The uncomfortable part for anyone planning to buy a laptop, upgrade a server, or manufacture smartphones in 2026 isn't that memory chips are expensive. It's that the shortage driving those prices has nothing to do with production capacity failing to meet normal demand. The global semiconductor industry can make plenty of chips. It's choosing not to make the ones most people need.

Walk into Tokyo's Akihabara district. Retailers are rationing memory now. Eight products per customer. That's it. A 32GB DDR5 kit? $113 (€108) in October. Today it's $313 (€298). Shelves are one-third empty. These aren't supply chain hiccups. This is what happens when an entire industry pivots to serve a single customer class: hyperscalers building AI infrastructure. Everyone else gets whatever's left over.

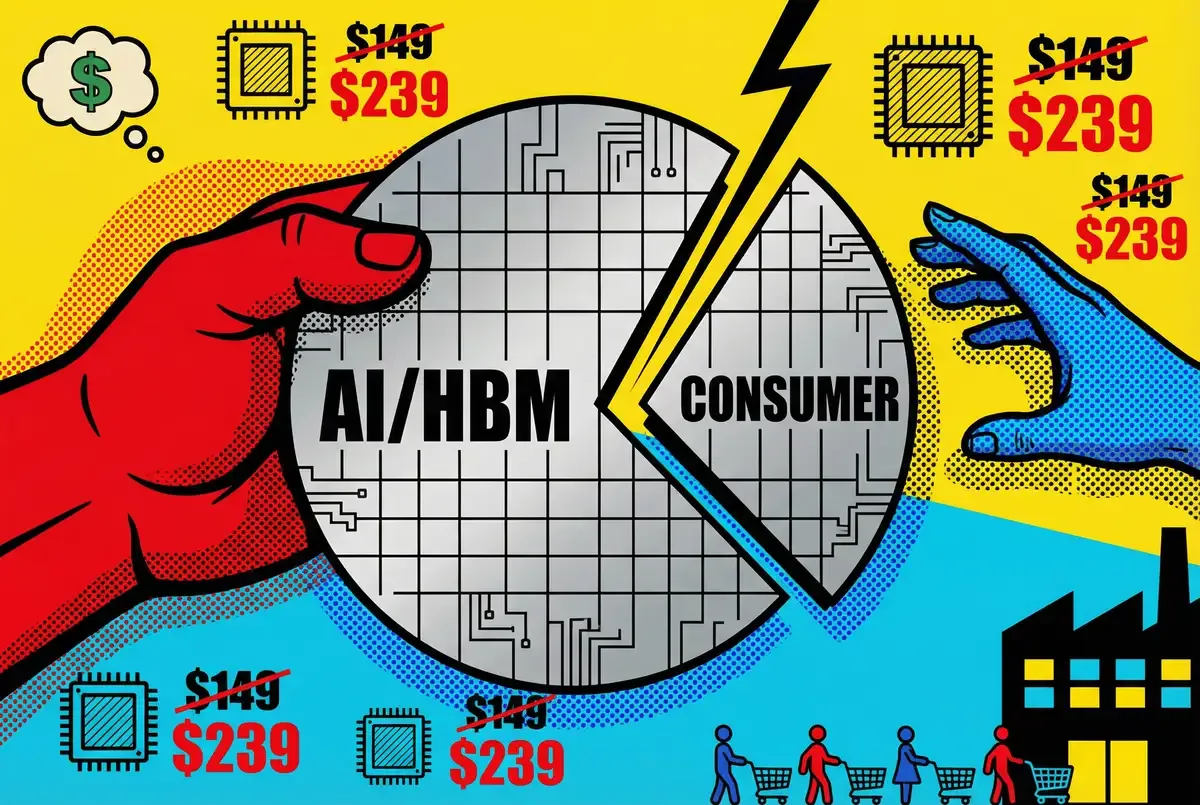

