rest of the world holds combined. Trust erodes, fund managers in Frankfurt and London start trimming American exposure. That feedback loop could weaken the dollar and raise U.S. borrowing costs.

"Once those new non-U.S. relationships get made, it's very hard to change them," warns Mary Lovely at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. A break with Europe could open doors to Chinese cloud providers and homegrown European alternatives. Even if initially inferior, switching costs lock in alternatives over time. Market share lost might never return.

Bloomberg Economics estimates the tariffs alone could cut targeted countries' U.S. exports by up to 50%. Add the Bazooka's service restrictions, and American firms face the mirror image of that pain.

The appeasement that failed

Last July, the EU accepted a trade deal that many officials privately called humiliating. Duties on European products tripled to 15% while tariffs dropped to zero on American industrial goods. Draghi called it what it was: Europe came out weaker. Von der Leyen disagreed, publicly anyway, talking up the "clarity and stability" the deal supposedly brought.

Six months later, Trump's Greenland ultimatum blew that clarity apart.

"It is getting ridiculous this constant threat of tariffs," former EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom, who helped design the Anti-Coercion Instrument, wrote on X. "Time for Europe to stand up."

German industry, usually the first to counsel patience, has shifted. You can hear frustration breaking through the careful phrasing. Hildegard Müller at the VDA auto trade group wants "a smart, strategic response from Brussels." The costs of additional tariffs "would be enormous for German and European industry, especially in these already challenging times," she said. Bertram Kawlath, president of the German engineering association VDMA, dropped the diplomatic tone entirely: "If the EU gives in here, it will only encourage the US president to make the next ludicrous demand." These are executives who spent decades treating the transatlantic relationship as bedrock. Now they sound emboldened to fight.

European Parliament's major political groups have agreed to reject implementation of last year's tariff cuts on American industrial goods until Trump changes course. That's the conservatives, socialists, and liberals united. The gravity of the moment, in diplomatic terms, is hard to overstate.

Daily at 6am PST

Don't miss tomorrow's analysis

No breathless headlines. No "everything is changing" filler. Just who moved, what broke, and why it matters.

Free. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

The China problem nobody wants to discuss

An unintended beneficiary lurks in the background. If American tech gets locked out, Chinese firms long kept at arm's length over security concerns might find new openings.

Alibaba's cloud unit and Huawei have limited European footprints today. But they could market themselves as politically neutral alternatives. If you're a European procurement officer who just lost access to AWS, do you wait for a homegrown solution that doesn't exist yet, or do you take the call from Shenzhen? The choice would make many uncomfortable. Some would make it anyway.

"For the U.S., the eventual outcome could be selling less to Europe, denting profits and opening the door to competitors from countries like China," Lovely notes. Washington's larger strategic goal of countering Beijing would suffer a setback of its own making.

Bloomberg Opinion columnist Lionel Laurent captured the bitter irony: "If the status of American ally means being subjected to trade and technological subservience rather than being lavished with Cold War-style aid, cutting loose will become preferable."

What happens next

EU leaders plan to meet Thursday for an emergency summit. European Council President Antonio Costa said the bloc would "defend ourselves against any form of coercion." The Commission has four months to investigate once the ACI process begins, then member states have eight to ten weeks to approve countermeasures. Even just triggering an investigation sends a message.

The Bazooka remains holstered. For now.

German and Italian officials have cautioned against deploying it quickly. They worry about damaging the transatlantic relationship beyond repair, especially while Ukraine's security depends on Western unity. But the consensus around appeasement has cracked. Sweden's Kristersson: Europe won't be "blackmailed." Frederiksen in Copenhagen picked up the same word. It's spreading.

The shift runs deeper than trade policy. "People are starting to feel that the sense of humiliation, and vassalization, is at a point that is unacceptable," Jérémie Gallon, head of Europe for consulting firm McLarty Associates, told the Wall Street Journal. A YouGov poll Monday showed 67% of Britons back retaliatory tariffs if Trump proceeds.

Thursday's summit won't be comfortable. The officials walking into that Brussels room understand the stakes: they might be deciding whether to crack a 70-year alliance down the middle. Starmer, watching from outside the EU, called tariffs against allies "completely wrong" but wouldn't commit to retaliation. Britain sits outside the Bazooka's reach. Everyone else? Not so lucky.

For American tech executives, the worst-case scenario stays hypothetical. That's the line, anyway. Cooler heads, off-ramps, too much money at stake for anyone to actually pull the trigger.

But the fact that Europe created this weapon and now openly discusses aiming it at Washington changes the calculus permanently. The era of treating Europe as a guaranteed profit center may be ending. In its place could emerge a fragmented digital world where American firms negotiate access on Europe's terms or find themselves locked out entirely.

From Seattle to Silicon Valley, executives are watching Brussels and war-gaming contingencies. The servers in Spain and Denmark and Germany keep humming. The data centers aren't going anywhere yet. But everyone from cloud architects to Wall Street bankers is hoping the Bazooka stays where it is.

Because if it fires, nobody wins.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the EU's Anti-Coercion Instrument?

A: A trade-defense law adopted in 2023 that lets the EU retaliate against economic coercion by foreign powers. Unlike traditional tariffs, it can revoke business licenses, bar companies from government contracts, and suspend intellectual property protections across the 450-million-consumer single market.

Q: How much revenue do U.S. tech companies earn from Europe?

A: Europe contributes 20-30% of overseas earnings for major tech firms. Apple gets about 25% of net sales from Europe. Meta has 400 million European users. Google employs 7,000-plus in the UK alone. These revenues help finance AI infrastructure buildouts in the U.S.

Q: What triggered the current EU-US trade tensions?

A: Trump announced 10% tariffs on eight European countries starting February 1, escalating to 25% by June, unless Denmark agrees to sell Greenland. European leaders rejected the demand, calling it "blackmail," and are now considering deploying the Anti-Coercion Instrument in response.

Q: How long would it take the EU to deploy the Bazooka?

A: The Commission has four months to investigate once the process begins, then member states have eight to ten weeks to approve countermeasures. However, simply triggering an investigation sends a strong political signal that the EU is willing to escalate.

Q: Who benefits if U.S. tech gets locked out of Europe?

A: Chinese cloud providers like Alibaba and Huawei could market themselves as alternatives. European procurement officers who lose access to AWS or Azure might take calls from Shenzhen. This would undermine Washington's broader strategic goal of countering Beijing's tech influence.

Related Stories