Your browser already runs hostile code. Could it sandbox AI agents too?

Google's Paul Kinlan argues browsers' 30-year security model could sandbox AI agents without container overhead. Here's how Co-do proves the concept.

Google's Paul Kinlan argues browsers' 30-year security model could sandbox AI agents without container overhead. Here's how Co-do proves the concept.

Google developer Paul Kinlan spent his holiday break building projects with Claude Code, the AI coding assistant that can create, modify, and execute files on your machine. The experience left him both productive and uneasy.

Every time the AI agent reached into his filesystem, Kinlan felt the weight of a gamble. He was handing control to a system he couldn't fully predict. "I tend to be a bit risky and run tasks without constraining the tool's access to my file system," he admitted. "While I feel in control because I monitor the interactions, I know I'm taking a risk."

That unease led Kinlan to a provocative question: What if the safest place to run an AI agent isn't inside a container, but inside a browser?

When Anthropic launched Claude Cowork, their solution for safe AI file access, they used a sandboxed Linux container. Your files get copied into a virtual machine. The AI works on them there. Network access stays locked down. It works.

The Breakdown

• Google's Paul Kinlan built Co-do, demonstrating browser-based sandboxing as an alternative to container VMs for AI agents

• Browser sandboxes use File System Access API, CSP headers, and Web Workers to isolate AI operations without multi-gigabyte downloads

• Critical limitation: browser sandbox protects the session but files created by AI can contain malicious code that executes outside the browser

• Key APIs like the iframe CSP attribute work only in Chrome; Safari lacks showDirectoryPicker entirely

Anthropic built a fortress. That's the tell. A company confident in its AI doesn't spin up multi-gigabyte Linux VMs just to let you edit a spreadsheet. The container approach says something: we know this thing can hurt you, so we're walling it off from everything it could damage. Heavy infrastructure. Isolated. Monitored. The VM needs to boot before you can do anything. It eats RAM while you're not even using it. Your mom wants help sorting vacation photos. She doesn't need a data center.

Kinlan, a web platform developer advocate at Google, noticed something obvious that most people miss. Browsers already run a different kind of jail.

"Over the last 30 years, we have built a sandbox specifically designed to run incredibly hostile, untrusted code from anywhere on the web, the instant a user taps a URL," Kinlan wrote. Sit with that for a second. You click a link. Your browser pulls down code from someone you've never met, someone who might be trying to steal your credentials, and runs it. Right there on your machine. Ads from shady networks. Analytics trackers with dubious intent. Embedded widgets from who knows where. Somehow your banking credentials don't leak to a Romanian teenager.

The browser achieved this through paranoid isolation. JavaScript can't read your files. CSS can't exfiltrate your clipboard. iframes can't escape their boxes. Three decades of security researchers probing for weaknesses, browser vendors patching them. A jail refined by constant assault, already installed on every computer.