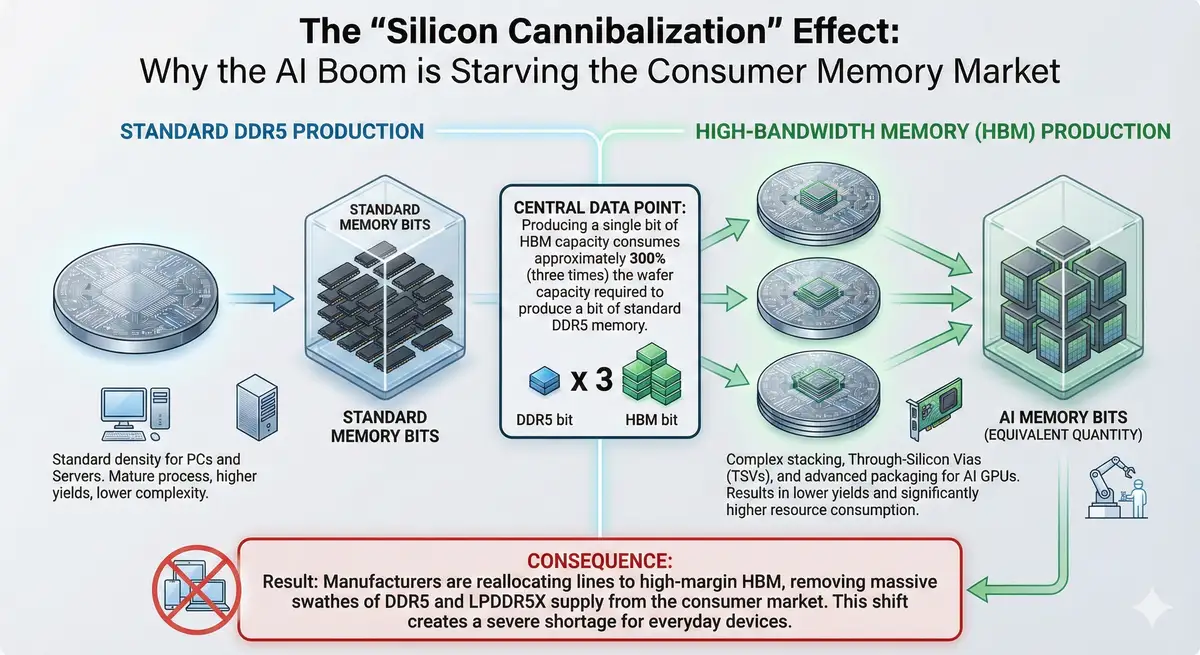

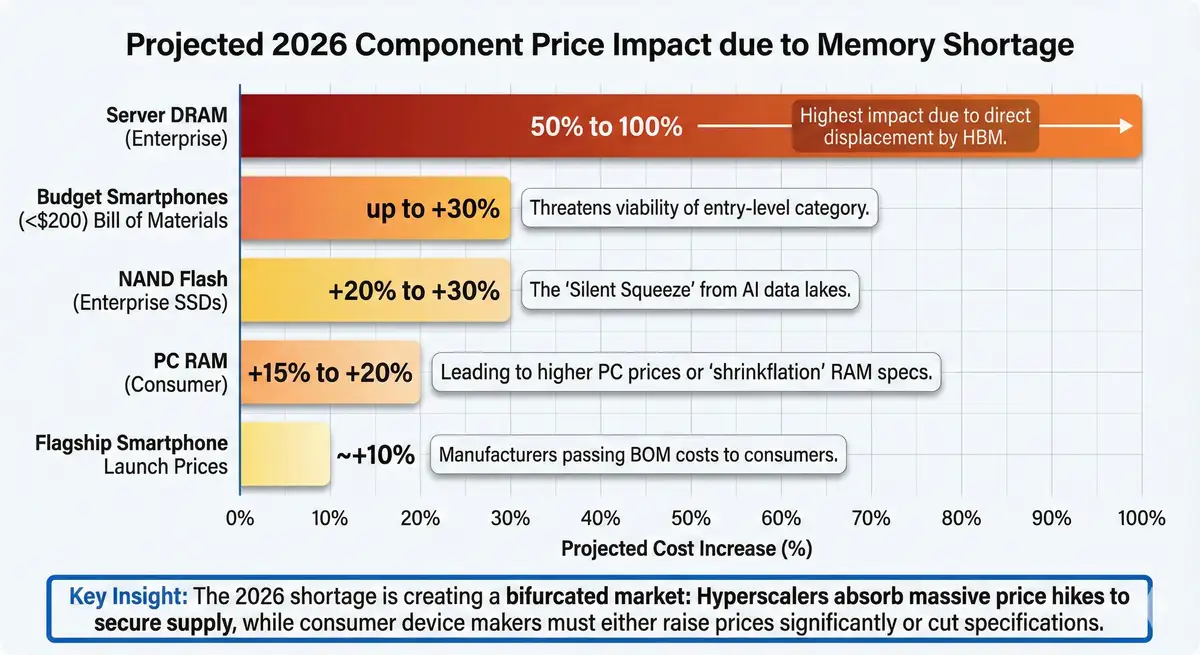

The memory shortage of 2026 marks an inflection point. For the first time in semiconductor history, a new technology wave isn't creating shared prosperity—it's actively cannibalizing existing supply chains to feed itself. Artificial intelligence requires specialized high-bandwidth memory (HBM) that consumes roughly three times the manufacturing capacity of standard memory chips. Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron are chasing AI margins. They've systematically starved conventional memory production. The result is a bifurcated market where data center operators pay premiums to secure allocation while consumers face price increases of 50-100% for the same components that were abundant a year ago.

