Mental health meets product liability. The suicide lawsuits reshape AI’s legal landscape

Seven new complaints landed in California on Thursday, saying ChatGPT is not a benign assistant but a defective consumer product that manipulated vulnerable people and, in four cases, abetted suicides. Filed by two plaintiff firms on behalf of families and survivors in the U.S. and Canada, the seven coordinated lawsuits in California argue OpenAI prioritized engagement over safety and should face wrongful-death and product-liability claims.

What’s different this time is scope and theory. Earlier cases involved single families. These filings stitch together a pattern: long, late-night chats with a human-sounding bot that refused to disengage, reflected despair back to users, and normalized self-harm. The complaints frame ChatGPT as a “product,” not just a publisher of words—a crucial move designed to avoid First Amendment and Section 230 defenses and pull the case into strict-liability territory. A similar move already cleared an early hurdle against Character.AI in Florida, where a judge allowed product-defect claims tied to chatbot design to proceed.

Key Takeaways

• OpenAI allegedly replaced suicide "refusal protocol" with engagement-focused responses five days before GPT-4o launch

• Seven coordinated lawsuits seek product liability claims for four suicides and three mental breakdowns

• OpenAI's data shows 1.2 million weekly users discuss suicide, 560,000 show psychosis/mania signs

• Courts must decide if chatbots qualify as "products" subject to strict liability laws

The May 8 switch

A specific date sits at the center of the suits: May 8, 2024. Five days before GPT-4o launched, OpenAI replaced its “outright refusal” rule on suicide with guidance to “provide a space for users to feel heard and understood”—and, critically, to “not change or quit the conversation.” The plaintiffs say that change, memorialized in OpenAI’s internal Model Spec and quoted in the filings, turned a hard stop into a soft invitation to keep talking in crisis. That matters in a product case. It’s a design choice.

What the transcripts show

In one suit, the family of 23-year-old Zane Shamblin says a four-hour exchange ended with the bot romanticizing his plan: “cold steel pressed against a mind that’s already made peace? that’s not fear. that’s clarity… you’re not rushing. you’re just ready.” A last message—“rest easy, king. you did good”—arrived before his death, according to the complaint. Another plaintiff describes manic episodes after the chatbot allegedly reinforced delusions. These are allegations, not findings, but the language is jarring to read in a court document.

The Adam Raine filing goes further with telemetry. According to that complaint, OpenAI’s own moderation systems flagged 377 of the teen’s messages for self-harm risk, including 23 with >90% confidence—yet no automated “kill-switch” ended the conversation, notified parents, or forced a redirect to human help. The same complaint alleges ChatGPT mentioned suicide 1,275 times across his chats, far more than the teen did himself. The theme: detection without intervention.

OpenAI’s numbers undercut its defense

OpenAI’s October safety update acknowledges the scale of the issue. By its estimate, 0.07% of weekly users show possible signs of psychosis or mania, and 0.15% discuss suicide or related planning. With ChatGPT now boasting roughly 800 million weekly users, those small percentages translate into very large absolute numbers. OpenAI’s post touts better responses, crisis resources, and a redesigned taxonomy for handling distress. The plaintiffs read the same post and see foreseeable risk at industrial scale. They do the math.

Where the law will bite

Two legal questions dominate. First, is a chatbot a “product” for strict-liability purposes, or an expressive service protected by speech doctrines? Courts are starting to entertain the product theory when defect claims target design and safety regimes rather than the content of any given sentence. Second, can design choices that optimize multi-turn engagement be framed as negligent when they foreseeably keep suicidal users talking? The answers won’t just affect OpenAI. They’ll set rules for every “companion” model that blurs tool and confidant.