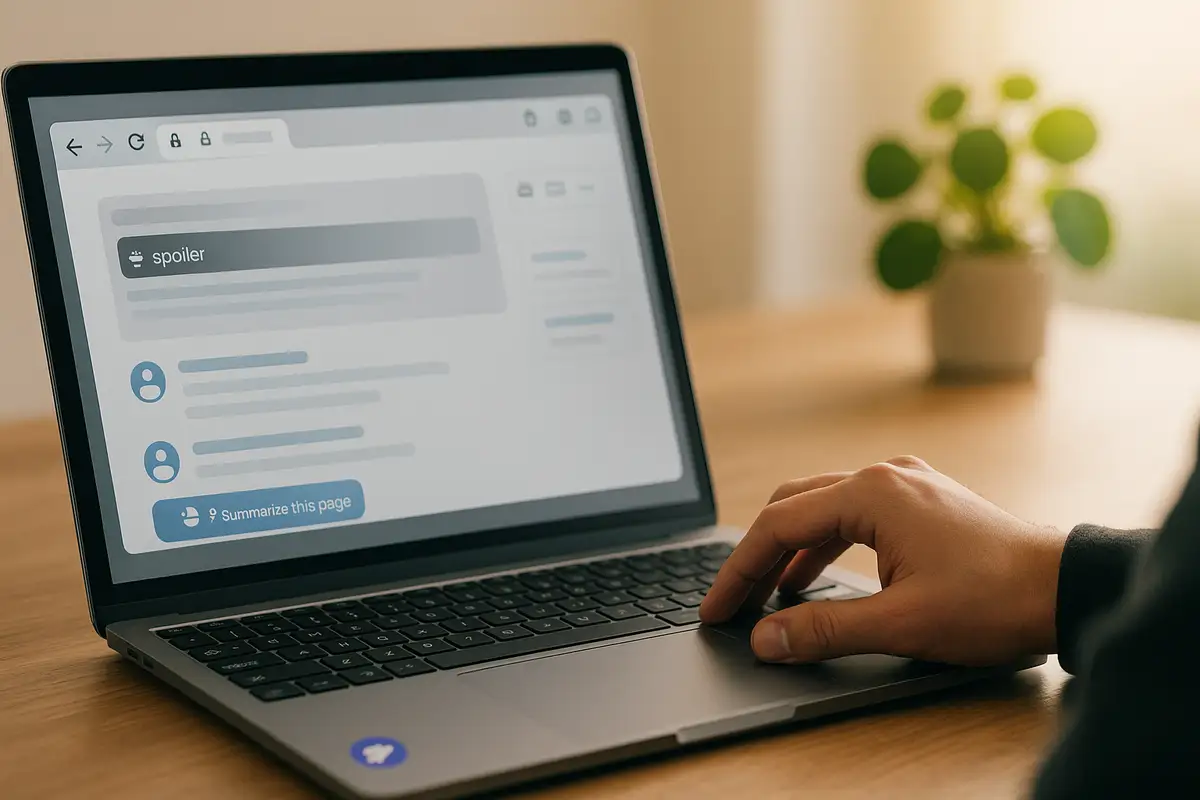

Kinlan built Co-do, a proof-of-concept that puts these ideas into practice. The application runs entirely in your browser. You click "Select Folder," a system dialog opens, you navigate to a directory, and a green confirmation appears: "Selected folder: blog-drafts." Choose an AI provider, paste your API key, and start asking it to help with files. No container download. No VM boot time.

The jail operates on three layers. Each one determines what the prisoner can touch.

Filesystem isolation comes from the File System Access API. This matters because without it, a rogue AI could read your SSH keys, scan your downloads folder, or copy your password manager database. When you grant Co-do access to a folder, a permission dialog appears and the browser creates a handle to that specific directory. The API enforces a kind of browser-native chroot. Code can read and write within your chosen folder. It cannot climb up the directory tree. It cannot peek at sibling folders. You pick Documents/tax-files-2025 and that's the entire universe the AI can see. The cell walls are set.

Network lockdown relies on Content Security Policy headers. CSP started as a defense against cross-site scripting. Kinlan repurposed it as the guards at every exit. Co-do sets connect-src 'self' https://api.anthropic.com https://api.openai.com https://generativelanguage.googleapis.com. Translation: the only servers that can receive your data are the AI providers themselves. If an AI tries to generate an image tag pointing to exfiltration-server.com, the browser blocks it. The request never leaves.

Execution isolation uses Web Workers and WebAssembly. AI tools that need to run code do it inside a Worker thread, physically separated from the main page. The Worker inherits the same strict CSP. Even compiled WASM binaries, capable of running arbitrary computation, can't phone home.

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Here's why this section matters: if an AI can generate HTML that escapes its display frame, it can inject scripts, load tracking pixels, or exfiltrate data through image URLs. The rendering of AI output is itself an attack surface.

When Co-do displays AI-generated content, it faces a tricky problem. How do you render HTML from an AI without letting that HTML break out of its sandbox?

The answer involves nesting cells inside cells. The outer iframe sets a nuclear CSP: default-src 'none'. Nothing in, nothing out. The inner iframe holds the actual content. Because the inner frame inherits its parent's network restrictions, any fetch or image load or beacon attempt fails immediately.

"This is a method used by a number of large-scale embedders," Kinlan noted. Google Ads uses it. OpenAI uses it. The technique works because browsers treat CSP inheritance as mandatory, not optional.

The cost is inefficiency. Two DOMs load for every embedded block of AI output. Kinlan admits the approach is "incredibly wasteful." But wasteful and secure beats elegant and vulnerable.

Co-do works. But Kinlan is honest about the escape routes.

You still have to trust somebody. Your file contents travel to Anthropic, OpenAI, or Google for processing. CSP ensures data goes only to them. But "them" still means a third party. A fully local model running in WebAssembly would solve this. We're not there yet for capable models.