This isn't temporary. New fabrication plants take years to build. Significant relief won't arrive until 2027 or 2028, when facilities currently under construction begin volume production. The semiconductor industry has split into two non-interoperable economies. The AI supercycle runs on unlimited capital. Everyone else competes for scraps.

Key Takeaways

• Memory manufacturers shifted capacity to AI-focused HBM chips, consuming 300% more wafer area than standard DRAM, creating severe shortages through 2027.

• Consumer memory prices surged 50-100% with server modules jumping from $149 to $239 in two months, as Samsung hiked prices 60% without warning.

• Glass substrate technology emerges as critical advantage for 2027, with Absolics, Intel, and Samsung racing to commercialize production for AI accelerators.

• New fab capacity won't arrive until 2027-2028, with SK Hynix investing $500-600 billion and TSMC accelerating Arizona production under CHIPS Act.

The displacement mathematics

Understanding the shortage requires understanding silicon wafer economics. Think of it like farmland allocation. You can plant wheat or you can plant orchids. The orchids sell for ten times the price. But they need a greenhouse occupying three acres of arable land. The wheat never gets planted.

Producing one bit of HBM capacity consumes approximately 300% of the wafer area needed for standard DDR5 memory. This multiplier stems from HBM's complex architecture—multiple memory dies stacked vertically and connected through microscopic through-silicon vias, then packaged alongside AI accelerators. The manufacturing process is technically demanding, yields are lower, and each chip requires substantially more physical space on the production wafer.

Memory manufacturers face a stark choice. They can produce HBM and sell it to hyperscalers at premium prices, or they can produce commodity DRAM for PCs and smartphones at commodity margins. The economics aren't subtle. By late 2025, major DRAM capacity had shifted to HBM3e production. The upcoming HBM4 generation absorbed even more. Samsung told customers it would cease production of certain older DDR4 chips. Focus on newer memory instead. Micron signaled it would stop shipping DDR4 and mobile LPDDR4 within months. China's ChangXin Memory Technologies followed.

The timing proved catastrophic. This pivot hit just as demand for PCs, data centers, and smartphones rebounded. All of which still rely on conventional memory. Average DRAM inventory at suppliers? Over 13 weeks in late 2024. By October 2025? Barely 2-4 weeks. Memory makers were effectively sold out of certain products well into 2026 by year's end. SK Hynix told analysts the shortfall would likely persist through late 2027.

Contract prices reflect the imbalance. Take a 32GB DDR5 server module. September: $149 (€142). November: $239 (€227). Samsung didn't announce the hike. They just did it—certain chips up 60% compared to September. The analysts watching this now say DRAM could climb another 20% by early 2026. Some server configurations might double by year-end. "The price premiums being paid are extreme," says Tobey Gonnerman, president of distributor Fusion Worldwide.

SK Group chairman Chey Tae-won described the situation candidly at a Seoul event in November: "These days, we're receiving requests for memory supplies from so many companies that we're worried how we'll handle them. If we fail to supply them, they could face a situation where they can't do business at all." Competitors and customers globally are effectively begging for supply.

Get Implicator.ai in your inbox

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

What conventional coverage misses is that this isn't scarcity in the traditional sense. Global wafer production capacity hasn't collapsed. Fabs aren't sitting idle. The industry is simply manufacturing different products—ones that serve fewer customers at higher margins. For every HBM stack destined for an Nvidia GPU, millions of potential smartphone or PC memory modules vanish from the supply chain. It's displacement, not shortage. The distinction matters.

The glass substrate gambit

Memory prices dominate headlines. But a quieter shift is changing who wins in semiconductor packaging. Glass substrates for advanced chip packaging. The most significant material science transition in decades.

Traditional organic substrates—essentially sophisticated circuit boards made from plastic composites—have hit physical limits. They warp under thermal stress from massive AI processors, breaking microscopic connections. They can't support the interconnect density that next-generation chiplet architectures demand. And they're opaque. That precludes future innovations like co-packaged optics where data travels through substrates as light rather than electricity.