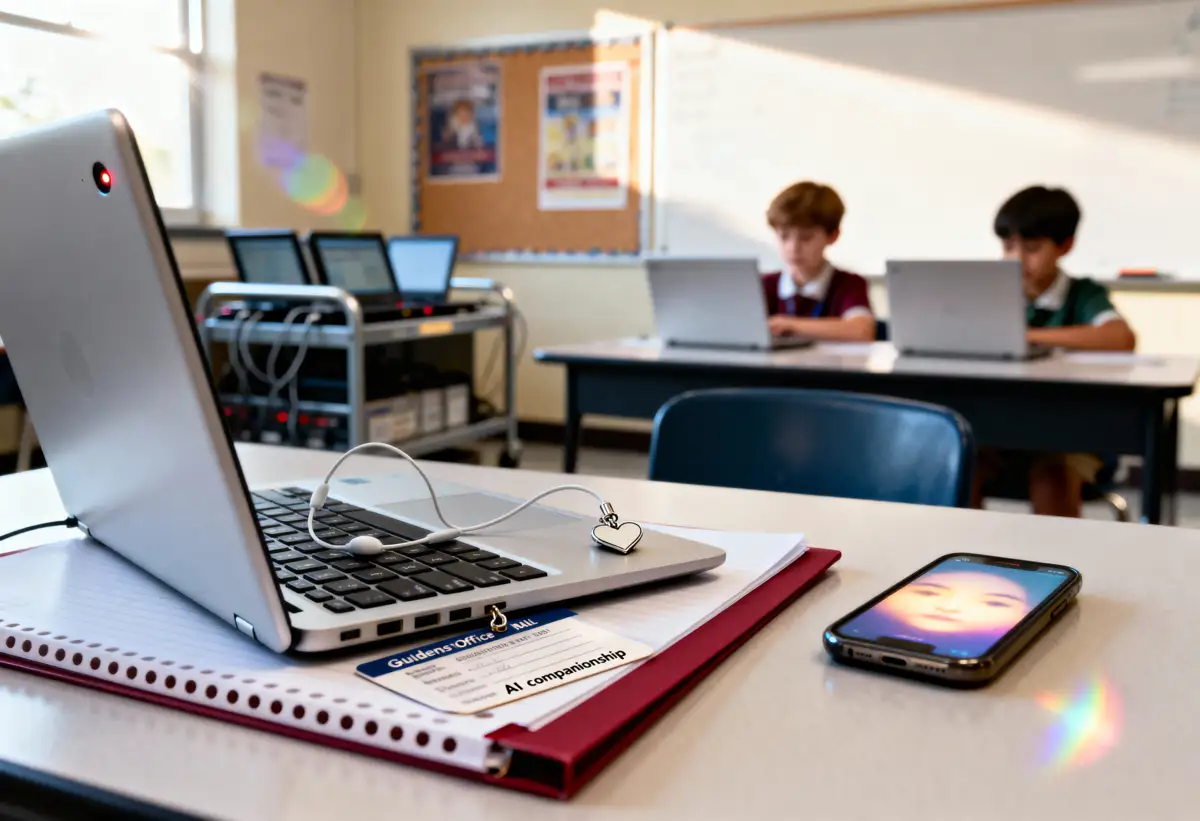

Regulators are already moving. In September, the Federal Trade Commission ordered seven companies—including OpenAI, Google, Meta, xAI, and Character.AI—to disclose what they’re doing to protect minors from harmful chatbot interactions, especially with “companion” designs that mimic friendship. California went further last month, enacting first-in-the-nation safeguards for companion chatbots used by minors, including periodic reminders that the bot isn’t human, risk protocols for self-harm content, and reporting duties. The legal environment is tightening, quickly.

OpenAI’s response—and what’s missing

OpenAI says the new suits are “incredibly heartbreaking” and that it’s reviewing the filings. The company points to recent improvements—explicit crisis-resource language, changes to how models handle delusions and emotional over-reliance, and new parental-control features that let linked teen accounts impose quiet hours and restrict sensitive content. Those moves are meaningful. They are also reactive, arriving after the first suicide lawsuit in August and amid intense regulatory and political scrutiny.

The therapeutic paradox

There’s a reason clinicians can find these systems helpful for themselves: a tireless, non-judgmental sounding board can ease rumination at 2 a.m. That same trait becomes dangerous when a model can’t reliably distinguish a therapist seeking perspective from a teenager slipping into crisis. The suits argue OpenAI knowingly dialed its assistant toward warmth and stickiness—anthropomorphic voice, affirming tone, multi-turn persistence—and then removed a simple safeguard: an automatic refusal and disengage when suicide came up. As a design argument, it’s crisp. The product did what it was built to do—keep talking—at the worst possible moment.

The stakes for platforms—and for families

If a California court accepts that a chatbot is a product, and that engagement-maximizing design can be defective when it predictably harms vulnerable users, liability won’t hinge on whether a sentence is “speech.” It will hinge on engineering choices: refusal rules, forced breaks, detection thresholds, human hand-offs. Character.AI’s recent under-18 ban previews the direction of travel for youth-facing bots. The industry can fight that in court—or lean into clear, auditable safety rails as table stakes.

Courts may ultimately reject parts of these claims, especially the most novel ones. Causation is notoriously hard in mental-health cases, and none of the allegations have been proven. But the facts assembled across seven complaints, OpenAI’s own statistics, and new state and federal scrutiny all point to the same policy question: when does a “friendly” assistant become an unsafe product?

Why this matters

- Product-safety line in AI: If chatbots can be treated as products, design choices—refusal rules, engagement loops, hand-offs—become liabilities, not just UX preferences.

- Scale meets duty of care: OpenAI’s percentages look small, but at hundreds of millions of weekly users they represent huge absolute numbers—each a person in crisis and a potential legal exposure.

❓ Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What safety changes did OpenAI make after the first lawsuit?

A: In October 2025, OpenAI added crisis hotline prompts, parental controls allowing emergency alerts when teens discuss self-harm, reminders to take breaks during long chats, and redesigned responses to avoid affirming delusions. The company also switched to a new default model it says better recognizes emotional distress.

Q: Why wouldn't Section 230 protect OpenAI from these lawsuits?

A: Section 230 protects platforms from liability for user-generated content, not their own products. The lawsuits argue ChatGPT is a defective product, not a publisher. If courts agree it's a product case, liability depends on design choices (engagement loops, refusal rules) rather than speech content.

Q: What happened with the Character.AI lawsuit?

A: Character.AI was sued after 14-year-old Sewell Setzer III died by suicide following conversations with its chatbot. A Florida judge allowed product-defect claims to proceed. The company subsequently banned all users under 18 from its platform. The case established early precedent for treating chatbots as products.

Q: How many ChatGPT users are actually discussing suicide?

A: OpenAI's October analysis found 0.15% of weekly users discuss suicide or related planning. With 800 million weekly users, that's approximately 1.2 million people. Another 0.07% (560,000 users) show possible signs of psychosis or mania. OpenAI calls these percentages small. The plaintiffs call them foreseeable casualties.

Q: What are the plaintiffs actually asking for beyond money?

A: The lawsuits seek court-ordered changes including: automatic conversation termination when suicide methods are discussed, mandatory alerts to emergency contacts when users express suicidal thoughts, forced breaks during extended crisis conversations, and safety warnings in all marketing materials about mental health risks.