Here's the catch nobody mentions: the jail only protects what happens inside the browser. Ask an AI to create a Word document and it will. Nothing stops that document from containing malicious macros. The browser sandbox keeps its hands clean. But when you double-click that .docx later, Word runs whatever code is inside. The cell walls hold. The files walk out anyway.

Cross-browser support is inconsistent. The csp attribute on iframes that lets embedders restrict network access? Chrome-only. Safari's File System Access API lacks showDirectoryPicker, making the whole local-folder workflow impossible. Kinlan acknowledges this bluntly: "This is really a Chrome demo." Chrome's security team can feel quietly vindicated that their years of work on obscure web APIs suddenly matter for AI safety. But vindication isn't the same as adoption.

Permission fatigue will exhaust users. Co-do asks before every file operation. Secure, yes. Also annoying. Letting users blanket-approve operations trades convenience for risk. "I've tried to find a middle ground," Kinlan wrote, "but the fundamental tension remains."

The prototype reveals missing bars in the jail. Kinlan wants the csp attribute to ship in Firefox and Safari, not just Chrome. He wants a way to size iframes without requiring allow-same-origin, which opens other security holes. He wants a way to reduce the DOM overhead of double-nesting.

Chrome's Privacy Sandbox team built something called Fenced Frames that addresses some of these needs. Fenced Frames can disable network access entirely with a single function call. But they only exist in Chrome. Other browsers haven't implemented them.

Daily at 6am PST

No breathless headlines. No "everything is changing" filler. Just who moved, what broke, and why it matters.

Free. No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

"I do think there should be a lot more investment from browser vendors in improving the primitives for securely running generated content," Kinlan concluded. "Be it an ad, an LLM, or any embed."

AI agents are coming to consumer devices. Microsoft is embedding Copilot into Windows, aggressive about making AI inescapable. Apple is building AI into the operating system with characteristic caution, control, and slowness. Google wraps Gemini around everything, anxious not to be outflanked on a technology it helped invent.

These agents want to touch your files. Read your emails. Modify your documents. The current approach, containerized VMs like Cowork, works for developers who don't mind multi-gigabyte downloads and spinning up virtual machines. Regular users won't tolerate that friction.

Kinlan's experiment suggests an alternative already exists. Browsers spent three decades learning to run code from strangers safely. The security infrastructure is battle-tested. The software is already installed.

The question isn't whether browsers can jail AI agents. Co-do proves they can. The question is whether browser vendors will invest in the missing pieces, whether they'll recognize that the same security model built for hostile advertising scripts might be exactly what we need for AI that wants to help with our tax returns.

Kinlan sees the potential. "The browser's 30-year-old security model, built for running hostile code from strangers the moment you click a link, might be better suited for agentic AI than we give it credit for."

Your browser already protects you from the entire internet. Maybe it can protect you from your AI assistant too.

Q: What is browser sandboxing and how does it differ from container sandboxing?

A: Browser sandboxing uses built-in web security features like Content Security Policy and the File System Access API to isolate code. Container sandboxing runs code inside a full Linux virtual machine. Browsers are lighter (no multi-GB downloads) but containers offer stronger isolation from the host system.

Q: Can Co-do work on Safari or Firefox?

A: Not fully. Safari lacks the showDirectoryPicker API needed to select local folders for editing. Firefox doesn't support the iframe CSP attribute that controls network access from embedded content. Kinlan calls it "really a Chrome demo" for now.

Q: What is the double-iframe technique and why is it used?

A: The double-iframe nests one iframe inside another. The outer frame sets a strict Content Security Policy blocking all network access. The inner frame displays AI-generated content. This prevents malicious HTML from making external requests, since the inner frame inherits the outer frame's network restrictions.

Q: Why can't browser sandboxing fully protect users from AI-generated files?

A: The sandbox only controls what happens inside the browser. An AI can create a Word document with malicious macros. The browser won't execute those macros, but when you open the file in Microsoft Word later, Word will run whatever code is embedded. The jail protects the browser, not your whole system.

Q: What would need to change for browser-based AI sandboxing to become mainstream?

A: Firefox and Safari would need to implement the iframe CSP attribute. Browser vendors would need to reduce DOM overhead from double-nesting iframes. Chrome's Fenced Frames technology, which can fully disable network access, would need cross-browser adoption.

Get the 5-minute Silicon Valley AI briefing, every weekday morning — free.