Glass solves these problems. It's rigid, allowing larger package sizes without warping. It enables interconnect densities roughly 10 times higher than organic materials. Critically, it's transparent—opening pathways to photonic integration that could eliminate bandwidth bottlenecks in AI clusters by 2027.

The race to commercialize glass substrate manufacturing is fierce. Absolics, a subsidiary of South Korean materials giant SKC, has positioned itself as the U.S. frontrunner. Its facility in Covington, Georgia—backed by $75 million (€71 million) in CHIPS Act funding—is ramping high-volume production throughout 2026. The company has moved beyond pilot production. Reportedly nearing pre-qualification with major customers including AMD and Amazon Web Services. Initial capacity targets 12,000 square meters of glass substrate, with aggressive scaling planned.

Intel pioneered glass substrate R&D. Then financial pressures from its turnaround hit. Now the company is embracing outsourcing rather than building its own mass production lines. This lets Intel integrate the technology without shouldering massive capital expenditure alone. For the foundry business Intel is trying to build, glass-ready packaging by 2026-2027 might distinguish its services. Or it might not. Pure-play competitors aren't standing still.

Samsung moved fast. Samsung Electro-Mechanics accelerated its roadmap. Mass production starts in 2026. The move puts them in direct conflict with Intel and TSMC. But Samsung has a card the others can't play: they make the memory, the logic, and the packaging. One roof. No fragmentation. That matters to customers worried about supply chain complexity.

The challenge is yield. Glass breaks. Handling large panels in high-volume factories without breakage—that requires specialized equipment and processes nobody's perfected yet. The learning curve in 2026 will produce variable yields. Initial supply of glass-packaged chips gets limited to only the highest-margin AI server applications. Equipment shortages compound the problem. Cutting glass without micro-cracks demands specialized laser-induced deep etching tools. Companies like LPKF represent critical chokepoints in the supply chain.

The strategic implications extend beyond manufacturing challenges. Glass substrates will likely arrive at meaningful scale in 2027, just as some conventional packaging capacity begins to ease. The companies that master glass manufacturing first will capture premium contracts for next-generation AI accelerators. Those that lag risk marginalization in the highest-growth segment of the semiconductor market.

Casualties of the AI tax

For consumers and businesses outside the AI infrastructure boom, 2026 represents a year of difficult trade-offs. The memory shortage is forcing PC manufacturers into unprecedented defensive strategies. Major vendors like Dell and Lenovo have signaled price increases of 15-20% taking effect in early 2026. Some system integrators have begun offering configurations without RAM—a "shrinkflation" tactic that keeps advertised prices artificially low while forcing you to source expensive modules in a volatile spot market.

The International Data Corporation warns the PC market could shrink by 5-9% in 2026 compared to expectations. Specifically because soaring memory costs are deterring buyers. Under a pessimistic scenario, average PC selling prices could jump 6-8% as manufacturers pass costs downstream. What should have been a boom year—millions of users facing Windows 10 end-of-support deadlines—may turn into a slump as consumers balk at inflated prices.

The irony deepens for so-called "AI PCs." Laptops with built-in AI coprocessors? They need more memory. 16GB at minimum. Often 32GB or more. Precisely when memory is scarce and expensive. If you're waiting for an affordable AI PC, prepare to wait.

Smartphone manufacturers face similar pressures. Memory and flash storage comprise significant portions of a phone's bill of materials. Component prices are climbing. Manufacturers have unappealing options: raise handset prices, reduce memory specifications, or absorb margin hits. Xiaomi and Realme have signaled price increases are coming. "The steep increases in memory costs are unprecedented since the advent of smartphones," Realme India executive Francis Wong told Reuters. Handset prices might need to rise 20-30% by mid-2026, he suggested.

Some manufacturers will attempt cost reductions elsewhere. Cheaper cameras or processors. But "the cost of storage is something all manufacturers must absorb; there's no way to avoid it," Wong said. Mid-range devices that had begun offering flagship-level RAM and storage may regress to lower specifications to remain affordable. You could face longer upgrade cycles, hanging onto older phones if new models deliver fewer improvements at higher prices.

Enterprise customers aren't insulated. Cloud operators are bleeding money to secure memory chips and GPUs. AI infrastructure spending? Up over 50% in 2024. Thus far, hyperscalers have deep enough pockets to shoulder price spikes. Evidenced by open-ended orders to suppliers with instructions to ship everything they can manufacture regardless of price. But if memory costs continue climbing, cloud providers may eventually pass increases downstream. Higher service pricing or slower rollout of new capabilities.

The shortage is redistributing market power in ways that favor concentration. PC makers with scale and long-term contracts—Dell, HP, Lenovo—can weather this. Small regional builders or DIY retailers without leverage? They're facing allocation cuts already. Potential consolidation or exit. In the AI startup ecosystem, only firms with strong funding can afford inflated GPU prices or multi-month queues for cloud access. The well-capitalized survive. Cash-strapped startups? Structural disadvantage. Smaller competitors face a choice: find deep pockets fast or exit the market entirely.

The timeline problem

Relief is theoretically approaching. Though don't hold your breath. Samsung and SK Hynix plan HBM4 mass production starting February 2026. Ramp-up continues through the year. HBM4 offers bandwidth improvements—double what HBM3E delivered. Power consumption drops 40%. Nvidia needs this for Rubin, its next-generation AI accelerator launching second half of 2026.

But conventional memory capacity? Different story entirely. SK Hynix just committed $500-600 billion (€475-570 billion) to a new semiconductor cluster in Yongin, South Korea. First facility comes online May 2027. This plant targets conventional DRAM and mature-node products—the chips consumer electronics manufacturers actually need. Samsung pursues similar expansion. Construction timelines push significant capacity into 2027-2028.

TSMC is accelerating U.S. manufacturing under the CHIPS Act. The company's first Arizona facility is producing 4-nanometer chips at near-full capacity. Apple, AMD, Qualcomm, Broadcom, and Nvidia already placing orders. A second Arizona fab begins equipment installation in October 2026. Volume production targeted for Q4 2027. A third facility breaks ground in 2026. The geopolitical calculation is clear: domestic semiconductor manufacturing is now strategic priority.

Sign up for Implicator.ai

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. Clear reporting on power, money, and policy. Delivered daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Micron's expansion plans hit headwinds. New York megafabs got delayed. Two to three years. Groundbreaking shifts to Q2 2026. Volume production? Now 2028 or later. This delay worsens memory market pressure and highlights challenges of building leading-edge fabs in the United States. The task requires capital, yes. But also specialized technical talent and supply chain infrastructure that migrated overseas over decades.

Industry analysts mostly agree on timing. Acute shortage persists through the first half of 2026 at minimum. Normalization before 2027-2028? Unlikely. Team Group, a major memory module manufacturer, warned that distribution stockpiles exhaust by Q1 2026. After which "allocation could become difficult regardless of willingness to pay." Even as manufacturers commit capital to new facilities, lead times for cleanroom construction and equipment installation mean new capacity typically requires 2-3 years from groundbreaking to full production.

Price trajectories offer nuanced pictures. Under optimistic scenarios, DRAM prices could decline modestly from their 2026 peak beginning in late Q3. Gradual normalization through 2027. Under pessimistic scenarios—unexpected AI market cooling or demand moderation—memory oversupply could emerge in 2027. Triggering sharp price collapse similar to previous cycles.

The challenge for executives and planners is that uncertainty cuts both ways. Some analysts warn the current shortage could extend well into 2027 or beyond. SK Hynix guidance suggesting undersupply persisting until late 2027. Others contend the market bifurcation—AI infrastructure commanding premium prices while consumer devices face scarcity—represents structural shift rather than temporary dislocation.

The geopolitical subplot

Beyond immediate supply crisis, the memory shortage is accelerating realignment of global semiconductor manufacturing. One that's been gestating for years. The United States largely ceded advanced chip manufacturing to Taiwan and South Korea over two decades. Now racing to rebuild domestic capacity through massive CHIPS Act subsidies. TSMC's Arizona facilities produce chips for Apple, AMD, and Nvidia. Advanced U.S. chip design is coming back into domestic production for the first time in years.

This shift reflects risks Washington now takes seriously. Concentrating advanced semiconductor production in Taiwan creates vulnerabilities. A self-governing island whose political status remains contested. TSMC's Arizona capacity meets only about 7% of U.S. chip demand currently. But the trajectory is clear. Domestic manufacturing will play larger roles in securing supply for technologies the government deems critical.

Samsung's Taylor, Texas facility pivoted directly to 2-nanometer production. Late 2026 target. Strategic thinking similar to TSMC's Arizona bet. If successful, Samsung gets U.S. manufacturing foothold complementing Korean operations. For Micron, New York delays represent setbacks in this geopolitical competition. Though the company remains committed to expanding U.S. capacity.

A quieter crisis is paralyzing automotive and industrial sectors. The Dutch government moved to seize control of Nexperia—a Chinese-owned manufacturer of essential discrete components—due to security concerns. Beijing retaliated with export controls. Chip flows from Chinese assembly plants to Western customers effectively severed. Major European automakers? Volkswagen, BMW, Mercedes-Benz. They're terrified.

Assembly line stoppages aren't theoretical for German auto executives. They're losing sleep over this. A modern vehicle requires thousands of cheap discrete components. Transistors, diodes, MOSFETs that Nexperia manufactures. Without a specific 50-cent (€0.48) power management chip, a $50,000 (€47,500) electric vehicle cannot be completed. Unlike logic chips, these components aren't easily swappable. Validating a new supplier for automotive safety standards takes 6-12 months. The 2026 shortage is locked in regardless of what happens next in trade negotiations.

The situation illustrates a "K-shaped" recovery in semiconductors. The AI and high-performance computing sectors soar on unlimited capital and priority access to advanced nodes. Automotive and industrial sectors face a recessionary environment. Shortages, geopolitical friction, and "legacy" nodes being ignored by fabs chasing AI margins. While fears exist of China flooding markets with mature-node chips, trade barriers and bifurcating standards mean Western automakers cannot easily access Chinese surplus to offset losses. The market is splitting into two non-interoperable spheres.

What happens next

The 2025-2026 memory shortage proves something uncomfortable about artificial intelligence. For all the talk about transformation and potential, AI infrastructure still depends on mundane physical constraints. Chips that store data. The rush to secure AI leadership has made policymakers and executives suddenly aware that semiconductor supply chains represent chokepoints they can't code around.

The shortage has governments reconsidering decades of outsourcing strategy. Chip manufacturing is coming home, backed by massive subsidies. Whether domestic capacity proves adequate—that remains an open question. The CHIPS Act money is real. The timelines are long.

Technology investments in 2026 require new math. Elevated costs, yes. But also lead times stretching months longer than standard procurement cycles. Trade-offs between performance, capacity, and affordability that executives haven't faced in years. Cheap, abundant memory? That era ended. At least for the next 18 months, possibly longer. Only when new semiconductor plants come online will markets return to something resembling stable footing.

Until then, memory chips have become the commodity that determines who builds what and when. Industries that thought themselves immune to hardware constraints are discovering otherwise. The AI boom everyone celebrates is actively cannibalizing supply chains for everything else. That's not a bug. It's the business model.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why does HBM take 3x more manufacturing capacity than regular memory?

A: HBM stacks multiple memory dies vertically and connects them through microscopic through-silicon vias, then packages them alongside AI accelerators. This complex architecture requires significantly more wafer area per bit of capacity, lower yields due to manufacturing difficulty, and specialized packaging equipment. Regular DDR5 memory uses simple, flat chips that are easier and cheaper to produce at scale.

Q: Can I still upgrade my PC or laptop in 2026? What should I expect?

A: Yes, but expect to pay 50-100% more than 2024 prices. Memory will be available but scarce, with retailers potentially implementing purchase limits. PC makers with contracts (Dell, HP, Lenovo) will have better access than small builders. If you're planning upgrades, buy memory early in 2026 before Q2 when distribution stockpiles are expected to exhaust completely.

Q: Why can't memory makers just build more factories to solve this faster?

A: Building a modern semiconductor fab takes 2-3 years from groundbreaking to volume production. Cleanroom construction, equipment installation, and process qualification can't be rushed. SK Hynix's new $500-600 billion cluster won't produce chips until May 2027. Micron's delayed New York fabs now target 2028. The physics and complexity of advanced manufacturing impose hard time limits that money can't overcome.

Q: What exactly are glass substrates and why do they matter for AI chips?

A: Glass substrates replace plastic-based circuit boards in advanced chip packaging. Glass doesn't warp under thermal stress from massive AI processors, enables 10x denser interconnects than organic materials, and is transparent—allowing future photonic integration where data travels as light rather than electricity. Companies mastering glass production by 2027 will capture premium contracts for next-generation AI accelerators worth billions in revenue.

Q: If AI demand crashes, will memory prices collapse like previous cycles?

A: Likely yes. Memory markets historically follow boom-bust cycles. If AI investments hit diminishing returns or economic conditions worsen, the breakneck spending could pause suddenly. New fab capacity coming online in 2027-2028 would then create oversupply, potentially triggering sharp price collapse. However, manufacturers are betting AI represents a permanent platform shift rather than a temporary bubble like crypto mining.